Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Ibbki’s ceramic designs pay homage to craft traditions of Algeria’s Kabylia region

The designs are inspired by real-life experiences as well as ancestral symbology

Located in northern Algeria, the Kabylia region forms part of the Tell Atlas mountain range and is set just at the edge of the Mediterranean Sea. The region was historically part of Numidia, an ancient Berber kingdom located in the northwest of Africa in modern-day Algeria that later expanded across what is now Tunisia, Libya and some parts of Morocco.

It is this mountainous region that influenced Azel Ait-Mokhtar and Youri Asantcheeff to start their design brand, Ibkki, collaborating with local Algerian craftsmen to create objects inspired by the culture, people and craft traditions of Kabylia. The founders, who themselves were already working with handcrafts in Paris (Ait-Mokhtar worked with wood, Asantcheeff on metal) found common ground with Ibkki.

Ait-Mokhtar’s ancestral ties connected the brand even further to the region. His family are Imazighen (Berber) people from Kabylia, who have had a long history in the region, where craft was an integral part of society. While he continued to visit his ancestral home where his family still resides, on one of his trips he invited Asantcheeff to join him (the two had met during university in Paris while studying industrial design). A friend of Ait-Mokhtar’s father introduced them to craftsmen around the area, one of whom the duo formed a strong connection with.

“At this point it was pure discovery,” Asantcheeff recalls. “When we came back to Paris, we thought it would be interesting to push these meetings further as we are both very much into hand-crafting; it felt like a natural [next step]. We decided to go back and see what we could do.”

Today, Ibkki works primarily with ceramics: vases, plates and bowls. Pottery is an important tradition among Berber people in Kabylia, where it was practiced primarily by women for functional needs such as carrying water and conserving, serving or preparing meals. It was also used for ritualistic purposes, integrating various geometric symbols that served both a decorative function, helping to pass on stories and various teachings, and one of communication among various villages and families, especially during the time of French colonisation. “My grandmother did some pottery as well,” Ait-Mokhtar shares. “It is something that is very deeply linked to the culture.”

While Ibkki’s own designs are inspired by these symbols, the duo researched meanings across libraries in the country’s capital, Algiers; they then experimented with their own interpretations of geometric patterns and forms, which developed into a language or ‘alphabet’ of their own.

“When we began, we set a rule that we wouldn’t use traditional archetypes of the region so as not to appropriate what already exists,” Ait-Mokhtar explains. “What we wanted to do was use the ancestral way of making ceramics by studying it and learning from the craftspeople, and from there create something completely new. This is why one of our main inspirations is the actual feeling of living there. We tried to take in as much as we could from our life there, everything we have experienced, and to translate it into object form, and I think that’s how the separation between ancestral craft and contemporary design was formed.”

Nabil, the craftsman the duo met and formed a close relationship with – and who primarily produces their objects – also influenced their material choice. “Nabil is very young, so he is open to challenges and from there we were able to gain a lot of freedom in our work. Ceramics is [a] very rewarding [medium] to work with; you are literally giving shape to your ideas, but it is also very technical, so we had to do a lot of research while also bringing some of the knowledge that we gained in France. I think it was the best material to start our journey and give body to this new language,” Ait-Mokhtar adds.

Ait-Mokhtar and Asantcheeff treat their time in the workshops as one would with a residency: learning, perfecting and collaborating directly with craftspeople. It is a hands-on approach and the preferred way of working for the duo. However, the area of the making process where they have taken full ownership is the glazing, which they feel lends the most freedom for creative expression and experimentation. “For example, we use glazes that don’t ‘like’ each other; ones that don’t like to move with one that moves a lot – and we try to see how it works. Sometimes we fire the pieces several times – also something that we aren’t ‘supposed’ to do. We also like to mix glazes from Algeria with ones from Paris. I think that is also a cool parallel that we are able to create with our projects: they mix together even though they are not from the same place,” Ait-Mokhtar shares.

The duo is conscious of the volatile nature of traditional crafts in Algeria, which are slowly disappearing as the younger population look for better-paid work. It is a difficult and time-consuming endeavour to create something that will actually sell, the designers explain. Many of the craftsmen rely on international brands who commission big orders, or trinkets for tourists which do not allow for the practice or preservation of their traditions. “I wouldn’t say we are trying to find a solution to the problem, since we are not a large practice, but we wanted to find an alternative way of working that would preserve the crafts and allow the craftsmen to earn money and to work freely and perpetrate their traditions,” Ait-Mokhtar explains.

And while the craftsmen help bring Ibkki’s designs to life, the designers in return help them with finding solutions for how to sell their products. “We do not do this for money, but because we want to help them, and it is a small part of the exchange and the dialogue between us, because we now feel part of the family,” Asantcheeff adds.

The duo has an office in Paris and spends between five to eight months in a year developing their collections in Kabylia, as well as taking orders for various retailers and private clients. Each of the pieces are unique and created in clusters of ten per model.

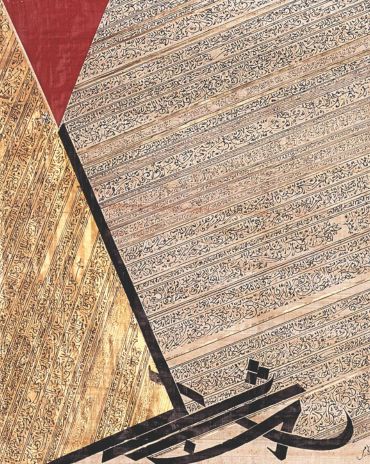

Recently, Ibkki has collaborated with French brand Maison Château Rouge on a new ceramic collection of four vases, part of a larger project that pairs designers with artisans from across Africa – spanning Mali, Madagascar, Togo and Tunisia, among others. They have also created their first rug, AMENZU (revealed exclusively through identity) for the Parisian gallery Chevalier & Parsua, which has been working with Iranian craftsmen since 2001. The rugs are all made in Iran using traditional techniques and natural dyes.

“It was our first time working on a two-dimensional piece, but we accepted the challenge as the gallery has the same ideals in shedding light on the knowledge of craftsmanship within a contemporary setting,” the duo explains. They designed the rug while in Kabylia, working on their second collection of ceramics. It is no surprise then, that AMENZU is a dynamic translation of the feeling of being in the mountains, expressed through a reinterpretation of the geometric alphabet found across Kabylian pottery.

“In the future, we [want to] experiment with different materials,” the designers reveal, “but [still] keep to the same model of working and learning from craftsmen while creating dialogue between cultures.”

The Latest

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.