Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Step inside the mystical world of Lebanese artist and designer Rumi Dalle

Rumi Dalle's designs sit on the verge of reality and imagination

There are numerous ways one can describe the work of Lebanese artist and designer Rumi Dalle, although many choose to settle on words like ‘fantastical’ or ‘otherworldly’. Perhaps it is the curious selection and combination of materials, her sensual compositions or even the daring forms that have the ability to spark both fascination and unease.

Photography by Tarek Moukaddem for identity

“I think the right word [for my work is] ‘timeless’. When you look at something that is timeless, it connects the past with the present and the future. That’s why it feels fantastical or otherworldly; it is ageless, you can’t put a date to it. It even feels alien,” Dalle muses. “It looks futuristic but also ancient; but to me, the right word is ‘timeless’.”

Photography by Tarek Moukaddem for identity

Dalle’s career began with designing window displays for retail outlets, which she says she appreciates as displaying art for the public, instead of in a gallery which not everyone is able to access. “Art should be everywhere; it should be on the street, it should be what you’re wearing; it should not be between closed halls in an all-white environment,” she says. “A window display is appreciated by everyone.”

Her first collaboration involved creating Magrabi Optical window displays for businesswoman and art patron Cherine Magrabi Tayeb. She then went on to design for Hermès in Beirut and Paris and is now a Hermès-certified designer, conceiving themes for its boutiques around the world.

Much of Dalle’s sensibility and approach to design stems from her childhood experiences and her observations about women in Lebanese society – including her mother. Dalle was born in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War which had left the country in tough circumstances, and many women were forced to take on domestic crafts such as sewing clothes for their families.

“I like to work with women who are not trained as professional artisans but who work out of their homes,” Dalle expIains. “I think this goes back to my childhood, to watching my mom for example, and how she started sewing clothes. It is craftsmanship that is born out of necessity and not out of luxury – and this fascinates me.”

As a child Dalle would create dolls from scraps that she found around the house, be it fabric or even tissue paper. “This goes back to the idea of using what’s around the house, which relates to recycling and sustainability. This is really how I started experimenting with materials and textures and surfaces – it all came out of necessity. Then, of course, I went on to design school and I wanted to reflect on that: being a child growing up in a lower-to-middle class family and looking back at those societies and those circumstances and really studying that. And stretching it into my work today. That’s really what I’m interested in.”

One of Dalle’s biggest collaborators to date is third-generation carpet gallery Iwan Maktabi, with whom she’s worked for 12 years. Their latest project, which was showcased at Nomad Circle this year, is called ‘It felt like a dream’ and comprises a collection of sculptural wall tapestries that are made from felt. The project is part of the gallery’s wider Iwan Maktabi Lab initiative which focuses on collaborations that drive and experiment with culture, creativity and craft.

For the collection, Dalle travelled to Konya in Turkey to meet a family of felt makers who for generations have devoted their craft to making felt rugs and kepeneks for shepherds, and who have restored the earliest sikkes of the dervishes which are now found in Mevlana Museum – the mausoleum of Jalal ad-Din Muhammed Rumi, the famous Sufi mystic and poet.

An unexpected turn of events led to Dalle instead collaborating with the wife of the master felt maker Mehmet, which absolutely transformed the experience for her. “I watched as a craft that has been dominated by men for centuries unfolded through the fingers and feeling of Theresa. It was the same material, yet handled in a more vulnerable and honest way, becoming more emotional and sensual, less dogmatic, more spiritual, still present and mindful,” the artist recounts.

In felting, as with many other centuries-old crafts, women often found themselves relegated to the home, to private spaces, while men were in the public eye, in workshops and felt-making saunas. The process of felting rugs centres on a man’s physical form, as it requires strength to carry the weight and agitate the wool.

“A lot of my work, when it comes to craft, is about the dynamics between men and women. My research looks at how crafts carried by women hold a special form of intimacy,” Dalle explains.

While her work is inspired by tradition and folklore, the intention is always to break the said tradition by focusing on memory and how that can be translated. “It’s more about playing on memory than focusing on the tradition of the crafts,” she explains. “I’m not interested in the craft itself as much as I am interested in the memory. I always have this problem with the person teaching me the craft, which is that I’m not here to just learn about a step-by-step process, I need to learn about the memory and the spirituality behind the craft and the storytelling, not only about the process. I, myself, can break the process and break the grid and recreate it.”

For Dalle, what is even more important than the craft is the material which precedes the craft and informs the entire process. “When I touch material, it has poetry to it. Material speaks; it’s like strata, it’s like skin, it’s not a dead object,” Dalle says. “Then I seek out the craft for that material. When you start to think of material as a living object, you realise that it is also timeless.”

Dalle’s latest project is designing the scenography of the Beirut Concept Store for this year’s Dubai Design Week, which consists of a 100-square metre space exhibiting the works of Lebanese designers. For this, the artist has collected linens from Lebanese families – some of which date back to the 1950s, others as recent as the Beirut Blast – resulting in an installation of over 1000 pillows called ‘The Dream’. “It’s really about composing a Lebanese dream. Most of the pillows were brought from houses of middle-to-lower class families, and the detailing on the pillows is amazing.”

The pillowcases are all used and have marks of wear and tear, and even burn marks. “People didn’t have money to spend on new pillow covers so what they did is spend hours and hours mending these pillows. And we are not talking about stitching; they actually removed the threads from the pillow and connected it with another thread. We call this ‘ratti’. It’s a technique of weaving which is usually done with very expensive rugs, not pillow covers. But imagine, people in Lebanon did it with pillow covers. That just gave me goosebumps,” Dalle says.

The installation is also about a country that is healing and mending itself, she adds. And while working as a designer in Lebanon has its many challenges – especially with the current crisis in the aftermath of the port explosion – Dalle insists that she will not leave her home country behind. “All of my work is inspired by the situation in Lebanon. I am very connected to my artisans; we are like family; I cannot leave them,” she says. “It is my workspace and my community. When your ship is sinking, you cannot just leave and let everyone else sink.”

The Latest

A New Standard in Coastal Luxury

La Perla redefines seaside living with hand-crafted interiors and timeless architecture

Things to Covet

Here are some stunning, locally designed products that have caught our eye

An Urban Wadi

Designed by Dutch architects Mecanoo, this new museum’s design echoes natural rock formations

Studio 971 Relaunches Its Sheikh Zayed Showroom

The showroom reopens as a refined, contemporary destination celebrating Italian craftsmanship, innovation, and timeless design.

Making Space

This book reclaims the narrative of women in interior design

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

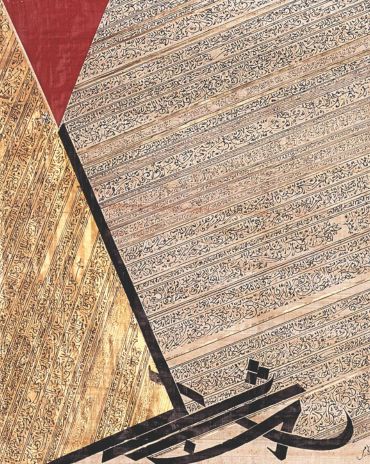

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.