Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

The Solar Design Biennale aims to rethink our approach to solar design

Conceived by a pair of solar designers, the biennale looks to how we will design in the future

The world’s largest gathering of sun salutations – the yoga practice that involves reaching one’s arms and head up to face the sun – may produce vast amounts of positive human energy. But can it help power a city? Three women believe it can.

Mirka Laura Severa, Solar Views (The Visitor), 2021

“We want to create a sense of wonder around solar energy and our relationship with the sun,” says designer Pauline van Dongen, co-founder of the Solar Biennale, which opens its first edition in Rotterdam in September this year. “Solar power needs a new story,” adds designer and co-founder Marjan van Aubel. “The standard blue panels are quite ugly.”

The pair are solar designers – or designers working with solar technologies to produce household objects, clothing and industrial products. “I see solar as a material, where surfaces are activators that turn light into energy,” explains van Aubel, who designed a colourful solar-powered roof for the Netherlands Pavilion at Dubai Expo 2020. “Solar design involves thinking about a double function, and how to design for the future,” she adds.

Van Dongen, meanwhile, works with textiles to make wearable solar power, such as a windbreaker for tour guides that can charge GPS trackers and mobile phones. “As a solar designer you work with the energy harvesting technology, while trying to mediate the sun’s other qualities: the connection to nature and circadian rhythms and its colour, emotional connections and ritualistic values.”

Portable Solar Distillery by Henry Glogau (2011)

But the growing field, the pair says, is often overshadowed by the more functional depictions of solar power. “The current narrative is focused on the technocratic approach to solar design, where it’s all about the economics and efficiency of the technology,” says van Dongen. “We wanted to show people that there are viable alternatives, and that’s possible through storytelling and examples of beautiful design.”

The two-month biennial will consist of a lecture series, an exhibition and a public programme of workshops that will bring together designers, engineers, philosophers and policy-makers around the themes of solar power. Among its events is a large-scale gathering in Rotterdam to perform a collective sun salutation.

Pauline van Dongen, ‘Solar Shirt’. Photo: Liselotte Fleur.

It comes as the city of Rotterdam recently announced its ambitions to become Europe’s first solar capital. Soaring energy prices as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic and the war in Ukraine have brought conversations about Europe’s energy transition to the fore. “We’re living in a climate crisis, and we urgently need to change how we deal with energy, and [how we] design society around these more sustainable energy systems,” says van Dongen.

Solar designers say they are contributing to the energy debate by making solar technologies more tangible in everyday life. “For individuals, it can be really hard to grasp these kinds of large transitions, and the influence they can have by making their homes more sustainable,” says van Dongen, “Often, [transitions] are forced on them from a top-down perspective. We want to show that there are ways to engage people from the bottom up and to excite them first and start a dialogue.”

