Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Adjaye Associates’ Edo Museum of West African Art aims to reconnect people with their history

The new museum is designed to engage local communities and reclaim history

Adjacent to the Royal Palace of the Oba in the centre of Benin City is a site that will house the new Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA), designed by Adjaye Associates, a practice led by Ghanaian-British architect, Sir David Adjaye. Developed by the Legacy Restoration Trust (LRT), the ambitious architectural endeavour is also associated with an archeological initiative being developed by LRT in partnership with the British Museum as well as other partners in Nigeria, and Adjaye Associates. The project aims to investigate the archaeology of the ancient Kingdom of Benin – in modern-day Nigeria – the remnants of which are buried below the proposed site of the new museum, including what is believed to be preserved buildings and traces of elaborate pavements made of pottery fragments that were revealed during test excavations in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Excavation works will take place prior to the construction of the museum and will continue for a period of five years. The project is developed with the approval of the Benin Royal Court and the Edo State Government, and in partnership with the National Commission for Museums and Monuments as well as a range of partners from local communities.

Images courtesy of Adjaye Associates.

The new museum, which will house West African art and artefacts as well as contemporary collections from the continent, aims to create new ways of engaging local communities and reconnecting people with their history. It is also focused on reuniting important Benin artworks and artefacts that had been looted during the invasion and destruction of Benin City by British forces in 1897; a time where the Kingdom of Benin was established as one of the most important and powerful pre-colonial states of West Africa, and a major trading state. The city’s shrines, royal chambers and storerooms were ransacked, and thousands of objects of ceremonial and ritualistic value were looted. Benin City remains renowned for its castings in brass and bronze; one of the most prominent artefacts looted from the Kingdom is the Benin Bronzes, including several hundred plaques that depict narratives of the life of the Kingdom. Many of these artefacts are currently on display across museums in the UK, Europe and the USA, with the British Museum currently holding over 900 objects from Benin, including more than 100 that are on public display.

For Adjaye, the museum is an opportunity to reclaim and reteach the history of the ancient Kingdom of Benin through an interrogation of its “thriving civilisation” that predated its colonial history.

“There is an incredible legacy handed down to us by our ancestors that has largely been unheard or close to forgotten,” Adjaye tells identity. “EMOWAA is not intended simply as a space in which the Benin Bronzes are returned but a space in which history is re-situated and re-understood. The artefacts are sacred objects that hold the ability to restore the stories of an ancient kingdom and renew the ancient intelligence of the African past. For me, the possibility of re-storying history through disrupting and decentralising typologies of architecture is something that plays heavily in my works, and the possibility of doing this on African soil will, I believe, spark an African Renaissance.” He adds that the integral first step towards restitution is establishing the infrastructure that will enable the return of these artefacts.

“The conception of this museum entails an interrogation into a particular trajectory of colonial history, to uncover West Africa’s thriving civilisation before the colonial encounter,” Adjaye continues. “The project asks what a museum on the African continent in the 21st century can really be, and in this sense it occupies the temporal scales of reclaiming the past in a post-colonial moment and to use this reclamation as a re-teaching tool in the present to ensure a re-storying of history and ancestral wisdom to influence future generations.”

