Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Lebanon’s expatriate designers are working to keep local craftsmanship alive in their home country

identity speaks to Lebanese designers about the role artisanship plays in their work

Beirut’s buoyant creative industry has produced many of the region’s most important designers. But a succession of financial and political crises in Lebanon, including the explosion at the Beirut Port in August 2020, caused many of the city’s designers to emigrate.

“It was hard to be creative in Lebanon. The people were losing their spirit. We were living with limited fuel, electricity and water,” says Rami Boushdid, founder of Beirut-based Studio Caramel, a design studio known for its handmade, luxury bar carts. A year ago, propelled by the crisis, Boushdid moved to Paris, where he set up the French arm of Studio Caramel. “In order to grow as a company we had to set up a base in Europe,” he explains.

But the production, he adds, remains in Lebanon. Boushdid is one of many Lebanese designers seeking new bases abroad, while continuing to work with local Lebanese craftsmen. Together, they produce objects in wood, metal, stone and other traditional materials. “Lebanon is where it all started; it’s where the products are made, it’s part of who we are and part of our traditions,” he says.

Among those spending more time in the UAE is designer Nada Debs, founder of her eponymous studio in Beirut. “Dubai was the next natural step. We have a lot of clients here, and the emirate is a regional and international hub,” says the studio’s business manager, Tamer Khatib.

But Debs, like many others, is adamant that the studio’s production remains in Lebanon. “Our vision and goal has always been to support Lebanese craft. The challenges that we face in return are what made us a studio,” says Khatib. “Our studio is still in Beirut, and employs over 20 people, excluding the artisans that we also work with. We’re here to stay.”

Part of many designers’ reasons to continue to keep close ties with Lebanon is due to the long-standing relationships that they have developed with local Lebanese craftsmen. “I’ve been working with the same artisans for years,” says Thomas Trad, a Lebanese product designer who recently moved to Dubai. “Not only do they have exceptional skill, but they’re eager to learn contemporary techniques, which creates a beautiful dialogue between the designer and the craftsmen. It has helped me improve my own designs.”

Trad’s most recent projects in the UAE, including a collaboration with Lebanese carpet maker Iwan Maktabi in Dubai, have been entirely produced in Lebanon. “Dubai is a great place to meet people from different backgrounds and from all over the world,” he says. “There have been new opportunities here, yet I still want to support Lebanese craftsmen.” Trad’s newest series includes handmade marble vases, and a hand-carved wooden table in a low-lying Japanese style with a gouged surface. “The wood carver was trained in more traditional carving techniques, but we were able to work together to produce a modern gouged surface,” Trad says of his collaboration with the artisan.

Often, these relationships between designers and craftsmen have been key to the development of many Lebanese design studios. Jeweller Alexandra Hakim has been based in Madrid, the Spanish capital, for the past two years. A maker herself, Hakim first set up shop in the Bourj Hammoud district of Beirut, which is known for its fine jewellers. “I walked around the area looking for somebody who would integrate me into their studio and let me do my own thing,” she recalls. Eventually, she was taken in by Ajemian, a local jeweller and workshop owner.

But building trust took years. “In Lebanon, women don’t make jewellery; the artisans are usually male,” she says. “So, Ajemian tested me at the beginning. He took [my presence in his studio] as a joke.” Hakim’s contemporary approach involves casting found objects and waste products into jewellery. This often clashed with the techniques of more traditionally trained craftsmen in Ajemian’s studio. “I had to tweak what I could work with,” she explains, “but once Ajemian trusted me, I was able to train his artisans to make things the way I wanted them.”

Designers insist that the quality of craftsmanship in Lebanon is unrivalled in the region, which compels them to keep producing there. “We’re working with highly specialised crafts like marquetry and mother of pearl inlay,” says Khatib of the work at Studio Nada Debs. “We’ve yet to find the same approach to craft elsewhere.”

