Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Asif Khan reveals the story behind Expo 2020 Dubai’s public realm

Khan has designed the public realm as an open-air pavilion

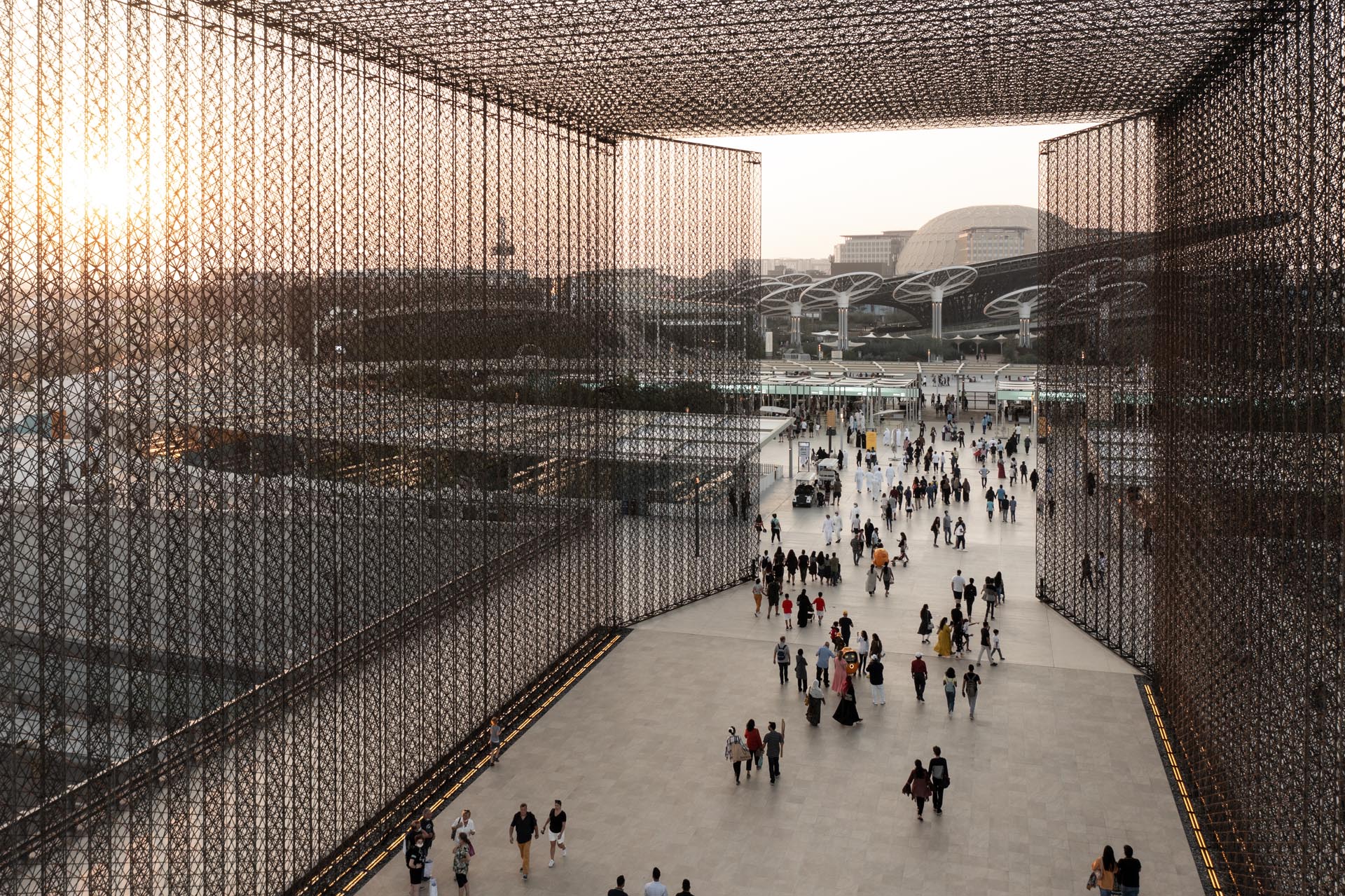

While many are familiar with British architect Asif Khan’s work on the magnificent carbon fibre gates that welcome visitors to Expo 2020 Dubai, his design scope in fact spans the wider public realm of the overall site: an open-air pavilion in its own right.

