Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Tosin Oshinowo reveals curatorial plans for the second Sharjah Architecture Triennial

The second edition of the Triennial will explore issues of scarcity across the Global South

Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo believes in a human-centric architecture. Her Lagos-based practice CmDesign Atelier is behind several residential and commercial projects in (and around) the city, such as the Maryland Mall (dubbed ‘The Big Black Box’ due to its frame and size), as well as apartment complexes and stylish beach houses. Her practice has also recently completed a rehousing project with the United Nations Development Programme in Northeast Nigeria’s Borno State, replacing the original Ngarannam village whose inhabitants had been displaced by insurgent group Boko Haram in 2015. The project includes 500 earthen-style homes arranged in a grid with shared facilities and was built in close consultation and communication with its community.

Tosin Oshinowo photographed by Bashar Belal

Many of Oshinowo’s endeavours follow these principles of human-centric design, whether it is about community engagement or giving voice to artists and creatives as part of her own projects (she has participated in several artistic projects herself, such as her collaboration with Lexus and London-based designer Chrissa Amuah). But besides being conscious of human efforts, Oshinowo is also keenly aware of the importance of one’s context, which has given way to an alternative view of sustainability: one that merits local materials and locally-appropriate architecture which strays from Western ‘modernisation’ and a ‘global style’. “[The architecture] needs to reference where it is from, it needs to be conscious of the environment and it needs to pull inspiration from its context,” she tells identity.

Oshinowo plans to carry forward these principles as part of her new role as the curator of the second edition of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, under the theme ‘The Beauty of Impermanence: An Architecture of Adaptability’, that will explore issues of scarcity across the Global South which has given rise to a culture of re-use, re-appropriation, innovation, collaboration and adaptation. “[The theme] comes from my understanding of my environment, my contextuality, and the fact that particularly in Africa, and in Lagos, we are always working with limited resources. [With this comes] an [abundance] of innovation and creativity. I used to think of it as a constraint, but to be honest, that is where we found our freedom.”

Al Qasimiya Private School is one of the venues for the Sharjah Architecture Triennial

Set to take place in November 2023, the Triennial will bring together architects, designers, planners, artists and product designers who are working towards reorienting global conversations to create a more inclusively sustainable and resilient future for people and the planet.

To prioritise sustainable practices that work with the climate rather than against it, Oshinowo asserts that one must “go back to go forward” and this calls for moving away from the canon of global notions of sustainability. “If I look at traditional buildings prior to colonialism, they were comfortable, they were appropriate, [and] there was a culture of maintenance, of renewal, of regeneration, which we have lost. We have this buzzword ‘sustainability’ today which [is] highly abused. It is not enough to have ‘zero impact’. The traditional buildings of the past were about the cycle of life and regenerating and renewing. [For example], in Northern Nigeria, at the end of every rainy season, there is a process of repairing the walls [of the building]. [It is] a natural cycle. We have lost so much of that in modern architecture,” she says.

The architect plans to tap practitioners from across the Global South who are working within the reality of scarcity, traditional technologies and adaptable design that are relevant to their contexts and could become learning examples for the rest of the world. While the detailed programming and participant list has not been fully defined, current plans include dividing the exhibition into a series of sections: one exploring architectures that adapt to their environment, one on innovative and contextual materials and another one the use of waste, that – although problematic – is being used to create interesting interventions.

“One of the biggest challenges we have, particularly in West Africa, is that we have become the dumping ground for the West’s clothes,” Oshinowo explains. This has affected local economies and is becoming an ecological issue as discarded textiles – and car parts – increase in the continent’s landfills. “The irony is that people do such interesting things with this waste.” While some of these waste products are recycled within their genre of use, other times they are readapted to create a whole new function. Car tyres, for example, play a big part in innovative furniture in Nigeria, with artists and designers giving discarded items a second life. Ugandan artist Bobby Kolade, for example, upcycles balls of second-hand clothing to create walls for houses.

The challenge here – and there are many – is convincing high-end clients that working with local materials and upcycling can produce comparable results to importing said materials from overseas, but Oshinowo is hopeful that with the right approach, the narrative can be changed. She cites Indian architect Vinu Daniel, founder of Wallmakers, who is building high-end residential projects using traditional techniques and eco-friendly materials such as clay. “It just goes to show that if architects and designers start to make a different way of seeing things attractive and aspirations, you would be surprised who will follow you down that road,” says Oshinowo. It is one thing to create this type of architecture because the planet requires it, but one must also make it attractive to a client, she adds. “We must be honest. Particularly as architects, we are providing a professional service that someone must pay for. We don’t have the luxury – as artists do – to produce work and that people then engage with. We are indirect salespeople, and we have to make it aspirational. And if we can do that then we are on the way to ensuring that these are the things that can become part of everyday life.”

To create an exhibition that is more diverse and gives voice to a larger pool of practitioners, Oshinowo has selected an advisory board of international architects who will help broaden the scope. I am very familiar with people within the African continent who are doing interesting work, but I was very aware that there was a limit to my knowledge of people who potentially could contribute to this theme from regions that I am not familiar with,” she says. It includes Hoor Al Qasimi, President of Sharjah Architecture Triennial and President & Director of Sharjah Art Foundation; Beatrice Galilee, co-Founder and executive director of The World Around; Mariam Kamara, founder of Atelier Masomi in Niger; Rahul Mehrotra, founder of RMA Architects of Mumbai British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare CBE RA; and Brazilian architect and urbanist Paulo Tavares.

I am very optimistic that, because of the advisory board, I’m really going to have a great, intense mix of people, that people haven’t seen [or may not know about],” says Oshinowo. The architect’s aim is to create an exhibition that is accessible to all and one that will hopefully make a future impact.

“I am not trying to answer any questions, but I am hoping that it will help us all think differently about how we approach our practices, how we approach climate change and have some type of long-term influence in how we generally do things,” she says. “The point is that we can inclusively look for solutions.”

Photography by Bashar Belal @basharbelal

The Latest

Innovation Meets Indulgence

Here are the latest launches for the bathroom that have caught our eye this year

A New Standard in Coastal Luxury

La Perla redefines seaside living with hand-crafted interiors and timeless architecture

Things to Covet

Here are some stunning, locally designed products that have caught our eye

An Urban Wadi

Designed by Dutch architects Mecanoo, this new museum’s design echoes natural rock formations

Studio 971 Relaunches Its Sheikh Zayed Showroom

The showroom reopens as a refined, contemporary destination celebrating Italian craftsmanship, innovation, and timeless design.

Making Space

This book reclaims the narrative of women in interior design

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

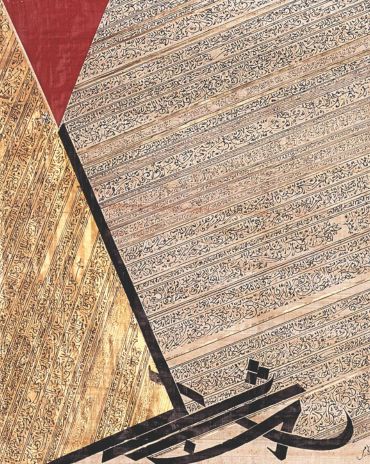

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.