Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Generation design: Keiji Takeuchi

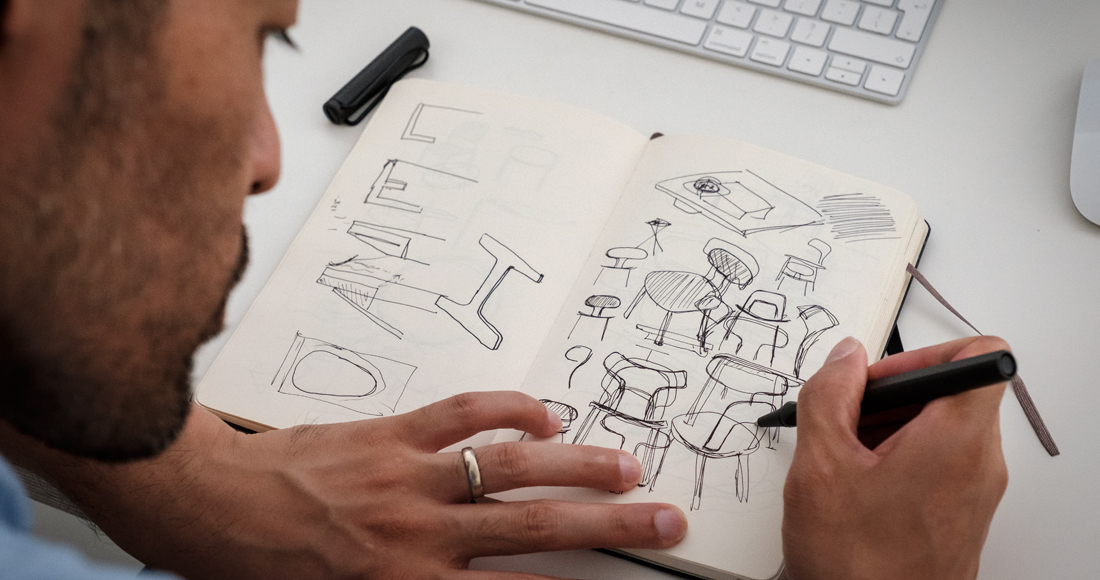

Our id Design Awards juror answers the same questions posed to Charles + Ray Eames.

We were ecstatic when Takeuchi joined Head Juror Marco Piva for our id Design Awards this past 14 October. And to celebrate this presence in the region, he was honoured by id Design Awards sponsors Herman Miller and Jalapeño Trading to present his new collection at the Herman Miller Regional Design Centre in Dubai.

Keiji during a visit to the Herman Miller Regional Design Office in Dubai Marina.

Because of the incredible level of interest in Keiji’s work as a designer, we’ve revisited an interview from Herman Miller’s WHY Magazine (for whom he has designed a number of products through Geiger). Here, he submits to the questions Charles and Ray Eames famously answered in their 1972 film Design Q & A. Read on for a glimpse of Keiji Takeuchi’s work, life, and how he imagines design can improve lives.

Keiji Takeuchi is an internationalist. He was born in Japan, decamped for New Zealand as a teenager, studied design in Paris, worked alongside legendary minimalist Naoto Fukasawa in Tokyo, and now runs his own studio in Milan.

His global outlook enables him to develop products—like Leeway Seating and the Axon Table, designed with Fukasawa, both for Geiger—that transcend language and culture to address fundamental concerns. His trick: marry a close observation of human behaviour to essential forms. The result is an oeuvre of furniture and lighting designs with intrinsic functionality and rejection of the superfluous still embraces the need for pleasure.

What is your definition of design?

The act of interpreting things and phenomena around us; the ability to notice something that is not quite working well to your eyes and take the opportunity to transform it to something positive; and the drive to give an answer or solution.

Is design an expression of art?

For me, art is not a thing—it is a phenomenon that rises in us. That’s not the objective for design, but design has to have a certain artistic sensibility; otherwise, it is not quite alive in a way. That is the value people seek in design.