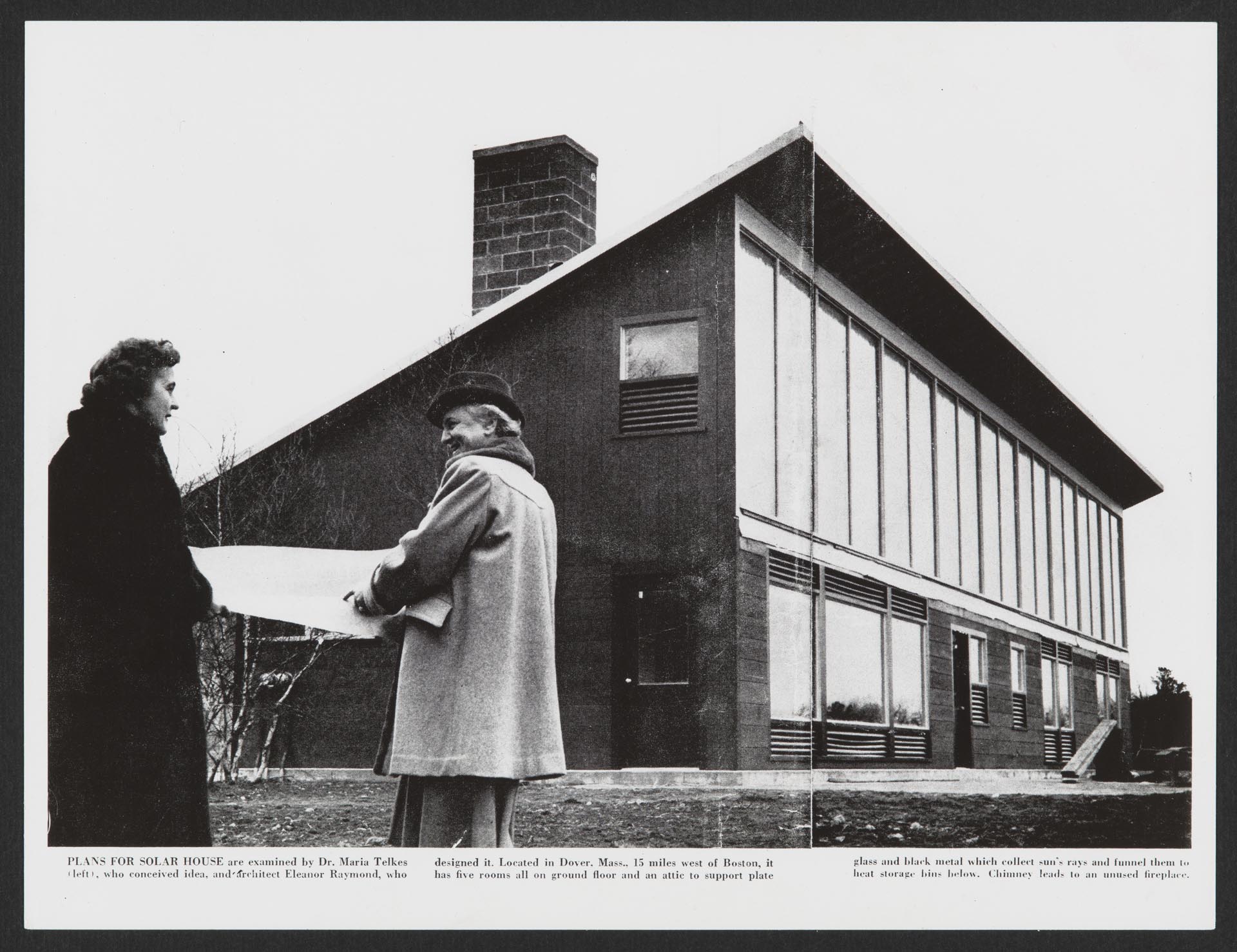

Maria Telkes, Dover Sun House, 1948

The biennial’s exhibition The Energy Show, at Het Niewe Instituut in Rotterdam, will trace humanity’s timeless fascination with the sun, as well as the design history of solar energy. “The Greek myth of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun, is a reminder that solar energy requires an element of risk-taking, which doesn’t always lead to positive consequences” says designer and exhibition’s curator Matylda Krzykowski, adding: “It’s not just about showcasing solar technology, but getting visitors to question themselves, their surroundings and their own energy use.”

Among the works included is the Dover Sun House, a private residence designed in 1948 by engineer Mária Telkes and architect Eleanor Raymond, where heat-collecting panels were used on the top-floor window façade. A speculative film by designer Alice Wong, commissioned for the exhibition, will envision a day in an exclusively solar-powered world. Studio Swine’s Solar Extruder (2011) uses solar energy to gather and melt discarded plastics from the ocean. Additionally, an open call for solar ideas from ordinary citizens will launch at Salone del Mobile in Milan in June.

The exhibition and the biennial will also consider the political aspects of energy transitions. The documentary Solar Mamas (2011) highlights the lives of women living in communities that are off the energy grid. “Experts say that solar technology isn’t more widespread because of the fossil fuel lobby,” says Krzykowski, pointing to different approaches to solar energy adopted by successive US presidents since Jimmy Carter. “It’s not just about the availability of solar technology, but about the people who make decisions. It needs human energy to be successful.”

As such, the biennial, which will travel to new cities for each edition, aims to encourage more grassroots approaches to solar energy. “We want to aim for a solar democracy, and not create the same problematic power structures around the access to energy that exist now,” concludes van Dongen.

The Latest

Things to Covet

Here are some stunning, locally designed products that have caught our eye

An Urban Wadi

Designed by Dutch architects Mecanoo, this new museum’s design echoes natural rock formations

Studio 971 Relaunches Its Sheikh Zayed Showroom

The showroom reopens as a refined, contemporary destination celebrating Italian craftsmanship, innovation, and timeless design.

Making Space

This book reclaims the narrative of women in interior design

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage