Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Sahel Al Hiyari’s monolithic Barghouti House integrates into the landscape

The Amman-based building aims to preserve its endangered landscape

Set on an undulating landscape of hills that were once covered in abundance by native oak trees, Barghouti House appears to have independently landed onto the site. At first glance, the monumental structure seems less like a residence and more like a civic or cultural building. Upon closer inspection of its many nuances – its sensitive embrace of the surrounding landscape, the gaps in the structure that result in interplays of light and shadow, the hand-sanded delicacy of the façade and the floor-to-ceiling windows that reveal a rich interior – one is immediately taken by the warmth against its brutal structure.

“The quality of materiality plays an important role in the general ‘style’ of the house, where its hand-sanded concrete surfaces undulate to create an imperfect, vibrating body that allows the structure a softer tactile feel, which is not really commonly sought in reinforced concrete buildings of this type,” says Jordanian architect Sahel Al Hiyari.

The house is located in Dabbouq, a residential district set to the west of Amman – an area that has seen mass development, resulting in environmental damage to one of the few forested areas in the Jordanian capital. For this reason, Hiyari’s sensitive approach has been to navigate the building around the existing landscape so as not to cause further damage to the area. Instead, the single-family villa – which is located on a rectangular lot of land – is skewed in relation to the existing topography, aligning it with the direction of the sharp diagonal slope that extends from one corner of the site to the other.

“The orientation of the house does not follow the lot lines, but rather adheres to the direction of the topographic lines. The site has several mature oak trees indigenous to the area, which was another determining factor as to how the house would be located. For this reason, the structure was located at the mid-section of the site, which was the only clear space with no trees,” Al Hiyari reveals.

“In essence, the project succumbs to the site conditions and does not attempt in any manner to transform them. The strategy accepts the conditions in their totality and internalises them as design tools.”

The three-floor residence consists of two separate masses that are connected by a partial roof, framing the views over the landscape; each level connecting to the garden. The divided sections of the house allow for each mass to act independently of the other, allowing one of the parts to act as a private apartment within the overall villa.

While the garage is set at the back of one of the separate masses due to the L-shaped configuration of the house, most of the spaces are arranged in a formation of rows directed towards the views to the outside. The main ground floor contains the main functions of the house, while the basement level offers service spaces and a multi-purpose hall.

The main arrival space has been set at the highest part of the land and is entirely closed apart from the garage and the main entry of the house, which is carved out from the landscape and accessible by two stairs of different scales. This entry courtyard actually opens up both to the sky, through the roof, and the landscape across the site, which can also be seen through the interior spaces.

“Each space is carved within the thick slabs that make up the massing of the house,” Al Hiyari explains. “This has consequently allowed a variety of spatial conditions to occur within the interior in terms of heights, size and levels. The common denominator between all spaces is the unified and recessed widow height that produces continuous slab lines of the external mass. This actually dissolves the spaces within into singular gestures of thick slabs. Therefore, the result is a series of domestically scaled spaces manifesting visibly as suspended monoliths.”

The thick concrete slabs that appear to hover between the land further add to the building’s monolithic quality, while its sculptural form references the surrounding landscape and simultaneously contrasts against it.

Although there is no specific point of reference in this project, Al Hiyari explains there may be apparent similarities to other megalithic architectural works, such as those of Frank Lloyd Wright, that compare in expressions of scale and weight, as well as sculptural qualities. “Our interest extends to the ambiguous qualities of buildings under construction, abandoned structures, and even archaic ruins,” he adds.

For the interiors, Al Hiyari worked with Lebanese design duo david/nicolas, whom he met in 2016 whereupon “sparked an immediate synergy” that resulted in two collaborations, beginning with Barghouti House.

“I was quite impressed with their work,” Al Hiyari confides. “I believe they are extremely talented, knowledgeable and with a very refined sensibility. As a consequence I initiated the collaboration and luckily the client also admired their work.

“What is quite interesting about david/nicolas is that they are product designers through and through. So, their contribution not only consisted of the selection of furniture, fabrics and so on, but also more importantly, the design of specific elements that range from wall panelling to specific furniture and fixtures. Their work brought a fresh energy to the interior, yet one that remained quite harmonious with the architecture of the house.”