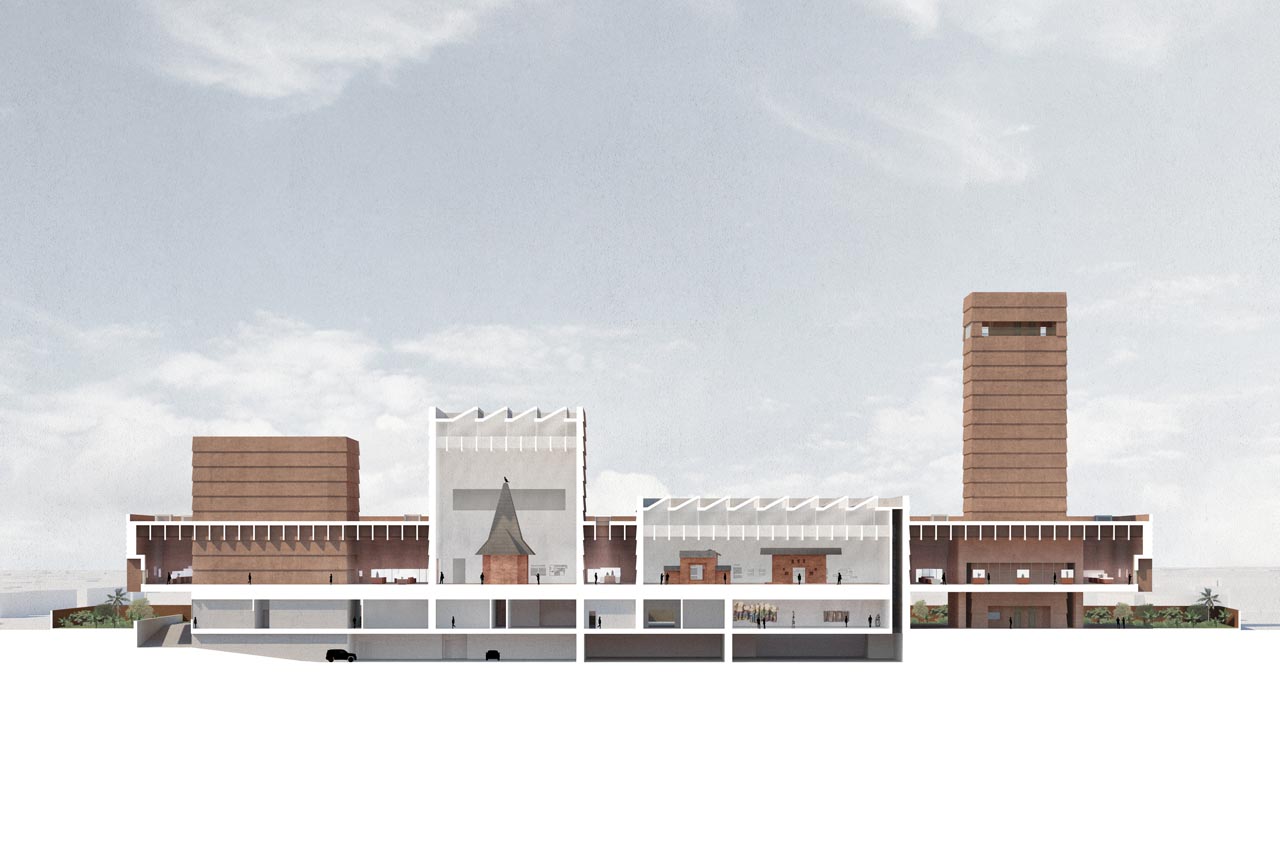

The architectural proposal for EMOWAA connects the museum with its surrounding landscape by revitalising and incorporating the surviving remains of the walls, moats and gates of the historic city. Inspired by this historical architectural typology, the museum’s design includes a courtyard in the form of a public garden with various indigenous flora and a shading canopy, creating a green space for gathering, ceremonies and events.

“In the way that the artefacts connect through ritual to the people, the museum connects through its spatial design to the community by providing an infrastructure to gather for social events, outdoor and indoor festivals, ceremonies, lectures and education spaces,” Adjaye explains.

