Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Mariam Kamara on using architecture as a tool for ‘a higher purpose’

Read our interview with Nigerien architect Mariam Kamara, founder of atelier masomi

Mariam Kamara’s approach to architecture is vigorous, unapologetic, inquisitive and empowering. She is founder of architecture practice atelier masōmī, based in Niamey, and the studio’s many projects across her home country of Niger offer dignified spaces that benefit and serve local and regional communities. Whether it is a religious school and mosque or a monumental cultural centre, for Kamara, architecture and public space are a basic human right, and one that can be used to instil confidence, dismantle stereotypes and celebrate context, all while allowing people to dream bigger.

Can you start by telling us about your time growing up in Niger? How did it come to inform your work?

I think it has everything to do with my work. The most impactful time of my life, really, was growing up in the north of the country, in the middle of the Sahara Desert – and that is really what informed a lot of what I feel and think and practice in architecture. That is what made me so aware of the environment and my environment in particular, and climate – because it is obviously so much harsher than the climate in Niamey. But for me, living there and growing up there, and being confronted with the harsh climatic conditions, also went hand in hand with growing up in a place that had astonishingly old history and this is something that we are not taught at school anymore or are not necessarily made aware of – but the traces were everywhere. We had Neolithic carvings in the mountains nearby, there were towns from the early 15th century and the architecture was still there; people were still living in them, generations later. So, there was something that it gave me in terms of confidence in the identity that I had and the place I was from. It gave me this incredible luxury and certainty in the fact that we are not ‘less than’. Economic circumstances do not make who you are. African countries or other countries that are so-called ‘developing’ and that are categorised by their access to capital have nothing to do with your identity and your worth, and I was incredibly lucky that I grew up in an environment that instilled that in me since day one. Not because I read it somewhere or someone told me – but because I lived it, and it became unbelievably unshakeable and it made the work that I do today self-evident to myself. It was not something that I struggled to arrive at or something that seemed heroic to do or pursue, it was just natural – I cannot imagine practicing any other way.

Portrait of Mariam Kamara.

Can you talk about why public space plays such a vital role in your approach to architecture, and some aspects that you try to implement within your projects?

I think public space is important anywhere. I think turning into a more capitalistic society has made private ownership so key that public space has somewhat receded – but at the end of the day, it was always the life force of a place. It is about spaces where we come together and in the societies I have worked in the most, it is critical to local culture, maintaining a social fabric of solidarity, of neighbourliness which has all but vanished in the Western context and I find it alarming that we are so eager to rush in that direction as well. It is something that I always tried to give place to, even when I am creating a private project; I always try to have some ‘common’ components.

Hikma Religious and Secular Complex by Mariam Kamara and Yasaman Esmaili of Studio Chahar. Photography by James Wang.

The way much public space is designed now is usually conflated with projects with big budgets, but the smaller or ‘less economically viable’ areas become neglected from this narrative, so people are forced to then create their own sense of public space.

And this is what we should be looking at actually, these places that people create for themselves; they are the real sources of inspiration. We shouldn’t be so in love with the power of our own creativity, which [may feel] satisfying, but at end of the day, we are not supposed to make spaces that glorify ourselves. It is about what it’s doing for people who are using them, and I think unfortunately now, public space and public projects have become a lot more about how cities represent themselves and attract attention, which is also understandable and necessary, but it doesn’t have to be one or the other.

Dandaji Market. Photography by Maurice Ascani.

The fact that atelier masōmī conducts on-ground research is such a refreshing approach for an architecture practice today. Can you tell us more about how you go about this and how it informs your designs?

It doesn’t even have to take that long; you just have to be really prepared, know what you are looking for and develop a set of mechanisms to allow people to express themselves – but that’s what’s difficult. [That’s] because often people tell you what they think you want to hear, because they view you as a form of authority – [but] they are not the client who will tell you what they want but the users, who are not used to being empowered. So, we have developed a set of mechanisms depending on who we are talking to, whether they are young people or women or elders – there is a way of getting them to tell you what they really want without asking directly; it is a kind of art form that you have to develop.

Hikma Religious and Secular Complex.

What are some of the reactions you see when people finally experience the end results?

