Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

wai wai design explores an alternative cement for the UAE pavilion at Venice Biennale 2021

Wetland responds to the Venice Architecture Biennale's theme 'how will we live together?'

When Hashim Sarkis, Lebanese architect and curator of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale, called upon architects to question ‘how will we live together’, he prompted very timely responses that focus on global challenges. One such example comes from the UAE, where architects Wael Al Awar and Kenichi Teramoto are experimenting with an alternative cement for the country’s pavilion.

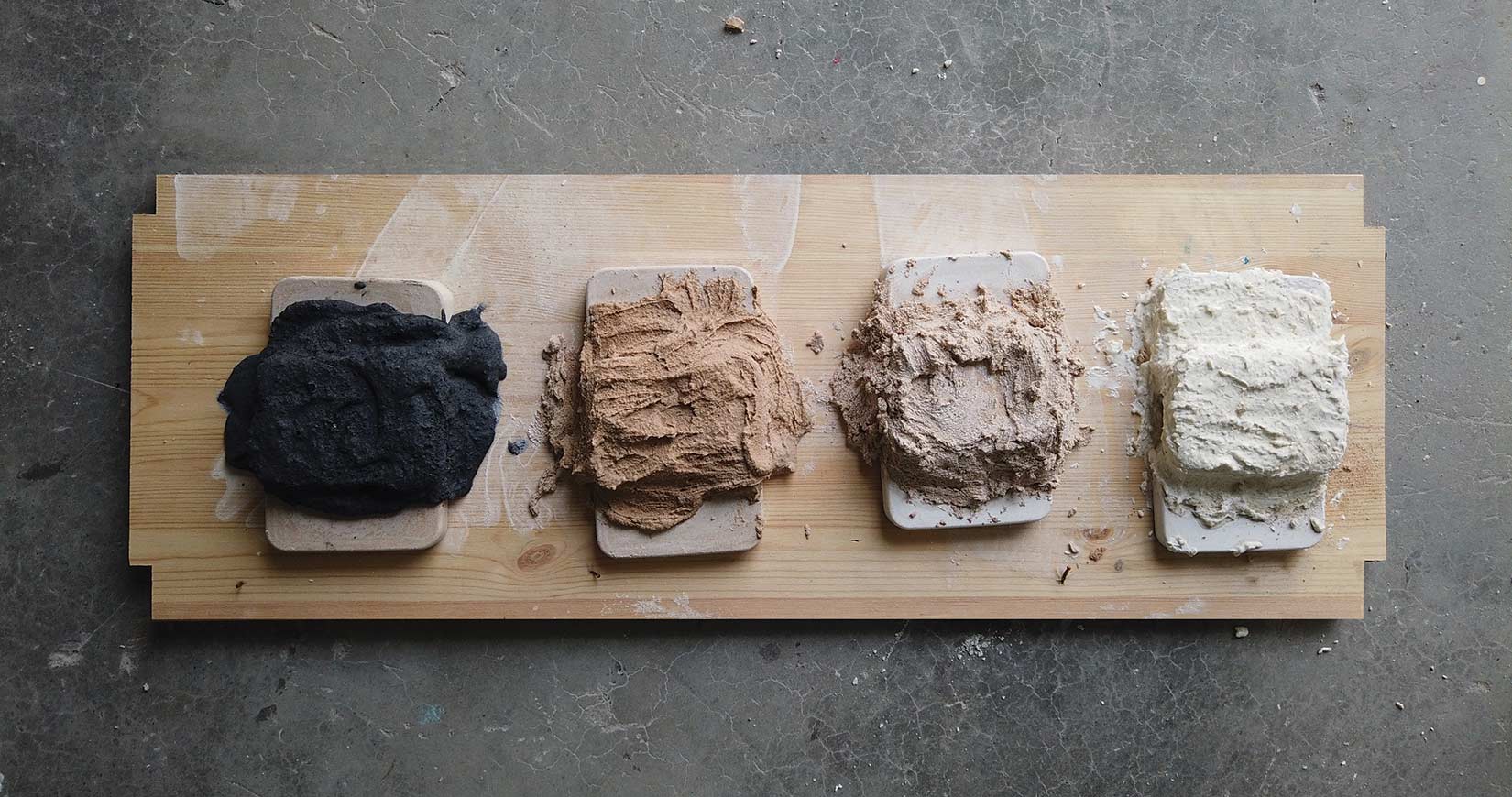

Founders of waiwai design, a multidisciplinary practice with offices in Dubai and Tokyo, Al Awar and Teramoto have long worked to address the social, environmental, economic and technological aspects of architectural projects, and their exhibition for the UAE’s pavilion, entitled Wetland, is no different. Confronting the harmful effects of traditional cement on the climate (cement generates eight percent of the world’s CO2 emissions), the curators will present a structural prototype inspired by the UAE’s sabkha (salt flats) and built from minerals extracted from the rejected brine of the country’s industrial desalination.

