Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Art Dubai continues to put the Global South at the forefront of its programming

The 2023 edition of Art Dubai saw the highest number of galleries from Africa and the Global South

As art across the Global South begins garnering more international attention, identity speaks to Pablo de Val, artistic director at Art Dubai, and Vipash Purochanot, the 2023 curator of Bawwaba, about the fair’s efforts in keeping these artists and galleries at the forefront

How is Art Dubai responding to what is going on in the art world today, and in what way is it setting its own agenda? PV: We believe art fairs must react to the needs of their local communities, and this philosophy helps us set a unique agenda that brings all the key players across our region together. We see ourselves as a convener of great minds and an entry point to our vibrant cultural ecosystem. A key element of this is showing top-quality art and artists that you simply will not see at any other art fair – and showcasing them first.

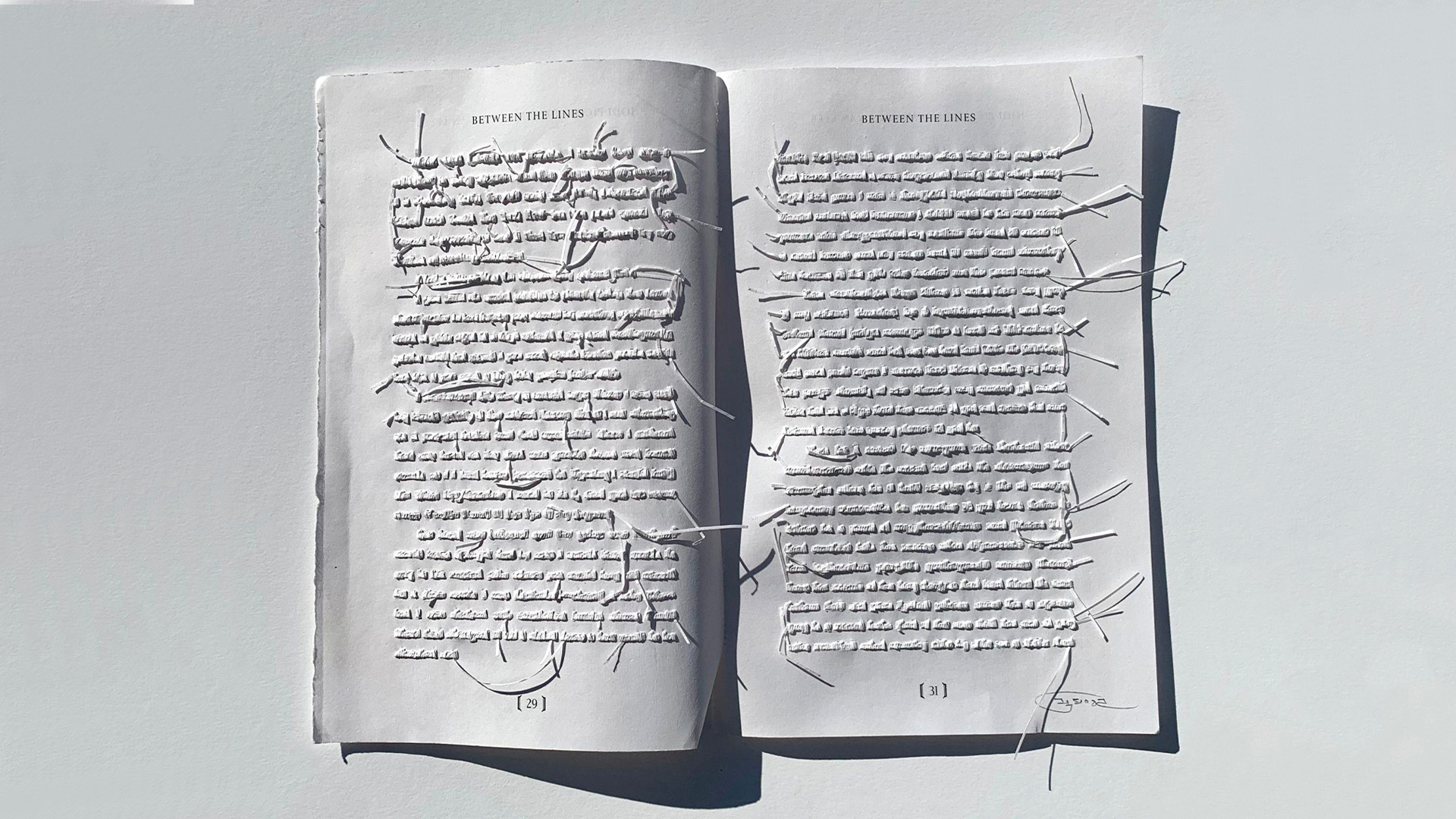

Saad Qureshi (Pakistan, 1986) Sacred Geometry – 2022 – Woven paper – 15 x 13 in – Courtesy Aicon Gallery

How has the fair been involved in getting better representation for artists across the Global South as a whole, and do you think there is a greater appreciation for works from this part of the world? PV: Our role has always been to amplify the voice and heighten the vision of all up-and-coming cultural artists from the Global South, who have been historically underrepresented in the mainstream, largely Western-focused art world. It is something we have been doing since our first fair in 2007, and today there is so much more appreciation for works from the areas of the world we have always championed. Interest in the artistic communities from the Global South grows year on year, and Dubai now has a thriving art scene that is internationally recognised as a centre of creative talent; one that incubates and supports and gives voice to that talent. Our event gets more ambitious each year, and in 2023 more than 130 galleries from all around the world will be at the show.

Dickens Otieno

What is the significance of the theme of this year’s Bawwaba? VP: Bawwaba, which means gateway in Arabic, is dedicated to presenting new work by galleries and artists from the Global South. It offers visitors an analysis of current artistic developments through ambitious solo presentations from 11 artists who [this year] originate from Brazil, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Morocco, Nepal, the Philippines and the UAE. As the curator of the section, I have given it the title ‘Against Disappearance’, to highlight the artists’ shared endeavour to make visible the level of skill involved in creating works of art when such qualities of workmanship and artistry are disappearing from all aspects of life in the 21st century.

