Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

ZAV Architects designs colourful domes for residential project in Iran

'Presence in Hormuz' pays homage to its environment and people

Following the 2014 decision to annex Hormuz Island to the Free Trade Zone of Qeshm, plans to boost the quality of life for the 42-square kilometre piece of land that sits just off the west coast of Iran were put into action. The scheme was multi-fold, focusing on providing economic stability by drawing upon the island’s inherent attraction for tourism, and manifested in the ongoing urban-tourism intervention, ‘Presence in Hormuz’, a year later.

Located on the uppermost crest of the island, Presence in Hormuz consists of three projects: Rong, a cultural centre that receives tourists on arrival; Majara Residence, a visitor’s accommodation; and Badeban Centre, a training centre to equip locals with hospitality skillsets. The assertive programme involves the help of the island’s long-standing community in its construction and future maintenance, and is designed by ZAV Architects, a Tehran-based practice that views architecture as a means to economic advancement for investors and local communities alike, as well as on a national scale.

While Rong was completed in 2017, Majara Residence was completed in 2020 and features 200 small-scale domes built with the superadobe technique of Nader Khalili, an Iranian architect who founded CalEarth in 1991, an American institute that ZAV consulted with for the project. Inspired by traditional water storage structures known in the region as āb-anbār and ranging in size – 123 domes have a diameter of three metres, while the remaining 77 have a diameter of four or more metres – the buildings are made of cement plaster. The larger ones were further reinforced with steel structures to provide different dome shapes in the project’s skyline. Varying the shape of the domes, which differ in pointedness, is intended to evoke a carpet woven with granular knots.

The colours of the structures, which shift from mustard yellow to firebrick red, maya blue to moss green, draw inspiration from the island’s geological features, which have aptly inspired Hormuz’s nickname as the ‘rainbow island of Iran’.

For ZAV, the domes’ dim interiors are meant to evoke the feeling of being in a cocoon of sorts, where calmness, stillness and darkness combine to forge a reconnection between users and nature.

“When you take a few steps out of the water-storage-like structures, you experience a unique open horizon towards the sea,” says ZAV’s founder and senior architect, Mohammadreza Ghodousi, about the minimal use of openings. “The interiors are designed to be colourful spaces that are closer to the earth, inviting users to leave any tension behind them, and to be embraced.”

Throughout Majara Residence, paved pathways intersperse the domes, and as the sowed vegetation grows in, birds find their nesting places on rooftops and antelopes find comfort in the shade. Respecting the environmental needs of the island and creating economically-responsible developments are the practice’s main principles, which are reflected throughout the project, from its design to its construction. Another example is ZAV’s refrain from using the clay soil of Hormuz Island in the domes’ building material, which has a history of being wrongfully extracted due to its rich red colouring. Instead, the architects increased the proportion of sand soil.

Additionally, as the superadobe technique involves filling sandbags and ramming them, it requires a lot of labour on-site, with more masons needed than engineers. However, for ZAV, the idea to rely less on technology and more on local workforce was a priority.

“This made it possible to work with the people of the island,” says Ghodousi. “But because diversity of the needed working skills was limited, training became easier and easier.”

And while superadobe master masons, blacksmiths, painters and more were being trained during the construction of Majara Residence, travel guides, reception clerks and others were being trained in the Badeban Centre, which will be completed in 2021. The latter group, who are also being taught English, are intended to manage the operations of the hospitality development post-completion. The two-part training structure installed by ZAV ensures that the people of Hormuz can benefit from the project during construction and after.

ZAV is fiercely principled in its work – it often attempts to converge the benefits of investors and the local community with largescale national agendas through architecture, construction and implementation. It also aims to produce an architecture that mimics nothing, but rather, relies on collective creativity. And such values are present in Majara Residence, the architecture of which is centred on geographical lines, featuring the colours of the island, and showing pride in Hormuz’s locality and heritage.

“Architectural projects do not necessarily need expensive lands and high technology, which usually put extra pressure on national economies,” says Ghodousi. “Architecture can be productive in job creation during construction and bring added value for society. After completion and during implementation, it can also help a city’s branding and reputation, and impact the region positively.”

Photography by Tahmineh Monzavi, Soroush Majidi, Payman Barkhordari.

The Latest

The language of weave

Nodo Italia at Casamia brings poetry to life

The Art of the Outdoors

The Edra Standard Outdoor sofa redefines outdoor living through design that feels, connects and endures

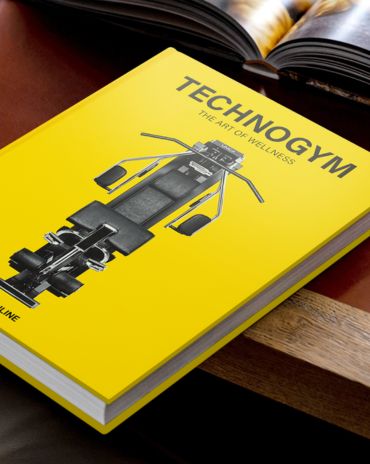

The Art of Wellness

Technogym collaborates with Assouline to release a book that celebrates the brand’s 30-year contribution to the fitness industry

The Destination for Inspired Living – Modora Home

Five reasons why you need to visit the latest homegrown addition to the UAE’s interiors landscape

Elemental Balance — A Story Told Through Surfaces

This year at Downtown Design 2025, ClayArk invites visitors to step into a world where design finds its rhythm in nature’s quiet harmony.

The identity Insider’s Guide to Downtown Design 2025

With the fair around the corner, here’s an exciting guide for the debuts and exhibits that you shouldn’t miss

A Striking Entrance

The Oikos Synua door with its backlit onyx finish makes a great impression at this home in Kuwait.

Marvel T – The latest launch by Atlas Concorde

Atlas Concorde launches Marvel T, a new interpretation of travertine in collaboration with HBA.

Read ‘Regional Excellence’ – Note from the editor

Read the magazine on issuu or grab it off newsstands now.

Chatai: Where Tradition Meets Contemporary Calm

Inspired by Japanese tea rooms and street stalls, the space invites pause, dialogue, and cultural reflection in the heart of Dubai Design District

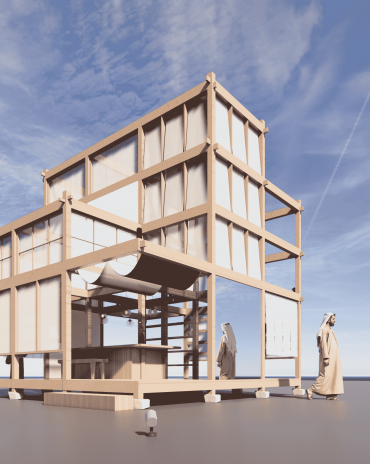

A Floating Vision: Dubai Museum of Art Rises from the Creek

Inspired by the sea and pearls, the Dubai Museum of Art becomes a floating ode to the city’s heritage and its boundless artistic ambition.

Heritage Reimagined

Designlab Experience turns iconic spaces into living narratives of Emirati culture, luxury, and craftsmanship.