Jordanian landscape architect Lara Zureikat, who is behind important projects, such as the Palestinian Museum, was another collaborator on the project. In appropriate style, she used the landscape to further accentuate the architecture. The landscape permeates the architecture in an attempt to articulate its spatial experience with the surrounding nature, while in response, the architecture frames the landscape and allows it to integrate with the built form.

“What is interesting about our numerous collaborations with Lara is her great capacity to work with the architecture without really overwhelming it or being overwhelmed by it,” says Al Hiyari. “This balance is not easy to achieve, especially when a large constituent of the architectural project is actually the landscape itself, as is the case with Barghouti House.”

Much like with the rest of the plot, the landscape of the garden was already quite defined due to the number of mature trees present on the site, which the architects refused to tamper with. The intervention, therefore, included inhabitable pockets within the garden for the family to use.

Al Hiyari adds that the negligence in creating ecologically sensitive environments is predominantly related to a lax set of environmental and building codes combined with a collective social indifference to the damage being done.

“Many write this damage off as inevitable, or unavoidable, or as the price we must pay for development and expansion. More dangerously, I believe, it is a question of a lack of awareness and/or the superficial understanding of the necessary roles that such delicate environments perform. Consequently, the responsibility actually becomes a personal one shared by clients and architects and governed by their individual sense of duty,” he comments.

While Al Hiyari’s work remains a reference for many architects across the Arab world and beyond, the architect insists that his work doesn’t consciously respond to the state of architecture and its development across the Arab world or anywhere else. His focus is mainly concerned with, or based on a closer examination of, the immediate context and conditions of each project.

“Having said that, we also do not work in a void,” he affirms. “The work actually seeks to refract and reflect on the many facets of what may be considered local aspects related to history, nature, resources and social dynamics – to name a few. Therefore, rather than defining a perspective seen strictly through a global lens, our work tends to invest itself in expanding the possibilities and challenges of the here and now.”

Read more: ‘A Thobe Story’ by Naqsh Collective features garments embroidered by Palestinian refugee women

The Latest

Dubai Design Week 2025 Unfolds: A Living Celebration of Design, Culture, and Collaboration

The 11th edition of the region’s leading design festival unfolds at Dubai Design District (d3)

Preciosa Lighting Unveils ‘Drifting Lights’ at Downtown Design 2025

The brand debuts its newest 'Signature Design' that explores light suspended in motion

IF Hub Opens in Umm Suqeim

A New Destination for Design and Collaboration in Dubai

The Language of Weave

Nodo Italia at Casamia brings poetry to life

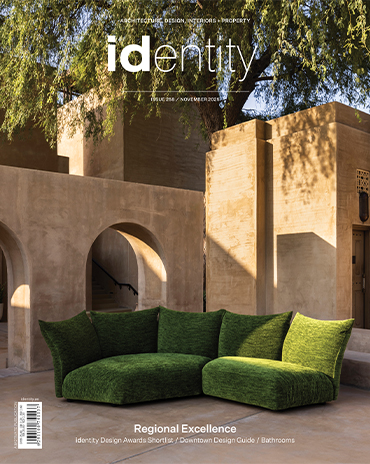

The Art of the Outdoors

The Edra Standard Outdoor sofa redefines outdoor living through design that feels, connects and endures

The Art of Wellness

Technogym collaborates with Assouline to release a book that celebrates the brand’s 30-year contribution to the fitness industry

The Destination for Inspired Living – Modora Home

Five reasons why you need to visit the latest homegrown addition to the UAE’s interiors landscape

Elemental Balance — A Story Told Through Surfaces

This year at Downtown Design 2025, ClayArk invites visitors to step into a world where design finds its rhythm in nature’s quiet harmony.

The identity Insider’s Guide to Downtown Design 2025

With the fair around the corner, here’s an exciting guide for the debuts and exhibits that you shouldn’t miss

A Striking Entrance

The Oikos Synua door with its backlit onyx finish makes a great impression at this home in Kuwait.

Marvel T – The latest launch by Atlas Concorde

Atlas Concorde launches Marvel T, a new interpretation of travertine in collaboration with HBA.

Read ‘Regional Excellence’ – Note from the editor

Read the magazine on issuu or grab it off newsstands now.