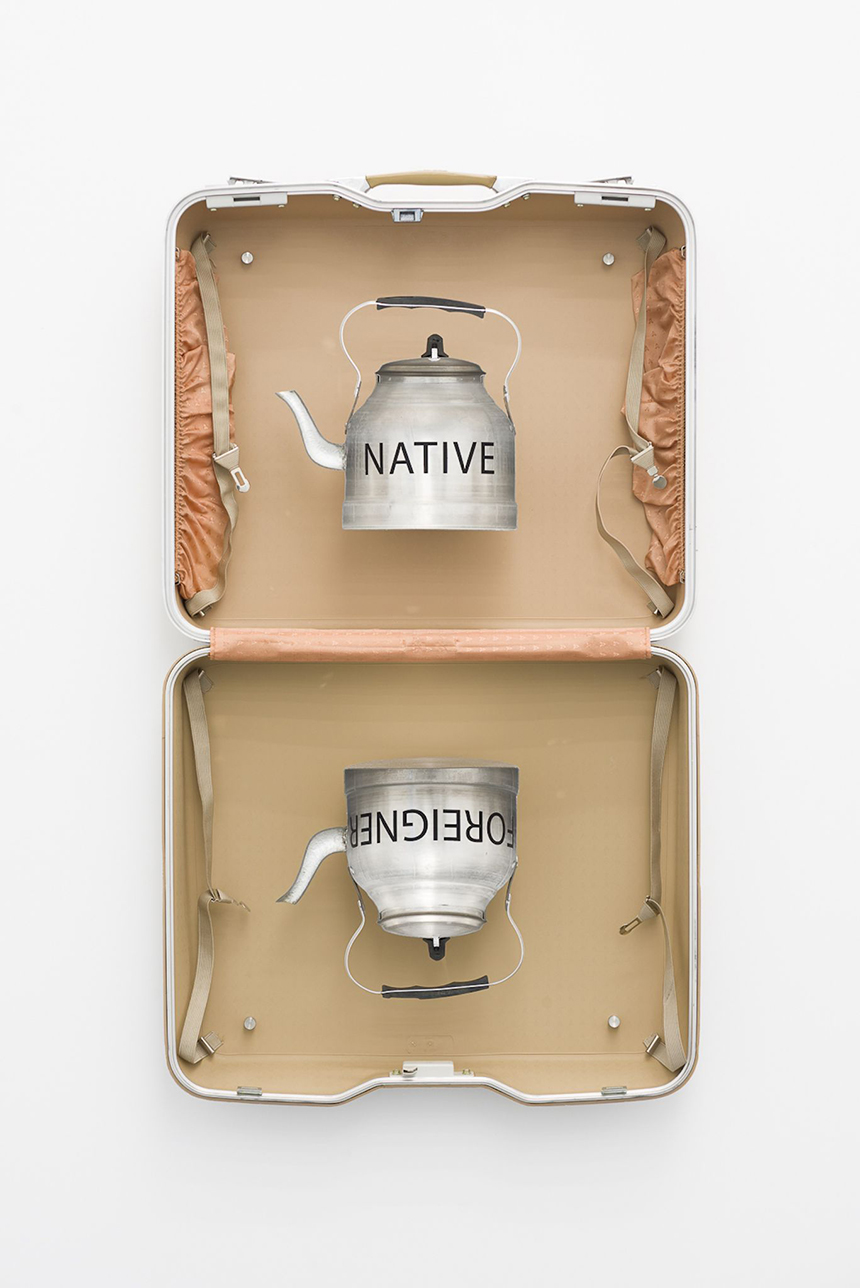

Pascal Hachem (Lebanon, 1979) – Special Case – 2021 – Suitcase and teapot – 94h x 56w cm – Courtesy Selma Feriani Gallery

The theme is the very antithesis of the modern world, characterised by instant technology, whether it’s smartphones, tablets or computers. The contemporary world can be fast-paced and shallow, and attention spans are short. The artists showing in Bawwaba have responded to this through the art of lingering. They have turned to vigorous tasks that expand their attention spans through obsessive detail. In contrast to the act of swiping a finger and scrolling a screen, these artists work with their hands, creating works of art to hold and behold. Their works also underline where they come from, as well as the world [as a whole].

Filipe Branquinho (Mozambique, 1977) – It’s Not a Purse It’s a Fendi – 2022 – Mixed media on Innova cotton rag 315gsm – 110 x 110 cm – AKKA Project

Can you give examples of how some of the artists in Bawwaba carry these processes in their work? VP: Nepali artist Youdhisthir Maharjan [for example] works with paper. He finds books in thrift stores, then meticulously cuts out individual alphabets from them, weaves strips from their pages and assembles them into works of art. Similarly, Gregory Halili, a Filipino artist, works with translucent capiz shells, a traditional material from the archipelago. He has developed a technique that allows him to paint at a miniature scale on a shell’s delicate surface.