Kenichi Teramoto and Wael Al Awar. Image courtesy National Pavilion UAE La Biennale Di Venezia. Photography by Seeing Things.

“We were looking for a vernacular architecture that is similar to the region, and what we found was an architecture that used salt in the construction of buildings in Siwa, a region on the border of Egypt and Libya,” says Al Awar. “They extracted blocks from the sabkha itself and used mud as glue. That was interesting to us because the UAE’s landmass is five percent sabkha, or wetland.”

Although vernacular architecture in the UAE was typically crafted with coral, which Al Awar attributes to the material being easier to work with than the sabkha, the discovery of Siwa engendered a curiosity in the curators, and triggered a years-long research endeavour into building materials that could be made from locally available resources.

“To be clear, we have zero intention of using the sabkhas to build with,” says Al Awar. “They are simply a source of inspiration and something to learn from. In fact, we are fighting for their preservation because they are carbon sinks – one square metre of sabkha can absorb more CO2 than one square metre of rain forest. They are the lungs of the UAE.”

Al Awar and Teramoto – who are collaborating with several institutions and agencies including the environmental agency of Abu Dhabi, the American University of Sharjah, NYU Abu Dhabi and Tokyo University – have found a solution in the extracted minerals from the reject brine of desalinated water. With the UAE having the third-largest desalination plant on the planet (and en route to having the largest), there are plenty of resources to work with and meet the demands of the country’s development plans. According to Al Awar, the equivalent of nearly 5000 Olympic-sized swimming pools of rejected brine is dumped back into the sea on a daily basis once it’s been removed from the seawater during the purification process. This waste product can be recycled for construction, and the UAE’s pavilion will show just that, as the prototype will be built from 3000 units cast in soil and shaped like coral.

And while this is the basis of the pavilion’s exhibition, Wetland also aims to address several other ongoing challenges, including what Al Awar refers to as “issues caused by 20th-century individualism” and the modern architect’s neglect of greater responsibility. While both are dense topics to tackle, the pavilion’s team hopes that visitors pick up on its message of collaboration and each person’s responsibility to build a safer future.

“Hashim asked us how we will live together, and for us, we saw it as how will humans and nature live together,” says Al Awar. “We want people to really think about collaborating and talking to one another. We could not do what we have done without our partnerships. Through these collaborations, we can live together and develop a better future for ourselves. The 20th century was selfish – it was about the ‘me’, the ‘I’. But now it should be about the ‘we’. It should be about the communal.”

Read more: ‘Desert Cast: Towards an Identity’ uses architecture to explore local Kuwaiti identity

The Latest

Minotticucine Opens its First Luxury Kitchen Showroom in Dubai

The brand will showcase its novelties at the purity showroom in Dubai

Where Design Meets Experience

Fady Friberg has created a space that unites more than 70 brands under one roof, fostering community connection while delivering an experience unlike any other

Read ‘The Winner’s Issue’ – Note from the editor

Read the December issue now.

Art Dubai 2026 – What to Expect

The unveils new sections and global collaborations under new Director Dunja Gottweis.

‘One Nation’ Brings Art to Boxpark

A vibrant tribute to Emirati creativity.

In conversation with Karine Obegi and Mauro Nastri

We caught up with Karine Obegi, CEO of OBEGI Home and Mauro Nastri, Global Export Manager of Italian brand Porada, at their collaborative stand in Downtown Design.

The Edge of Calm

This home in Dubai Hills Estate balances sculptural minimalism with everyday ease

An interview with Huda Lighting at Downtown Design

During Downtown Design, we interviewed the team at Huda Lighting in addition to designers Tom Dixon and Lee Broom.

Downtown Design Returns to Riyadh in 2026

The fair will run its second edition at JAX District

Design Dialogues with KOHLER

We discussed the concept of 'Sustainable Futures' with Inge Moore of Muza Lab and Rakan Jandali at KCA International.

Design Dialogues with Ideal Standard x Villeroy & Boch

During Dubai Design Week 2025, identity held a panel at the Ideal Standard x Villeroy & Boch showroom in City Walk, on shaping experiences for hospitality.

A Touch of Luxury

Here’s how you can bring both sophistication and style to every room