Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

The Ataturk Cultural Center in Istanbul reflects nearly a century of political and cultural development

Although recently reconstructed, the Ataturk Cultural Center in Istanbul has a long history that dates back to the late 1930s

Although recently reconstructed, the Ataturk Cultural Center in Istanbul has a long history that dates back to the late 1930s, when French urban planner and architect Henri Prost proposed a masterplan for the Turkish capital. In addition to suggesting the transformation of the city’s military barracks and surrounding cemetery into a park, the plan proposed the construction of an opera house in the historic Taksim Square. Prost also recommended Auguste Perret, the famous French architect behind Paris’ Champs-Elysees Theatre, to design it.

However, as World War II ravaged the continent, Perret was unable to finish the opera house, and his colleague Rükneddin Güney was commissioned to complete the project. Güney, along with partner Feridun Kip, laid the building foundation on 29 May 1946, during the reign of Istanbul governor and mayor Lütfi Kırdar. Yet, once again, the construction of the opera house was halted, and the project was handed over to the Ministry of Finance in July 1953, after which German architect Paul Bonatz took over and prepared sketches for the main stage and front façade.

With its reinforced colonnade using existing column axes, and its plinth with entrance steps in the middle, Bonatz’s design for the front-facing façade had a classical monumental expression, comparable to Perret’s Art Deco architecture. However, despite the updated architectural designs, the building remained unbuilt for decades, even as Istanbul witnessed periods of rapid construction.

By the late 1950s, though, Turkish architect Hayati Tabanlıoğlu returned from his studies in Hanover, Germany, and was appointed to oversee the development and construction of the opera house by the Ministry of Public Works. The building was reidentified as a cultural centre, and benefited from the cooperation of installation systems, stage techniques and acoustic experts. Hayati also applied the language and materials of modern architecture, including steel, concrete and glass. And though the construction of the building was again delayed due to lack of funds and a coup in 1960, it was finally completed in 1969, serving as one of the largest buildings of its kind in Turkey.

Inaugurated as the ‘Istanbul Cultural Palace’, the reinforced concrete structure featured a large foyer with a grand staircase, a main performance hall, and a large glass façade that faced the street. Throughout its first year, multiple artists took to the stage, such as French pianist Jean Fonda, British violinist Manoug Parikian and Turkish pianist Hülya Saydam, and the building quickly became an integral part of Istanbul life.

But in November 1970, during the performance of The Crucible, a devastating fire broke out due to a faulty projector. The fire damaged the entire stage as well as large sections of the auditorium. Reconstruction took seven years, and the building reopened in 1977 as the ‘Ataturk Cultural Center’.

Throughout its years, the Ataturk Cultural Center served as a symbol of Istanbul’s social, cultural and technological development. It reflected the city’s history in its narrative, construction and ultimate architectural language. It was a space for the Turkish people to enjoy the progressive expressions of their society, as well as observe Western artistic productions.

However, over the course of more than 50 years, the Ataturk Cultural Center slowly aged and weakened. And come the early 2000s, the building was handed over to award-winning Turkish architecture firm Tabanlıoğlu Architects, run by Hayati’s son Murat, and Melkan Tabanlıoğlu. The office was asked to consider restoration, as preserving the original structure was the favoured strategy. However, after conducting several studies, the office determined that the existing structure didn’t have the infrastructure required to meet the present-day demands of a modern opera house and cultural centre.

According to Melkan, the project needed to be reconstructed so it could integrate the complex stage systems and interspace relations required to ensure seamless acoustics and comfortable viewing angles, as well as to respond to the requirements of the newly added spaces. Simultaneously, the architects updated the ventilation, circulation and air conditioning systems of the building, as well as the lighting, electromechanics and auditorium layout.

