Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Design duo soft-geometry are reinterpreting traditional Indian craft through the lens of ‘softness’

The Indian designers create whimsical objects reminiscent of their childhoods

Utharaa Zacharias and Palaash Chaudhary are the duo behind soft-geometry, a design studio based between California and Kochi, India. The duo is creating artful furniture and home objects that are full of quirks and humour, driven by traditional Indian craftsmanship that’s reminiscent of their childhoods.

What inspired you to start soft-geometry?

Utharaa Zacharias (UZ): Each other. Our working relationship, that was centred around design and later friendship, was the foundation for our experiments. We tried to understand what made our collaboration work, who we are together and what we wanted to be doing. The dialogue and process was always interesting, and soft-geometry was born as a medium for this continued exploration between us as partners – a medium [that’s] reflective of our intricate, unique quirks and evolving philosophies.

How would you describe the pieces you create?

UZ: Everything we design is expressive of us and ‘soft’ is how we would describe us – our personalities – if that makes sense. As an extension of that, ‘soft’ is what we aspire to in our products, our work, and everything we touch. We think of ‘softness’ as slowness, intimacy, humour, humility, kindness and a quiet sort of courage and strength to be different and true, even if it is sometimes awkward or strange. It may be hard to view all of this in objects, but the hope is that you still feel it, a softness within geometries, hence the name.

How does the context of India influence your design language?

Palaash Chaudhary (PC): Growing up in India, craft and craftsmanship were all around us. Some of the most utilitarian objects in an Indian home are hand-made – step stools in bamboo with a distinct colour pattern, block-printed bedding, hammered brass lottas, hand-carved wood boxes, handloom cotton clothes and endless terracotta pottery. Granted, they barely ever matched, didn’t belong to a style or palette, and were not ever modular or stackable or ‘easy to clean’, but they worked – they were beautiful and they carried stories.

We try to carry that idea forward in our work: objects that reflect the process, materials, craft, story and ideas behind them. In other words, our Indian heritage makes us strive for objects that are more than just objects; objects that are poetic.

How did you begin working with craftspeople in India?

UZ: When we started soft-geometry we knew we wanted to slowly learn of our favourite Indian crafts [and] their context and history, practice their skills and techniques and fully understand and appreciate them, if and before we interpret them in our own work.

One of the first crafts we learnt and now hand-make by ourselves is the hand-woven cane side table, using the six-step tie technique abundant in India. We learnt first-hand from women artisans who practice weaving cane baskets, stools, chairs and the like at extraordinary speeds, every day, in clusters in Kerala. To commit to doing the cane tops for our tables in-house and by ourselves is something we take immense pride in, as it reinforces the importance of carrying this knowledge forward in modern design, which has a lot to learn from craft.

Tell us about some of your key pieces.

PC: The Donut Coffee Table was really special to work on. The project was centred around a sustainable use for wood waste. It was challenging, collaborative and quite tricky to solve – all of which made an exciting brief!

It started when an export furniture factory from India reached out to us regarding their solid wood cut-offs. Primarily supplying furniture to American retailers, they have to follow a stringent selection process for wood boards. Any board that carries knots or unusual grain patterns has to be rejected. This process of elimination accumulates vast quantities of wood cut-offs that are now waste. Both of us, like many Indians, grew up within strict instructions to never waste anything – not a grain of rice nor the last inch of a pencil. We can still hear our parents’ voices saying exactly those things and that became the context for the brief.

We worked closely with the factory on studying and categorising all of the different sizes of wood cut-offs. What was both beautiful and challenging was that there was little uniformity between them. We decided the piece needed to be sculptural, something that can take on these different sizes and celebrate them instead of discarding their ‘flaws’, and thus we arrived at the ‘Donut’.

The seemingly simple form of the ‘Donut’ and its circular cross-section allowed us to design a system of arranging the wood boards that made all these weird sizes come together, and then could be carved on a CNC machine. The process of arranging the boards is on a grid format but the final form is rounded (we cannot pre-guess the wood grain), so we are only able to see the grain after the piece comes out of the CNC – which makes every piece unique and allows little room for waste. Any piece that came off the carving can again be used in the next ‘Donut’. It was very satisfying to arrive at an object that is so beautiful and very ‘us’, using waste material.

What are some changes that you would like to see within the furniture industry?