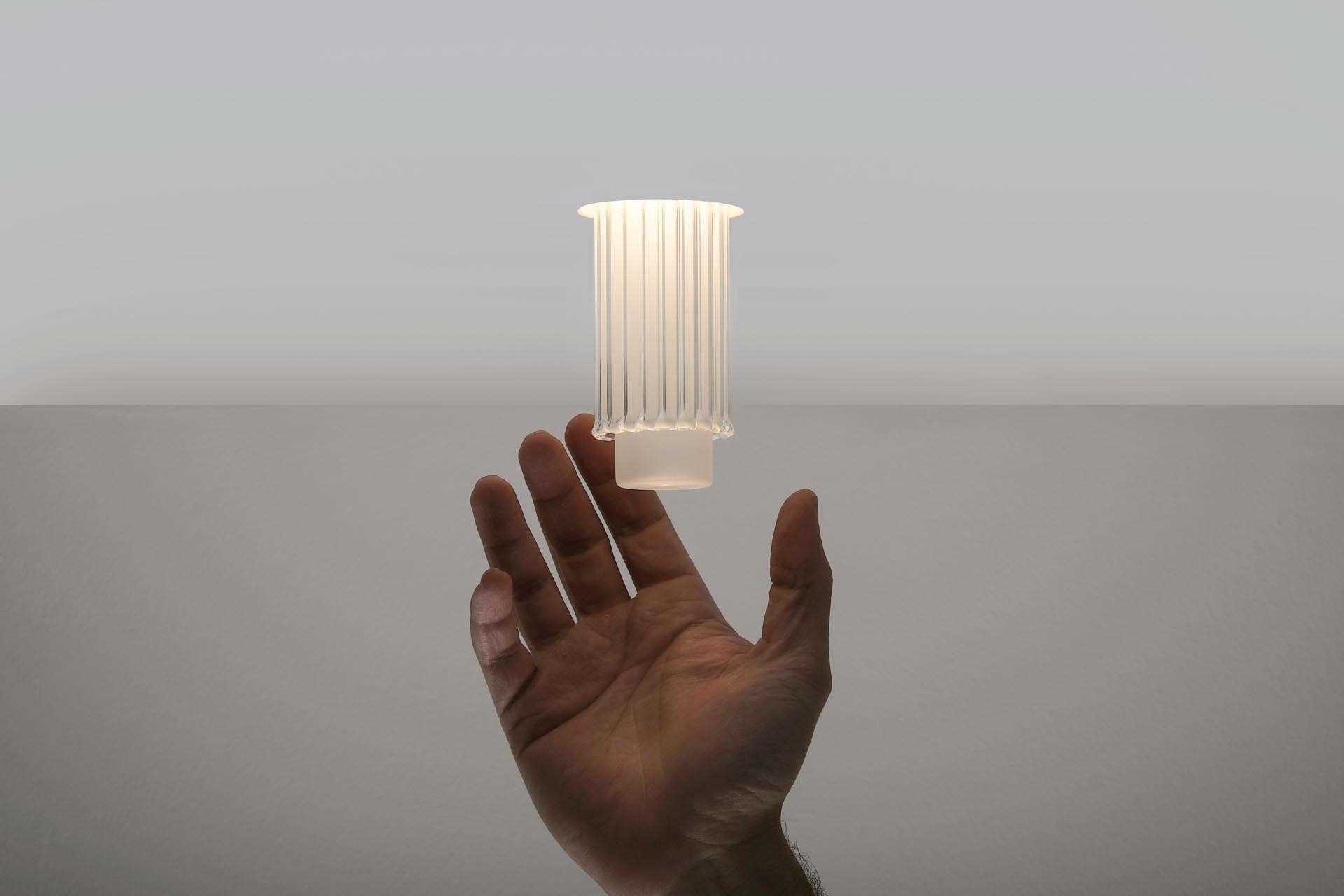

And, in a small country like Lebanon, it is not difficult to gain access to a diverse range of crafts and workshops. Samer Saadeh, founder of Fabraca Studios, creates bespoke lighting and architectural solutions using traditional metalwork and other locally available techniques. He works in Beirut’s industrial quarter in Sed Bouchrieh, which is home to many of the city’s workshops.

“It’s like a giant toy store, with so many different types of craft so close to each other,” he describes.

In light of the financial and political crisis in Lebanon, Saadeh has focused on overseas projects that can help promote the industry. Among these is designing lighting solutions for the Emirates Palace hotel in Dubai, a currently ongoing project. “I wanted to show that you can still have this exclusive and beautiful detailing and production from Lebanese artisans,” he says. Yet he also notes an increased demand in Lebanon for locally made products. “The crisis has been a big slap in the face for people who previously relied on imports,” he says.