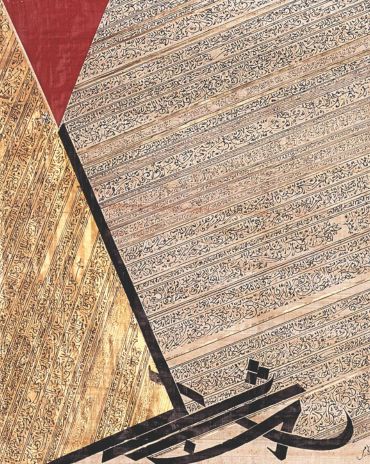

Maha-Malluh-Untitled-2022-62-x-21-cm.-Courtesy-Selma-Feriani-Gallery-and-the-artist.jpg

In contrast to Halili, who uses precious materials, Dickens Otieno creates beautiful tapestries from everyday materials. The Kenyan artist weaves shredded aluminium cans into artworks using a technique normally meant for natural materials such as papyrus, raffia or palm. The colours and patterns of his works are inspired by his memory of his mother’s tailoring workshop in the shifting environment of Nairobi. By using discarded materials, Otieno also interrogates sustainability through his art.

The Latest

Things to Covet

Here are some stunning, locally designed products that have caught our eye

An Urban Wadi

Designed by Dutch architects Mecanoo, this new museum’s design echoes natural rock formations

Studio 971 Relaunches Its Sheikh Zayed Showroom

The showroom reopens as a refined, contemporary destination celebrating Italian craftsmanship, innovation, and timeless design.

Making Space

This book reclaims the narrative of women in interior design

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage