Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Interview: Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury on using architecture as resistance

Khoury talks about how his architecture is an embodiment of Beirut's political and urban struggle

identity speaks to Lebanon’s legendary architect, Bernard Khoury, about how a home can be translated from a physical space to the wider city while remaining representative of a political struggle.

Your work consistently tackles the political realities of Beirut. During your earlier years, you wanted to work on a monument for the city but that never materialised. Why was this important to you?

Bernard Khoury: I’ve worked on anti-monuments or anti-manifestos because this was what Beirut was about and this is what Beirut is still about. In my early years of practice, I Iooked at my colleagues in the West with a bit of envy because they were working on noble programmes such as museums and opera houses and hospitals and public buildings and so on. And this was completely absent here in the absence of public institutions. We were operating on very rough territories. The city was totally and completely in the hands of the private sector, so we had to build other strategies and try to find political meaning outside of the conventional territory of architecture, which is usually the monuments and serious institutional buildings. These don’t exist where I come from. Years later looking back, this was not bad because true resistance happens under rough territories and truly meaningful work should be done where it is least expected. At this point in my life, I am not interested in formulating any sort of consensual, political position through a monument because conventional monuments are very consensual. Beirut with all its contradictions has allowed me to sometimes take very radical postures that I would not have been able to take on more conventional and secure territories in the West, for instance.

Your projects saw a massive shift from designing temporary “party” buildings to working with big developers in the country and abroad. What propelled this development in your work?

BK: For the first four to five years of my practice after completing my degree in the late 1990s, yes I was only given temporary projects based on scale and mainly in the entertainment sector. I wasn’t trusted to build permanent buildings, I wasn’t trusted to build large scale projects that had to do with bigger budgets and so on. I wasn’t trusted to conceive dwellings in which people will have to raise their kids because I was immediately classified as the bad boy of architecture. But with that came a lot of media attention. It did not come locally at the beginning but by the late 90s to early 2000s, the three tiny entertainment projects I had built had gotten media coverage that was worth financially many times what it cost to build them. I did not do it for that, but it just came. When the media attention came so did the people who invest money so the second wave of clients were banks, strangely. And then came the developers. In the beginning, there were young developers of my generation who were smart enough to question the prevailing, existing typologies that we were stuck with for the last four decades, which produced very bad dwellings and a very bad urban fabric which is the catastrophe you see in Beirut today. In the beginning, they were smaller-scale developments which ended up being extremely successful. Every time we conceived a building it was sold out before we even applied for the building permits. The success is not something that falls out of the sky or something that happens behind closed doors in my studio. It is an extremely complex process that involves a lot of people and that takes a lot of intelligence to also navigate and construct these relationships in a way that can make these situations possible. A lot of people look at me sometimes very superficially as someone who has served the private sector, someone who has worked with pirates and they tend to think that I am not a good guy. But that is not true (laughs).

You have definitely gained the reputation of a rebel, with many commenting that your projects may be too harsh for the urban landscape or don’t blend in with context. What do you make of that?

BK: I have heard that. There are some people who have a dangerously simplistic definition of what our context is or what our city is. The people who see the sugar-coated postcards and those are very dangerous simplifications of history. I live and breathe on toxic grounds and at least I see it and I recognise it. This is what my work is in context to. I think that the architects that you recognise through their formal approach, or aesthetics or their architectural syntax, are dinosaurs. They are stuck in the stone age because they are stuck in form. Today, we live in an era where meaning is developed and created far more spontaneously through far more dynamic means while unfortunately, architecture is still stuck in matter. I am not stuck in that. I like to think my buildings don’t look like each other.

You have always been quite critical of the way Beirut is being built and the people who are financing and leading its urban development. But then you are also working with high profile clients on big projects across the city. Do you see this as a contradiction?

BK: I am not being critical for the sake of it. When you look at the history of the fast development of the fabric of Lebanon in general or Beirut, it’s interesting to see the glory years of the modern era that came with independence. From the early 1940s up to the early 70s, you had 30 years during which the nation-state was building itself through institutions and institutional projects. It was the beginning of the illusion of the state. It goes bankrupt in the early or mid-70s. I start my career in the late 90s at which point there is no state in the real sense of the term and with that, no mechanisms to regulate the development of the city and its fabric. The problem is political, it is not architectural. We are really at the end of the chain. The problem when it comes to architecture is that an overwhelming number of architects abided by or did not take any relevant courageous postures to try, within the limits of our profession, to do something. I would say, however, that through even our presidential projects with developers, we did take suicidal postures sometimes. But they are incidents on single plots in the middle of an ocean of an aggressive fabric of buildings surrounding us. A very good example is the ship building [Plot # 1282 designed by Khoury] which is open on 100 per cent of its periphery, while 98 per cent of its periphery is surrounded by private plots who could turn their backs to us. That’s what I call a suicidal posture.

But to a commercial client, these are not the typical narratives that sell.

BK: Well this is where the supposed intelligence of the architect comes in. The intelligence of the architect is not in his ability to manipulate architectural syntax in the correct way or to produce pretty buildings. I have absolutely no interest in that at all. I’d rather look at what people point out as a terrifyingly ugly building if that makes sense. I have absolutely no interest for polished, smooth, cynical, well-behaved architecture; that to me means nothing. So, it is very important for the architect to work on what precedes the architectural act, to construct a relationship with the client that allows you to have a dialogue and a discourse that is more profound than just producing well behaved, catalogued good architecture.