What makes Lebanon’s crafts industry, Saadeh adds, is its historic roots. “A lot of the craftsmen in the industrial city were Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire, and they brought their craft with them,” he says. What’s more, Lebanon’s craftsmen held an important regional reputation in the 1960s and ‘70s. “The older artisans of the industrial city recalled to me how people would come all the way from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia or Jordan to have their furniture made in Lebanon,” he says.

Retaining a base in Lebanon, designers add, is also important for a brand’s identity. “Beirut was a good source of inspiration for the way I work,” Hakim explains. “There’s a charm to almost everything like the cafes, the streets, the restaurants, the graffiti [and even] the rubbish.”

For Boushdid, Lebanon’s hospitality scene, with its vibrant bars and restaurants, helped shape the direction of his studio. “In Lebanon, it’s important to think about your guests. Our culture brings people together. We didn’t learn about hospitality, we lived it. It may be the reason that we make bar carts.” he says. Indeed, many of Lebanon’s most famous architects made their mark in Beirut by designing restaurants and nightclubs.

Yet today, producing in Lebanon is fraught with challenges. Khatib recalls how fuel and electricity shortages in the past year hampered the studio’s production. “We are working with artisans all across the country, so getting the different parts and materials to them was tricky,” he says. Others have struggled with the long distance. “The production process is the stage that I love best,” says Trad, “so I miss being in Lebanon and visiting the workshops.”

While the industry continues to produce at a high quality, it is also fragile. “Many of the craftsmen became unemployed, and they didn’t teach their skills to their children,” says Saadeh, who witnessed the closure of a workshop employing dozens of artisans. Meanwhile, emigration continues to shrink the pool of available talent and craftsmanship. Both in the industrial quarter of Sed Bouchrieh and the jewellery district of Bourj Hammoud, local artisans and their families have been migrating out of Lebanon.

Nonetheless, Lebanese designers are determined to continue, whatever the cost. “I have suggested to Nada [Debs] that it would be easier to produce abroad, but she immediately reminds me of our mission to support local craftsmanship,” Khatib shares. And, in a bold move, Studio Caramel plans to launch a more accessible range of bar carts later in the year. This would see its production increase tenfold from 10 or 15 bespoke bar carts a year, to up to 200. “Of course, we have a plan B and a plan C,” says Boushdid, citing production in countries like Portugal or Italy, whose advantages are scalability, easier distribution routes to Europe and, in some cases, lower costs. “But for now, our aim is to produce entirely in Lebanon.”

The Latest

Turkish furniture house BYKEPI opens its first flagship in Dubai

Located in the Art of Living, the new BYKEPI store adds to the brand's international expansion.

Yla launches Audace – where metal transforms into sculptural elegance

The UAE-based luxury furniture atelier reimagines the role of metal in interior design through its inaugural collection.

Step inside Al Huzaifa Design Studio’s latest project

The studio has announced the completion of a bespoke holiday villa project in Fujairah.

Soulful Sanctuary

We take you inside a British design duo’s Tulum vacation home

A Sculptural Ode to the Sea

Designed by Killa Design, this bold architectural statement captures the spirit of superyachts and sustainability, and the evolution of Dubai’s coastline

Elevate Your Reading Space

Assouline’s new objects and home fragrances collection are an ideal complement to your reading rituals

All Aboard

What it will be like aboard the world’s largest residential yacht, the ULYSSIA?

Inside The Charleston

A tribute to Galle Fort’s complex heritage, The Charleston blends Art Deco elegance with Sri Lankan artistry and Bawa-infused modernism

Design Take: Buddha Bar

We unveil the story behind the iconic design of the much-loved Buddha Bar in Grosvenor House.

A Layered Narrative

An Edwardian home in London becomes a serene gallery of culture, craft and contemporary design

A Brand Symphony

Kader Mithani, CEO of Casamia, and Gian Luca Gessi, CEO of Gessi, reflect on the partnership between the two brands

The Art of Wellness

Kintsugi in Abu Dhabi, situated in a seven-storey villa, offers the ultimate zen retreat