UZ: We exist in the tiny fringe of ‘collectible’ design within the larger furniture industry. Within the bubble of that space, one of the more encouraging things we have seen is a small start to being more inclusive of aesthetics that are different from just Euro-centric modern design. It’s getting more expressive, louder, more fun and there are more diverse voices. It’s long overdue and we hope that continues.

What we’d love to see change in the larger furniture industry is mass retailers and the like to start crediting small design practices for the ideas that they quite shamelessly rip off year after year, and pump into the market. Why is it okay for mass-market retailers to visit design weeks every year, see original designs from small studios, take photographs of details and send it to their suppliers to recreate? There is an argument to be made for high-end design trickling into the mass market; however, larger companies have the clout and resources to either collaborate with the small studio/designer or at the very least credit them when they use their work as ‘inspiration’.

What’s in the pipeline for soft-geometry?

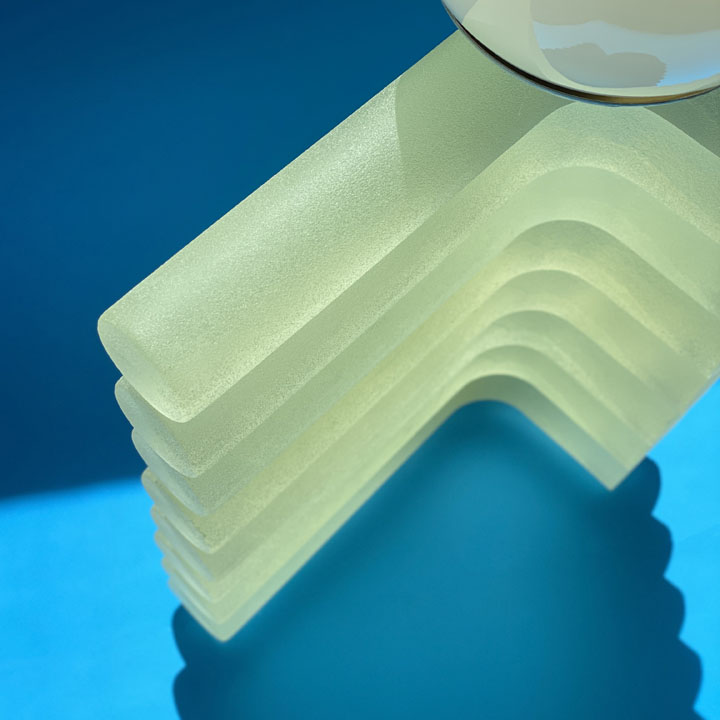

PC: Last year, somehow, even with the chaos of the lockdowns, we made an exciting foray into a new material, texture and story with the Elio lamps. We’ll be thinking of exploring the depth of that idea more and expanding the series. We also have little ‘minion’ projects at the experimental stage right now: some glass, some inlay crafts, some castings and so on. Usually, as we work through them, the fog clears and there are one or two that emerge as compelling and we steer that way. It’s still too early to tell!

Read more: Rana Begum shares her journey as an artist and gaining confidence in her craft

The Latest

Inside The Charleston

A tribute to Galle Fort’s complex heritage, The Charleston blends Art Deco elegance with Sri Lankan artistry and Bawa-infused modernism

Design Take: Buddha Bar

We unveil the story behind the iconic design of the much-loved Buddha Bar in Grosvenor House.

A Layered Narrative

An Edwardian home in London becomes a serene gallery of culture, craft and contemporary design

A Brand Symphony

Kader Mithani, CEO of Casamia, and Gian Luca Gessi, CEO of Gessi, reflect on the partnership between the two brands

The Art of Wellness

Kintsugi in Abu Dhabi, situated in a seven-storey villa, offers the ultimate zen retreat

Design Take: Inside the Royal Suite at Jumeirah Al Naseem

With sweeping views of the ocean and Burj Al Arab, this two bedroom royal suite offers a lush stay.

Elevated Living

Designed by La Bottega Interiors, this penthouse at the Delano Dubai echoes soft minimalism

Quiet Luxury

Studio SuCo transforms a villa in Dubailand into a refined home

Contrasting Textures

Located in Al Barari and designed by BONE Studio, this home provides both openness and intimacy through the unique use of materials

Stillness, Form and Function

Yasmin Farahmandy of Y Design Interior has designed a home for a creative from the film industry

From Private to Public

How ELE Interior is reshaping hospitality and commercial spaces around the world – while staying unmistakably itself

A collaborative design journey

A Life By Design (ALBD) Group and Condor Developers have collaborated on some standout spaces in Dubai