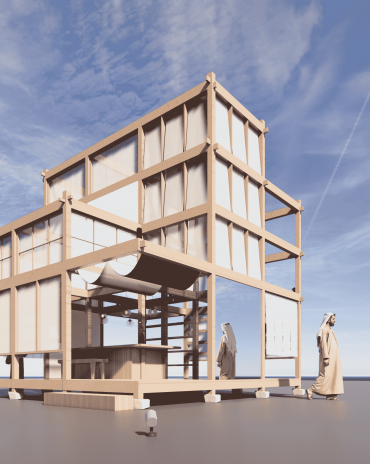

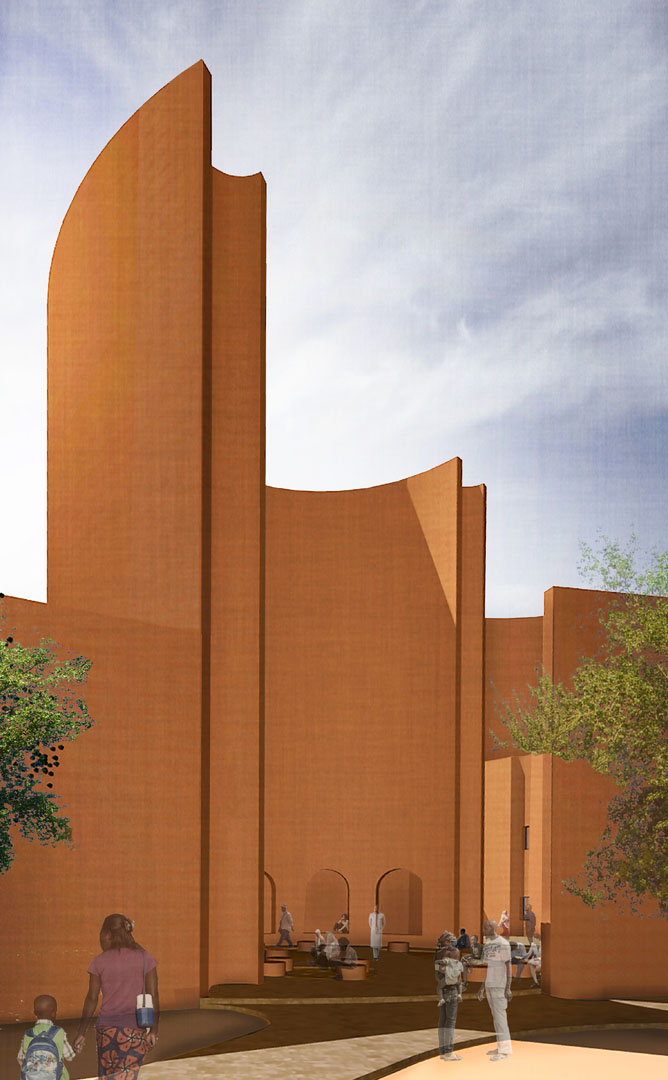

The project for which I received the strongest response was the Niamey Cultural Centre, which is not even built yet. For that one we had really close dealings with the future users, who were almost exclusively all teenagers. They were the first ones I showed the design to, before I showed it to anyone else. And their reaction really took me by surprise. Because, literally, this is the project for which I took everything they said and turned it into building form. They talked about nature, they talked about shade, they talked about tradition and identity – they were so incredibly smart.

We made a model of the project and they saw some 3D images, and one young man was staring at the model, and he said, “This is going to be here?” and I said, “Yeah, just a five-minute car ride from where we are”, and he asked again, “Here, in Niamey?” and I said, “Yeah”, and then he was quiet and another young lady asked, “When will it be ready? Because we need to go in there.” And there was something both endearing but also heart-breaking about that reaction. They had total disbelief; they were completely sceptical [thinking] that “No, this cannot be for us.” And that is the power of monuments – this is a very monumental project and often people like to say that ‘this is an African country, there are so many problems here, how can you build something like that?’, as if all we are only allowed to have are like, eight clinics, but others can have beautiful buildings.

Niamey Cultural Center – Aerial View ©ateliermasomi

But I could tell that they were scared to believe it and that was very heart-breaking for me because it really showed how little they thought they should expect and how little they thought they had a right to. That was the one that marked me the most. They were 16; how can you expect so little of the world at 16? If already you feel that ‘none of this can be for me’, that is awful.

Niamey Cultural Center.

But I think it is quite amazing that you are countering that perspective and showing people that no, a building like this does belong here and it is for the people to use.

Exactly – and that is incredibly important to me. Even though I don’t speak about aesthetics a lot, I pour a lot of aesthetic intent into all [my] projects. I want to make sure that it comes from the local know-how and the local skills, so it is also something that you recognise. But then we always try to find ways to elevate it and contemporarise it, and serve it back because, again, we are so used to ‘seeing’ that anything that is monumental or that looks amazing should only have a Western aesthetic. And for me, when I started working, I already knew that there was no truth in that. So, what I was really excited about when I started practicing architecture was to create world-class level architecture – but [architecture] that looked just like us. Which, in a way, makes practice incredibly difficult but also exciting because we do not have access to all the technologies, so we try to create that perfection through artisanal means, which is completely counter to what you would imagine but – I think – is also what gives it its soul.

The library at the Niamey Cultural Center.

And the Niamey Cultural Centre is the one you worked on with David Adjaye?

Yes, he guided me as I was designing it – it was more of a mentorship. It was like having someone whose utter mastery you trust, and them helping you actually transcend whatever level you are at. I had never done something so monumental before and even when I looked back at my initial sketches and models, they were just so much more polite.