Tell us about your own home in Beirut that you’ve designed.

BK: This started back in 2007-8 when one of the young developers I had been doing many projects with took me to a plot and was very hesitant about purchasing it because right next to us was the Maronite cemetery and to our back was another cemetery and so on. I immediately encouraged him to take that plot which was a very good deal. It was very affordable probably because of the presence of the cemetery and also because of its proximity to the demarcation line. To encourage him to take the plot, I told him I would take the last eight metres of the land. So I built a box or a house on top of the building, that rests on the building but has an internal structure that’s dependent on what’s underneath it. Call it a house perched on top of a building.

All around us are low rise or landscaped plots which is truly exceptional in Beirut. On a clear day, I see uninterrupted views way beyond the southern suburbs of the city. It’s this big rectangular picture frame that you see from the street and the main window of the living area around which all the vital functions of the house are plugged into. But this big volume is completely open through that window and through the uninterrupted views you can see in the background, the catastrophic fabric of Beirut. And I see that every morning when I wake up as the most frightening picture of what the political situation has produced. I look at Beirut in its marvellous horror and I love it. On top of that, I have a terrace with a very decadent posture that allows me to float and see the landscape. Above all of that are two cannons [that are in fact lights] pointing south towards the enemy, but who the enemy is, is another story.

You can say then you have a strangely positive relationship with your home…

BK: My relationship with my house is the most calm and emotional relationship that you could have with Beirut which you have to love and admire because she is ugly as hell, she stinks, she is dirty, she lies, she is toxic, but there is something absolutely marvellous about her. My home is Beirut in all its horrors and all its splendour.

This article is originally published in identity’s June 2020 Home Issue.

The Latest

The language of weave

Nodo Italia at Casamia brings poetry to life

The Art of the Outdoors

The Edra Standard Outdoor sofa redefines outdoor living through design that feels, connects and endures

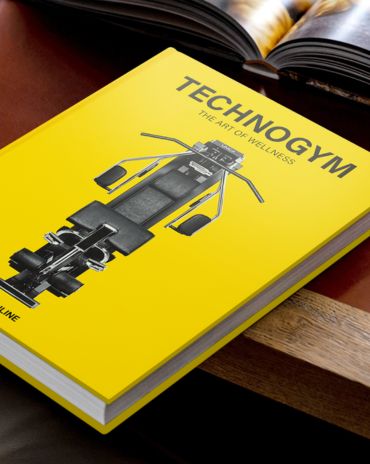

The Art of Wellness

Technogym collaborates with Assouline to release a book that celebrates the brand’s 30-year contribution to the fitness industry

The Destination for Inspired Living – Modora Home

Five reasons why you need to visit the latest homegrown addition to the UAE’s interiors landscape

Elemental Balance — A Story Told Through Surfaces

This year at Downtown Design 2025, ClayArk invites visitors to step into a world where design finds its rhythm in nature’s quiet harmony.

The identity Insider’s Guide to Downtown Design 2025

With the fair around the corner, here’s an exciting guide for the debuts and exhibits that you shouldn’t miss

A Striking Entrance

The Oikos Synua door with its backlit onyx finish makes a great impression at this home in Kuwait.

Marvel T – The latest launch by Atlas Concorde

Atlas Concorde launches Marvel T, a new interpretation of travertine in collaboration with HBA.

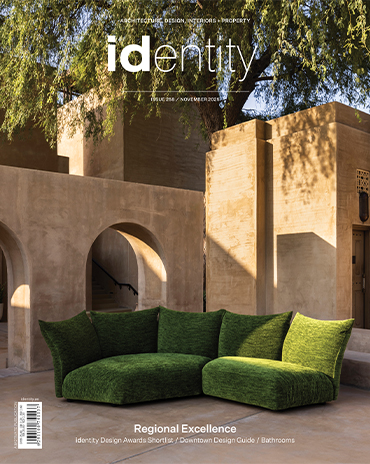

Read ‘Regional Excellence’ – Note from the editor

Read the magazine on issuu or grab it off newsstands now.

Chatai: Where Tradition Meets Contemporary Calm

Inspired by Japanese tea rooms and street stalls, the space invites pause, dialogue, and cultural reflection in the heart of Dubai Design District

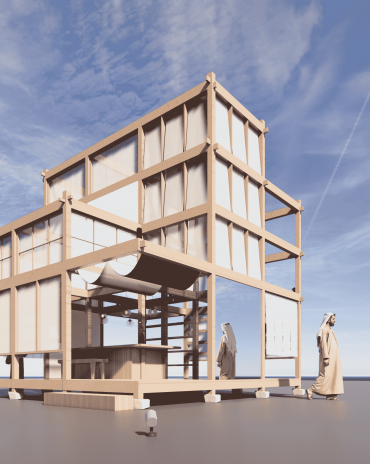

A Floating Vision: Dubai Museum of Art Rises from the Creek

Inspired by the sea and pearls, the Dubai Museum of Art becomes a floating ode to the city’s heritage and its boundless artistic ambition.

Heritage Reimagined

Designlab Experience turns iconic spaces into living narratives of Emirati culture, luxury, and craftsmanship.