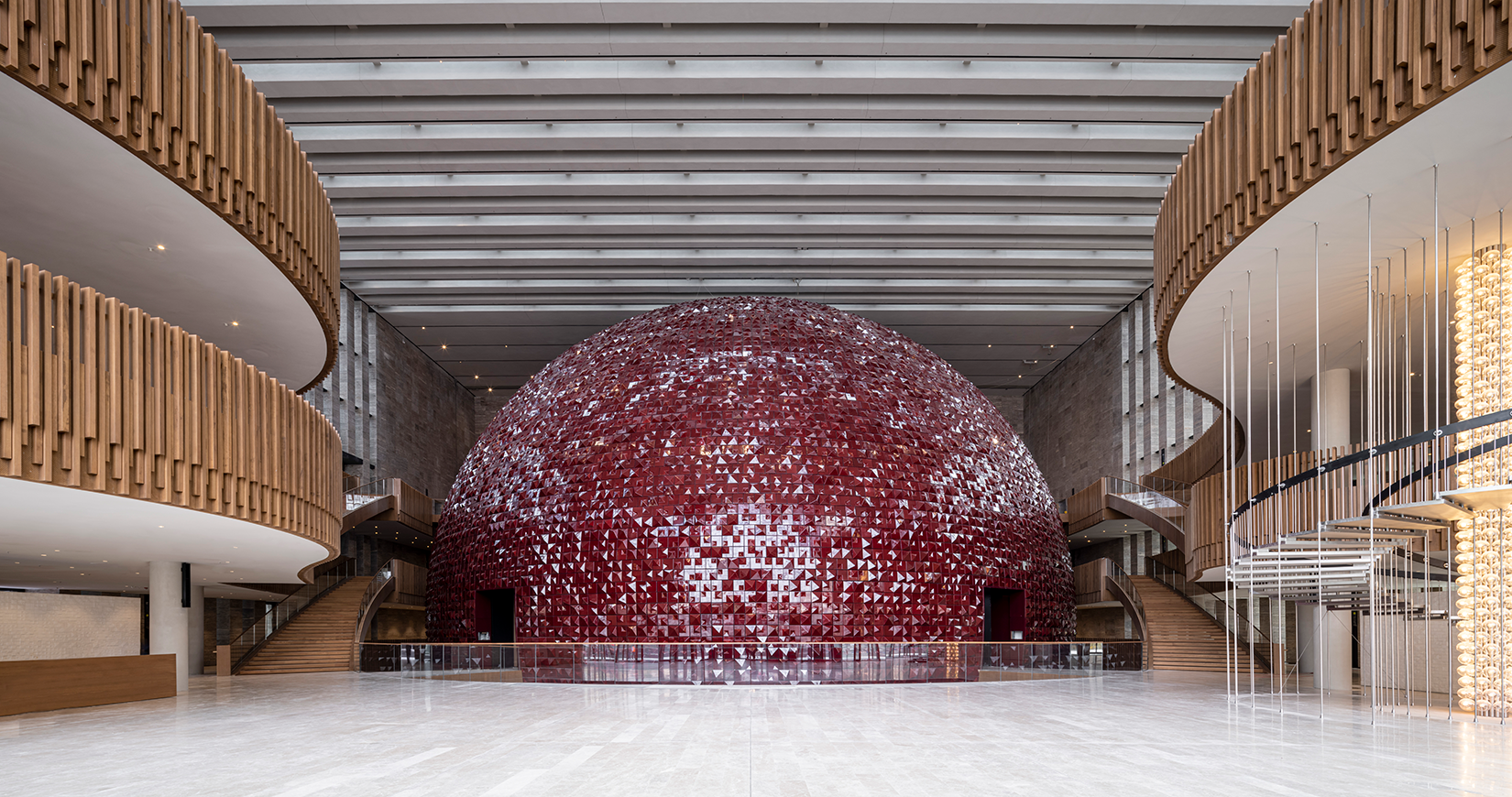

Today, the Ataturk Cultural Center features an opera house (contained within a large red sphere in the centre of the main hall), a gallery, music platform, library, children’s art centre, a multipurpose hall, cinema, restaurants and much more. And although many spaces have been added, throughout, the architecture draws a lot of inspiration from its former life, which is most evident in the façade, foyer and spiral staircase at the entrance.

According to Melkan, the design of the original glass façade, with its aluminium grid skin, was recreated for the new centre, as was the architectural form and mass of the building. The new structure also retains the transparent character of the old, which allows the outside and inside to blend together. Just beyond the entrance, too, a large, open and layered foyer welcomes visitors and allows panning views of the red dome in the centre, as well as of the large wooden stairway. Both the dome and the staircase bear references to Hayati’s design via materiality – the dome through the use of red ceramic tiles and the stairs through the use of wooden balustrades.

Elsewhere, a contemporary architectural language was applied, such as in the auditorium, offices and commercial spaces, where curved surfaces mix with clean lines and minimal ornamentation. By maintaining the familiarity of the original building while integrating a modern interpretation of the space, the Ataturk Cultural Center continues to serve as a legacy of the city’s creative, social and political development.

“The most important thing for us when creating this new centre – while using references to what was there before – was to design a contemporary continuation of Hayati’s work,” says Melkan. “We needed a balance. The building had to reflect today’s architectural approach while providing the same feeling to those visiting.”

Photography by Emre Dorter

The Latest

Maison Aimée Opens Its New Flagship Showroom

The Dubai-based design house opens its new showroom at the Kia building in Al Quoz.

Crafting Heritage: David and Nicolas on Abu Dhabi’s Equestrian Spaces

Inside the philosophy, collaboration, and vision behind the Equestrian Library and Saddle Workshop.

Contemporary Sensibilities, Historical Context

Mario Tsai takes us behind the making of his iconic piece – the Pagoda

Nebras Aljoaib Unveils a Passage Between Light and Stone

Between raw stone and responsive light, Riyadh steps into a space shaped by memory and momentum.

Reviving Heritage

Qasr Bin Kadsa in Baljurashi, Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia will be restored and reimagined as a boutique heritage hotel

Alserkal x Design Miami: A Cultural Bridge for Collectible Design

Alserkal and Design Miami announce one of a kind collaboration.

Minotticucine Opens its First Luxury Kitchen Showroom in Dubai

The brand will showcase its novelties at the Purity showroom in Dubai

Where Design Meets Experience

Fady Friberg has created a space that unites more than 70 brands under one roof, fostering community connection while delivering an experience unlike any other

Read ‘The Winner’s Issue’ – Note from the editor

Read the December issue now.

Art Dubai 2026 – What to Expect

The unveils new sections and global collaborations under new Director Dunja Gottweis.

‘One Nation’ Brings Art to Boxpark

A vibrant tribute to Emirati creativity.

In conversation with Karine Obegi and Mauro Nastri

We caught up with Karine Obegi, CEO of OBEGI Home and Mauro Nastri, Global Export Manager of Italian brand Porada, at their collaborative stand in Downtown Design.