Khan first entered the project through a competition bid to design the Mobility Pavilion (which eventually went to Foster + Partners); however, a year later the architect returned to drive the design concept for the public areas of the overall site. “My interpretation was to bring scale, emotion and human senses to the public realm,” Khan tells identity.

A focus on the sense of arrival to the site, and the navigation that follows, led to the idea of sequences that reference traditional Arab cities, building on the relationship between a gateway, a courtyard and ‘the medina’ (the overall Expo site). “Our work was to help visitors navigate intuitively, while also creating a design which was born from ideas present in this region,” Khan says. Creating a variety of structural scales was vital to this concept of navigation, with visitors starting their journey at the drop-off area, then walking past (or through) the flags, entering through the portals to the arrivals and finally reaching the welcome plaza. The architect’s work additionally spans everything from the walking tracks and the landscaping, seating and lighting to a floating observation garden.

No doubt the entry portals are the most monumental of Khan’s contributions to Dubai’s Expo site and are evocative of the many architectural and engineering innovations launched across World Expos historically – from Joseph Paxton’s glass and iron Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 to Gustave Eiffel’s skeletal tower designed for Paris in 1889, which has become a symbol of the city itself. Khan – who is of Pakistani and East African descent – concentrated on using the task at hand to communicate the vast amounts of knowledge and innovation that are native to the Middle East and nearby regions, yet are often left out of rhetoric.

“The entry portals feel monumental because of where they appear in the sequence [of arrival], and that is something that was planned. That moment of arrival – the threshold needed to be monumental and memorable – [is on] a scale appropriate to welcome guests to Expo 2020,” Khan says.

Standing 21 metres high and wide and 30 metres long, and woven entirely from strands of ultra-lightweight carbon fibre, the portals are formed of a series of translucent 2D planes in a repeating geometric pattern – referencing mashrabiya – and layered to create a 3D design that is the result of complex structural engineering, where each and every line contributes to holding the structure in place.

“If you look at the different scales – for example, the sub-atomic and then the human scale – they are all connected, and this relates to the importance of science and the convergence of science and art in religion, which are really important topics to me and this region. These themes come up a lot and cross over in the public realm project,” says Khan.

“The idea from HE Reem Al Hashimi was to build a place full of details and stories from the region,” he continues. “I loved her thought that the Expo can be an opportunity to communicate that cultural value to the world, not only in the way it looks to history but in the way it looks to the future as well. That is what we tried to do, in the spirit of the UAE and Dubai, but also in the spirit of the World Expo. Her Excellency was always saying, ‘Think of the public realm as the biggest pavilion on the Expo site. It is the place that connects all the people and the countries.’”

Khan remembers his first day at the Expo 2020 site in 2016, during his second visit to Dubai: “I said, ‘I just want to go out there and walk on this site and get a feel of it’ and it was quite unexpected [for me] to say this, I think. I went out – I was wearing a suit – and I took my shoes off and I walked around with bare feet on the sand. It was a very powerful moment for me. I was trying to connect with things deeper or more distant. I was trying to read the landscape and get some clues.

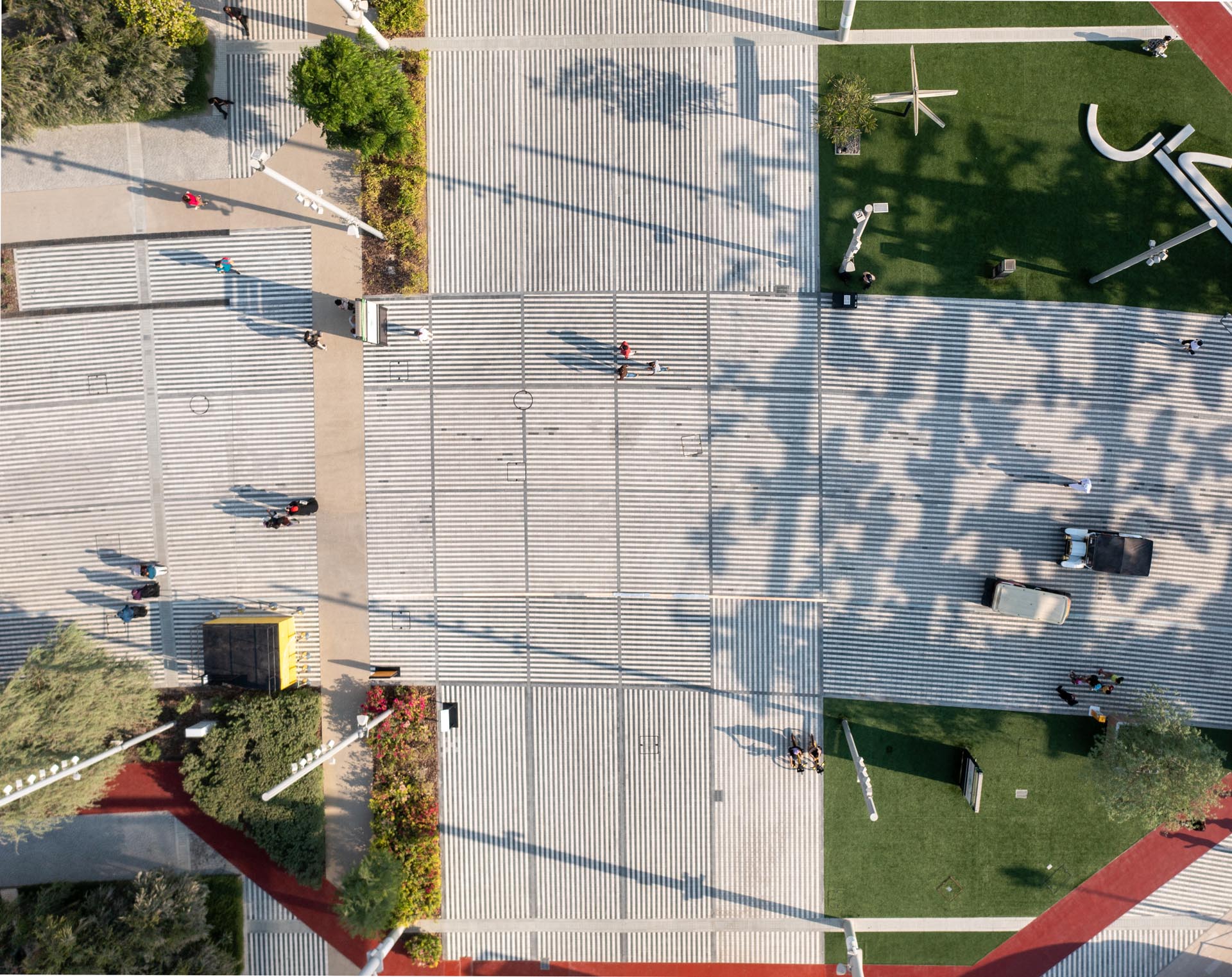

“What I noticed when I was walking there was that there were tracks in the sand and the tiny tracks of animals, of vehicles and of people walking, and all these things overlapped. What I realised is that the overlapping of paths is part of the natural vocabulary of the desert. While they change and shift over time, it is the way the desert remembers the ideas that have transferred across it.”

This overlapping of different tracks that reflect different modes and speeds of human movement led to the creation of the six kilometres of pedestrian walkways using different materials – ranging from grass to gravel – and elements, such as a running track and buggy lane. All these various sections for travel across the Expo site are complemented by a six-kilometre linear belt of greenery and trees, comprising a variety of different plant species, with pockets for rest in between. At times, the different lines interweave and merge to create Al Sadu weaving motifs as wayfinding, marking different venues, resting areas and crossing points – a metaphor for the idea of connection that relates to the overall theme of the Expo.

This is only one of the many delightful nuances that Khan has imagined for the public realm, many of which are so subtle that one must periodically visit the site to gain a full understanding of the many narratives that weave across its public spaces. Another example is his collaboration with Emirati contemporary artist and water colourist Abdul Qader El Rais, who invented two distinct colours for the columns in the public realm – including the ones that hold up the shading canopies. ‘Ghaf Green’ and ‘Ghaf Grey’ are inspired by the bark and canopy of his favourite ghaf tree that sits outside his home and studio.