Yes, so you also needed that push.

Yeah, and it was still a departure from what I usually did – I thought I was pushing the envelope, but it was really about having someone you could talk to who would look at what you are doing and say ‘no, you can push this way further, don’t be afraid – let it soar’. It is also about talking to someone who gives you licence. Coming from the context that I come from, your ego is always in check because you are always being told you are ‘not as good as’, and even when you think you are pushing yourself, you actually are not. And from that point of view, I’m not any different from those children I was talking about. The reality is, I didn’t imagine it in [the] beginning myself, not to that level. What I imagined was not as audacious.

Performance space at the Niamey Cultural Center.

How would you say your work in architecture counters the impact of colonisation on Niger’s built environment?

The irony of colonisation is that you only freed yourself so that you can follow in the footsteps of your previous masters. Because it is either that or you don’t really exist in the world, and all of us found ourselves in that trap that there was no way out of. I think a lot about how we could have done it differently, because they leave and you have freedom but they have already put in place institutions and they already put in place a capitalistic economy and governments – and I am trying to figure out why is it that we didn’t go back to the way we used to be; but that is not possible, because you have been forever changed.

Artisans Valley. ©ateliermaomi

And that is what I am confronting in my work. I am not trying to go back 100 years – in a way that is pointless because we have already been forever changed. So, what I am doing is to completely ignore what they did and ask myself, “Who are we now? What are we?” and I design for that. And [I ask] “What do we want to be?” and I design for that. [Because] now you get to mould your own image, and that is what we failed to do before, because we tried to mould ourselves to show that we are good students rather than thinking about all the wonderful things that we are and how amazing we could be. And for me, [that’s] what’s really exciting and why I will be practicing architecture probably until I am on my deathbed, because architecture is just a tool for me. As much as I love it because I am a creative, I am also putting it in the service of a higher purpose.

The Latest

The Art of the Outdoors

The Edra Standard Outdoor sofa redefines outdoor living through design that feels, connects and endures

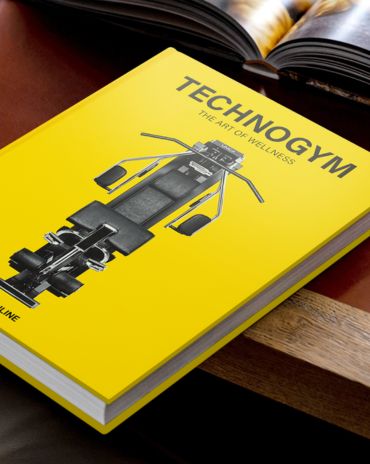

The Art of Wellness

Technogym collaborates with Assouline to release a book that celebrates the brand’s 30-year contribution to the fitness industry

The Destination for Inspired Living – Modora Home

Five reasons why you need to visit the latest homegrown addition to the UAE’s interiors landscape

Elemental Balance — A Story Told Through Surfaces

This year at Downtown Design 2025, ClayArk invites visitors to step into a world where design finds its rhythm in nature’s quiet harmony.

The identity Insider’s Guide to Downtown Design 2025

With the fair around the corner, here’s an exciting guide for the debuts and exhibits that you shouldn’t miss

A Striking Entrance

The Oikos Synua door with its backlit onyx finish makes a great impression at this home in Kuwait.

Marvel T – The latest launch by Atlas Concorde

Atlas Concorde launches Marvel T, a new interpretation of travertine in collaboration with HBA.

Read ‘Regional Excellence’ – Note from the editor

Read the magazine on issuu or grab it off newsstands now.

Chatai: Where Tradition Meets Contemporary Calm

Inspired by Japanese tea rooms and street stalls, the space invites pause, dialogue, and cultural reflection in the heart of Dubai Design District

A Floating Vision: Dubai Museum of Art Rises from the Creek

Inspired by the sea and pearls, the Dubai Museum of Art becomes a floating ode to the city’s heritage and its boundless artistic ambition.

Heritage Reimagined

Designlab Experience turns iconic spaces into living narratives of Emirati culture, luxury, and craftsmanship.

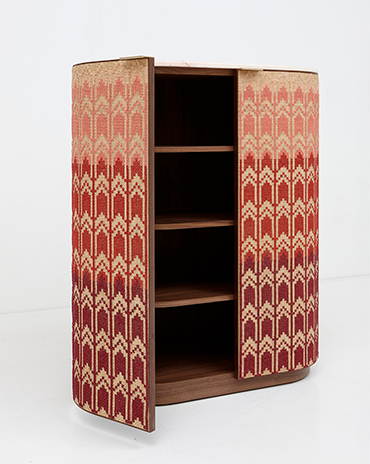

Nakhla by Nada Debs

Nakhla symbolises resilience, prosperity and a deep connection to the land