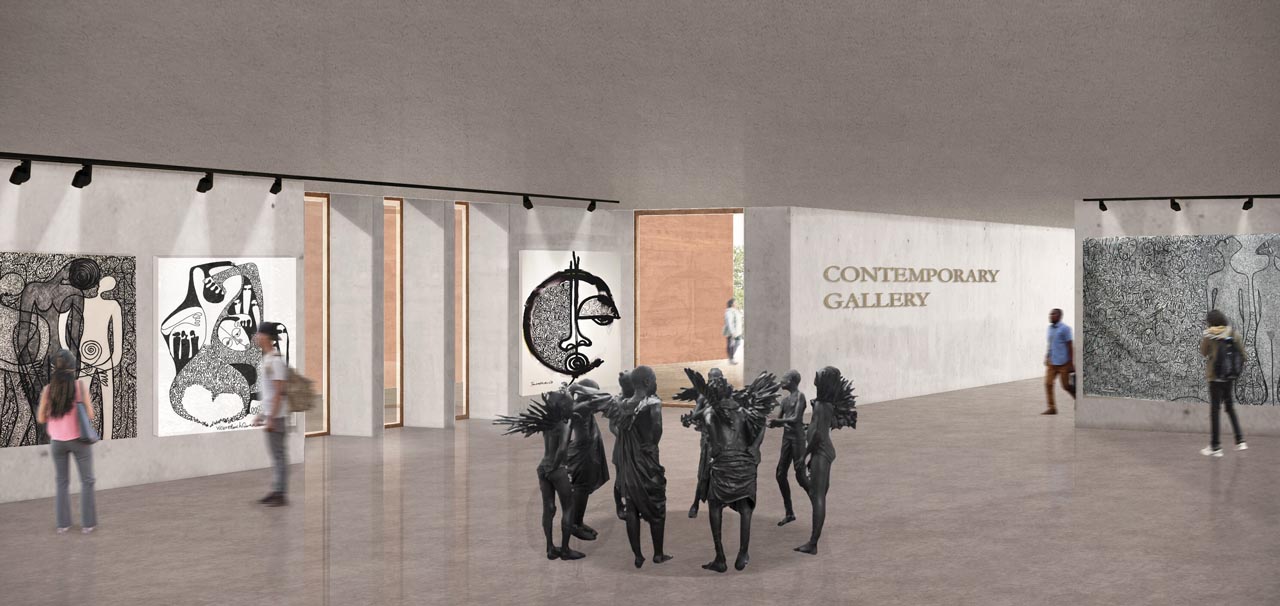

A series of elevated volumes float above the gardens, making up its galleries, within which sit pavilions inspired by “fragments of reconstructed historic compounds” that allow the objects to be arranged in their pre-colonial context. This creates a scenario in which visitors can better understand the true significance of the artefacts and their significance within the culture of Benin City, from traditions, politics and economics to rituals.

“EMOWAA operates both as a museum and a community centre meant to engage visitors on a global and local scale,” Adjaye explains. “The objects and artefacts once seized from Benin were intrinsically connected to rites and ceremonies of the Benin people, some even recording historic events of the Kingdom’s past. This is an archival history that provides a great advantage to Nigerian and international scholars, as well as the larger community, who now have the opportunity to understand their history.”

It is hoped that the archaeological finds uncovered during the excavations, which are set to begin in 2021, will be retained in their original position in order to become part of the visitor experience of the new museum.

“The architecture of EMOWAA is in intimate conversation with its archaeological counterpart, and what is represented internally or programmatically through the representation of Benin history is also represented externally or architecturally. The archaeology is used as a means of connecting the new museum through design into the surrounding landscape,” Adjaye says.

Read more: David Adjaye to receive 2021 RIBA Royal Gold Medal

The Latest

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.

Asterite by Roula Salamoun

Capturing a moment of natural order, Asterite gathers elemental fragments into a grounded formation.

Maison Aimée Opens Its New Flagship Showroom

The Dubai-based design house opens its new showroom at the Kia building in Al Quoz.

Crafting Heritage: David and Nicolas on Abu Dhabi’s Equestrian Spaces

Inside the philosophy, collaboration, and vision behind the Equestrian Library and Saddle Workshop.

Contemporary Sensibilities, Historical Context

Mario Tsai takes us behind the making of his iconic piece – the Pagoda

Nebras Aljoaib Unveils a Passage Between Light and Stone

Between raw stone and responsive light, Riyadh steps into a space shaped by memory and momentum.