Is design a craft for industrial purposes?

It can be. Design is a process of making layers and layers of decisions and trying to combine all the decisions you make together into one thing. There are infinite possibilities to the ways we deal with things, and design is about trying to find the right answer for every single constraint and connecting all the optimum decisions together.

What are the boundaries of design?

There aren’t any, because design is not a thing, it’s a phenomenon. Many people think design is about making something physical or visible, but I think it is more about emotional values. Sometimes you don’t need physical things to make you smile.

Keiji Takeuchi (far right) works closely with the other members of his Milan studio in a system that mirrors his own relationship with his mentor and collaborator Naoto Fukasawa.

Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

I don’t think so. Design itself is an idea that exists in everyone’s mind, to interpret things positively. It is integrated into the whole environment.

Is it a method of general expression?

The execution of design needs highly sophisticated skills and beliefs, but what to expose and how to express that depends on the individual, because you are trying to share a point of view.

Is design a creation of an individual?

No, you can never be just ‘yourself’. One colour cannot exist without any other colours. You can’t be ‘white’ if there’s no other colours around.

Is design a creation of a group?

Not necessarily a set group, but common beliefs set our norms and directions. And there are users at the end of the process. So yes, it’s plural, not singular.

[row][column width=”50%”]

[/column][column width=”50%”]

In the evenings, Takeuchi heads down to a local park to play petanque with group of Italian gentlemen.

[/column][/row]

Is there a design ethic?

Yes, I think it’s moral. Designers have a huge social responsibility and it is not just about doing what they want to satisfy themselves. I hope that the ideas they introduce are to improve our quality of life.

Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

As a starting point it should be, but what is function? Things that make people happy without reason are also very important in our life.

Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

I would be happy if I could create a universal pleasure through my work. I think this is a set goal for designers after all.

Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

From analysing things, you can come up with a basic logic to start the design process, but logic itself does not give life to things.

Can the computer substitute for the designer?

That’s the same as asking, ‘Can cookware substitute for the chef’? You need them both. In terms of operation, computers are an extremely powerful support to have and there are many things they can do better than us. But they cannot replace intuition and our random imaginations and hunches. We both have to work together.

[row][column width=”50%”]

[/column][column width=”50%”]

If instilling a sense of happiness is part of Takeuchi’s design ethos, he lives it over lunch at a local Sicilian restaurant with his team.

[/column][/row]

Does design imply industrial manufacture?

Yes and no, because sometimes we ask simple questions that push the boundaries of industry.

Is design modifying an old object through new techniques?

It is about improving and adjusting things to fit with our fast-changing world. It’s refining, and that’s called culture.

Is design fixing up an existing model so that it is more attractive?

What is attractive? Fixing things does not necessarily make things more attractive. Sometimes it can make them less charming.

Is design an element of industrial policy?

I think someone designed the policy.

Does design admit constraint?

Yes, but constraints are not necessarily negative. We just need to learn how to transform them to a positive factor.

The Leeway chair that Takeuchi designed for Geiger, shown here in a black urethane, walnut, and ash seat and back combinations, comes with either a wood or metal frame.

What constraints?

All sorts of constraints. There’s physical constraints, moral constraints, emotional constraints, financial constraints—it’s the ecosystem of the whole world. But as I said above, we just need to find a way to be friends with them.

Should design obey laws?

If the law is about improving the quality of living, like social welfare, social support, and so on, then yes. It comes back to morals (if law is based on morals), because the purpose of design is to improve our life quality and make people happy.

What are your thoughts about schools of design?

The cycle is getting faster and faster as we are so connected. You see one school is trying to be original, other people just keep repeating, and typically, the school that has the principle does not really get affected by the tendency—they remain strongly themselves.

Is design ephemeral?

Yes and no. Good designs live long but are not necessarily appreciated in the same way throughout their life cycle; their value transforms throughout time. That’s not only because the design is good or bad, but technology is changing, and our lives are changing.

