Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Rana Begum shares her journey as an artist and gaining confidence in her craft

Rana Begum is one of the most in-demand artists of today

When Rana Begum arrived in the UK with her family, she was only six years old and didn’t speak a word of English. Drawing replaced language – something the British-Bangladeshi artist always struggled with. By the time she reached the end of her schooling, art was the only subject she was truly excelling at, although a lot of effort was put into persuading her family.

“My father realised how I wasn’t willing to give up on it, and how determined I was. When I applied for my BA, he knew I was nervous about how I was going to take all my work over for the interview. By then I had made a lot of sculptural work and things that you couldn’t just put in a portfolio. So, he actually hired a man with a van and surprised me. He was shocked when I sold my degree show. He couldn’t understand how I could possibly make any money from art. He came to the show just to see what it was that I do. He said, ‘anyone can make this’, she recalls, humourously. “He is no longer around,” Begum adds. “I wish he could see where I am now in my career.”

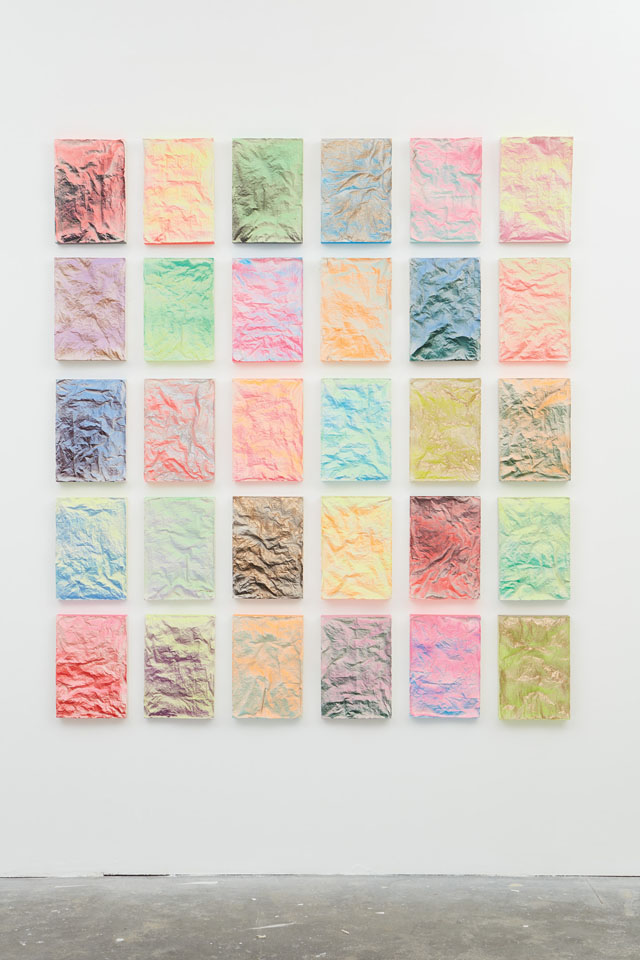

No. 901 Folded Grid, 2019. Photography by Philip White

Begum is currently one of the most in-demand artists whose works have been showcased in cities including London (where she now lives and works), Hong Kong and Dubai – where she was awarded the Abraaj Group Art Prize in 2017 as well as being represented by the Third Line Gallery in Alserkal Avenue, where her solo show, ‘Perception and Reflection’ took place in 2019.

Begum’s sculptural works combine abstract forms and geometry, using mostly industrial materials and a dose of spontaneity and motion, where a change of light in the environment could impact the form and the use of fluorescent colour. The viewer also plays a vital role in the work, who is encouraged to observe the pieces from multiple perspectives, gracing it with a transformational nature. The simplicity and geometry in Begum’s work is born from a number of influences – some which were, at first, subconscious. These range from the geometric patterns found in Islamic art and architecture to her upbringing that involved rituals of repetition such as praying five times a day and reading the Qur’an.

“What I am excited about is this kind of connection with the things that I see. The vibrant bold colours that you see in Islamic art and architecture and the bold use of geometry. The idea of the infinite. It all kind of stems from there and these are things that I am excited by. But I also still love the relevance that it has to now, and to my experiences.”

Begum’s childhood memories from Bangladesh have also inspired many of the principles that arise in her work, such as the honest yet ephemeral influence of light.

“It was through Cognitive Analytical Therapy that I realised that I spent a lot of my childhood in Bangladesh kind of just staring into space. I used to stare at the water quite a lot, watching the reflections and the light changing. I also used to stare at the rice fields. Just rows and rows of rice fields and watching the movements of the plants. And that’s when it hit me. I was like, ‘my God, it kind of makes sense now’.”

However, Begum explains that despite the struggle, she did not want to be defined by her background: “I was really keen to keep the doors open and not be pigeonholed. As much as I was struggling as a female Muslim artist, I was determined to not go down that road. I wanted the work to naturally develop and find its position in the art world,” she says.

Begum began working with figurative and representational art although her works already possessed some of the elements she is known for today. Discovering constructivist and abstract artists such as Donald Judd, Sol Le Witt, Agnes Martin and Kenneth Martin allowed her to visualise the potential and growth of her own work.

Is she comfortable being labeled a minimalist? “There has always been this thing where people have to attach a label and I have always tried to stay away from that. But I feel that people need some kind of anchor and I think minimalist is the closest to what I am trying to do, so for me it hasn’t been a problem,” she says.

No. 764 Baskets, 2017-18. Photography by Paul Allitt

On the other hand, she does not agree when her work is described as ‘illusionary’: “I have an issue with the word ‘illusion’ because I feel that that is not something that I am trying to do with my work. It’s never been about deceiving the viewer. It is honest in terms of the material I use and how it is used as well,” she says.

Begum’s research initially began with form and light and only in 2008 was she able to introduce colour into her work. She realised she couldn’t do it all at once and needed to separate them in order to bring them together eventually.

“I really struggled with colour. You wouldn’t think that, but, I definitely struggled with colour and that’s why I wanted to spend time to understand colour a bit more. Now I feel more confident and I can work with colour a lot better than I used to.

“I feel like now, form, light and colour are points that create this triangle [in my work] and one can’t work without the other. I knew, before, that I wasn’t quite there yet. I knew that I wasn’t achieving what I wanted to. The earlier work helped me understand something I didn’t understand at first. I needed to go through that process,” she explains.

“I was really keen to keep the doors open and not be pigeonholed. As much as I was struggling as a female Muslim artist, I was determined to not go down that road. I wanted the work to naturally develop and find its position in the art world.”

Begum’s solo exhibition, ‘The Space Between’ at the Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art in London in 2016, curated by the foundation’s founder and director, Ziba Ardalan, allowed Begum to achieve a greater sense of understanding of her work as it brought together a selection of past and recent works in a manner that was “slightly chronological”.

“It really helped bring things together and make sense of what I am doing. The Parasol Unit exhibition gave me the confidence that I needed,” Begum shares.

No. 673 M Drawing, 2016

She is also beginning to create more affordable works. “A lot of the work that I do goes into collectors’ homes. But I have started doing prints and working with Cristea Roberts Gallery and those pieces are more accessible. I think that is important,” she says.

Begum has also recently contributed to the NHS 100 Rooms initiative, her work now gracing the walls of the respite rooms for frontline workers in hospitals across east London.

“I have spent a lot of time at the hospitals because my father was quite ill, and he was in and out of hospitals for years. And I know we really valued the artworks that were in the waiting room or in the hallway. It made a massive difference to us. For me knowing that the art makes a difference to your mental health was a big deal,” she says.

“In these times of COVID-19, you have to do what you can. It’s not easy. The best thing is to know that the art can make a difference.”

The Latest

Maison Aimée Opens Its New Flagship Showroom

The Dubai-based design house opens its new showroom at the Kia building in Al Quoz.

Crafting Heritage: David and Nicolas on Abu Dhabi’s Equestrian Spaces

Inside the philosophy, collaboration, and vision behind the Equestrian Library and Saddle Workshop.

Contemporary Sensibilities, Historical Context

Mario Tsai takes us behind the making of his iconic piece – the Pagoda

Nebras Aljoaib Unveils a Passage Between Light and Stone

Between raw stone and responsive light, Riyadh steps into a space shaped by memory and momentum.

Reviving Heritage

Qasr Bin Kadsa in Baljurashi, Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia will be restored and reimagined as a boutique heritage hotel

Alserkal x Design Miami: A Cultural Bridge for Collectible Design

Alserkal and Design Miami announce one of a kind collaboration.

Minotticucine Opens its First Luxury Kitchen Showroom in Dubai

The brand will showcase its novelties at the Purity showroom in Dubai

Where Design Meets Experience

Fady Friberg has created a space that unites more than 70 brands under one roof, fostering community connection while delivering an experience unlike any other

Read ‘The Winner’s Issue’ – Note from the editor

Read the December issue now.

Art Dubai 2026 – What to Expect

The unveils new sections and global collaborations under new Director Dunja Gottweis.

‘One Nation’ Brings Art to Boxpark

A vibrant tribute to Emirati creativity.

In conversation with Karine Obegi and Mauro Nastri

We caught up with Karine Obegi, CEO of OBEGI Home and Mauro Nastri, Global Export Manager of Italian brand Porada, at their collaborative stand in Downtown Design.