Another important collaboration was that of the calligraphic benches, designed by Lebanese digital typographer Lara Captan. The concept of the benches relates back to Khan’s research of the landscape, and reading the works of poets from the region that best helped him gain a deeper understanding. “I started to understand that the Arabic word, in its written form, was something very precious and that the written word carried so much of the meaning, wrapped up in the way it is written, through its physical strokes,” Khan explains.

For the benches, Captan designed a typeface that is an extension of the different calligraphic traditions, with the aim of showcasing the nuances of the handwritten form so they are not lost in the age of digitisation.

“By making these benches as script forms, I wanted to draw attention to the importance of Arabic script and how it binds together so many countries that share Arabic as a common language. This was particularly important to me at this international Expo, to show visitors how important this language is to the region and how it has timeless value. My hope is that if you are a visitor from overseas, you may learn a word of Arabic or you may learn the appearance of an Arabic word. And by placing these benches throughout the public realm, and by a visitor sitting on them at various times during their day, they are constructing a poem word by word,” Khan shares.

One of the interesting elements of the benches is how the forms of the words (which were crowd-sourced via social media) mirror their meaning. “What you’ll notice is that words like ‘friendship’ are more inward-facing and encourage people to sit together, and words like ‘vision’ make you look to the horizon. Lara Captan and I tried for it to be a bit of a linguistic experiment. We called it a socio-linguistic experiment, where each word form is created to make you inhabit it in a certain way. It comes to life in the way it is used, and the usage is significant of its meaning.”

Khan and his team also developed a special lighting system called ‘Second Sunset’, which has been matched to the shade of Dubai’s golden hour and extends beyond sunset by 40 minutes, gently moving on to a warm white shade; then, in the night, it changes again to a warm candlelit glow. “It uses the natural triggers that are part of our circadian rhythm and is a new approach to the lighting of cities,” he shares.

Khan has also designed the Garden in the Sky observation deck which, over time, will become a flourishing garden. It stands 55 metres high and rotates to offer panoramic views over the entire site and beyond. The Worker’s Monument, made from Omani limestone, was the last piece of the puzzle and commemorates the 200,000 workers who have helped build the Expo.

“I’m really proud of what we have achieved,” says Khan. “It’s somewhere I personally love being and seeing people interact with it. It feels as though it has been there for a long time, which is something unexpected for a new place. I think this comes from trying to build something with a sense of place, through observation and research.

“I think it’s a powerful prototype for another way of living in Dubai; another kind of urban mode,” he continues. “In the spirit of the Expo, each generation has to add to the discourse of urban design as well as architecture and engineering, and I feel we’ve done that.”

The Latest

Elevate Your Reading Space

Assouline’s new objects and home fragrances collection are an ideal complement to your reading rituals

All Aboard

What it will be like aboard the world’s largest residential yacht, the ULYSSIA?

Inside The Charleston

A tribute to Galle Fort’s complex heritage, The Charleston blends Art Deco elegance with Sri Lankan artistry and Bawa-infused modernism

Design Take: Buddha Bar

We unveil the story behind the iconic design of the much-loved Buddha Bar in Grosvenor House.

A Layered Narrative

An Edwardian home in London becomes a serene gallery of culture, craft and contemporary design

A Brand Symphony

Kader Mithani, CEO of Casamia, and Gian Luca Gessi, CEO of Gessi, reflect on the partnership between the two brands

The Art of Wellness

Kintsugi in Abu Dhabi, situated in a seven-storey villa, offers the ultimate zen retreat

Design Take: Inside the Royal Suite at Jumeirah Al Naseem

With sweeping views of the ocean and Burj Al Arab, this two bedroom royal suite offers a lush stay.

Elevated Living

Designed by La Bottega Interiors, this penthouse at the Delano Dubai echoes soft minimalism

Quiet Luxury

Studio SuCo transforms a villa in Dubailand into a refined home

Contrasting Textures

Located in Al Barari and designed by BONE Studio, this home provides both openness and intimacy through the unique use of materials

Stillness, Form and Function

Yasmin Farahmandy of Y Design Interior has designed a home for a creative from the film industry