Ought design tend towards the ephemeral or toward permanence?

I think there is a difference between permanence and timelessness. To me timelessness is something that is alive throughout time. If so, it is a wonderful goal for design, I imagine. But at the same time, ephemerality has its own quality expressing the volatility of life. Without that, timelessness can be meaningless.

This walnut Leeway chair for Geiger shows off the company’s commitment to woodcraft, particularly in the finger joint of the gently arcing chair back.

Do you define yourself as a decorator? An interior architect? A stylist?

None of them. I am much more interested in thinking about how I can purposefully do things to improve our quality of life. I would like to answer a question of principle, whatever it is. I don’t want to just do things without questioning the purpose.

To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

To the human soul, not to any class of people. It has to be for everyone but definitely not only for the high end. I am against design that is more expensive than people can afford; that’s not the right way for me.

Do you feel you have been able to ‘design’ under satisfactory conditions, or even optimum conditions?

No. I think I am happily not satisfied with the conditions and this curiosity generates energy to continue my life as a designer. It’s a never-ending story I guess.

Takeuchi spent seven years working in Naoto Fukasawa’s Tokyo studio before his interest in furniture design took him to Italy to open Fukasawa’s Milan office. Today, he runs (and hangs out on the landing of) his own Milan studio.

Have you been forced to accept compromises?

Yes, but I always try to come up with a positive interpretation of every situation. That’s creativity, and it’s how designers survive: we need to adapt to things with positive thinking. A designer has to be a bit of a freak to go out and find problems. Once you solve that problem, you find the next one. It’s happy never ending. Problems are a living thing, and because we are living and changing the way we live, our problems change at the same time.

What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

Curiosity and optimistic thinking. Understanding what makes people feel good.

What is the future of design?

The distance between ‘design’ and the general public is closing. People are realising that design is not necessarily about objects, but about improving our thinking process and values. That’s why we often hear the term ‘design thinking’. In terms of traditional design and craftsmanship, execution is changing from hardware to software or to an integration between the two, but the mind-set is always the same. The thinking is there, but the canvas is different.

We would like to extend a huge thank you to Herman Miller who extended this interview written by Luke Baker to id. It was first published in their renowned WHY magazine and has been edited for identity.ae.

Photography: Ben Anders

The Latest

Designing Movement

RIMOWA’s signature grooved aluminium meets Vitra’s refined design sensibilities

A Sense of Sanctuary

We interview Tanuj Goenka, Director of Kerry Hill Architects (KHA) on the development of the latest Aman Residences in Dubai

Elevated Design

In the heart of Saudi Arabia’s Aseer region, DLR Group has redefined hospitality through bold architecture, regional resonance and a contemporary lens on culture at Hilton The Point

Turkish furniture house BYKEPI opens its first flagship in Dubai

Located in the Art of Living, the new BYKEPI store adds to the brand's international expansion.

Yla launches Audace – where metal transforms into sculptural elegance

The UAE-based luxury furniture atelier reimagines the role of metal in interior design through its inaugural collection.

Step inside Al Huzaifa Design Studio’s latest project

The studio has announced the completion of a bespoke holiday villa project in Fujairah.

Soulful Sanctuary

We take you inside a British design duo’s Tulum vacation home

A Sculptural Ode to the Sea

Designed by Killa Design, this bold architectural statement captures the spirit of superyachts and sustainability, and the evolution of Dubai’s coastline

Elevate Your Reading Space

Assouline’s new objects and home fragrances collection are an ideal complement to your reading rituals

All Aboard

What it will be like aboard the world’s largest residential yacht, the ULYSSIA?

Inside The Charleston

A tribute to Galle Fort’s complex heritage, The Charleston blends Art Deco elegance with Sri Lankan artistry and Bawa-infused modernism

Design Take: Buddha Bar

We unveil the story behind the iconic design of the much-loved Buddha Bar in Grosvenor House.