Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh on creating ‘humane’ architecture

Lina Ghotmeh speaks about how architecture can be used to reflect on the past and inform the present

Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh creates buildings that embody the human experience – “living organisms” that react, breathe and ask questions – while in constant dialogue with their surroundings. With works spanning across Japan, France, Estonia and her hometown of Beirut, Ghotmeh speaks to identity about the power of architecture to reflect on the past in order to inform the present.

Can you tell us about growing up in Beirut – did your impressions of the city impact the way you approach architecture today?

Growing up in Beirut left a great mark on my approach to architecture, but also guided my interest in the field in the first place. Beirut is an open archaeology, layered both horizontally and vertically — layers of history and civilisations are constantly unveiled at the start of many constructions. The urban fabric of the city is a direct expression of its inhabitants’ diverse culture. Spatially, it is the city of possibilities and alternatives. Spaces are in constant negotiation with the environment, always revealing very interesting architectural conditions; diverse architectural identities, expressive in their textures, porous through their envelopes and inhabited by an organically growing nature. There is an intensity of life that transpires out of some of these conditions (human, material and natural), one that I always seek in the designs I create with my atelier.

Stone Garden in Beirut. Photography by Laurian-Ghinitoiu.

Tell us about your interest in archaeology and how that is reflected in your work.

I see the built landscape as a breathing body, one that retains the effects of human activity and reacts to them. Every design or every architecture by my atelier is constructed as an emergence, a discovery, even if built anew. Like a palimpsest, scribbled with many narratives (past, present or future), where nothing exists ex nihilo. Every new project is an original, innovative figure shedding a new perspective on a déjà là. This is what I refer to as the ‘Archaeology of the Future’, a projection of our roots into a desirable yet sustainable future; interventions embark my practice into a thorough research, like a detective’s work. We build what resembles a cabinet of curiosities for every project; we look back at ‘traces’ and ‘clues’, [and] actively channel them into newness.

What is the role of architecture for you and how do you aim to apply this approach within your own projects?

[It’s about] elevating the present, making our environment desirable and orchestrating new positive relations. Expressing the essence of what is there, or what precedes, expressing the essence of the materials in use by our designs, engineering the DNA of present ecosystems. Staying in touch and exalting the contexts our architectures live in and, by nature, affect — be it physically, ecologically or anthropologically. In this sense, I see architecture as a living organism, reacting to its surrounding, breathing symbiotically with it, asking questions. Animate rather than inanimate.

Photography by Iwaan Baan.

How important is context for an architectural project?

Understanding ‘context’ as the environment, the ‘milieu’ — physical or not — that we are integrating and interacting with, is a major aspect of everything I create as an architect. Architecture has a great responsibility towards its context. It is our duty to assess and be aware of the impact of our work on the framework we intervene in. The quality of the spaces we create has a direct impact on people’s wellbeing. On another level, architecture is also the physical expression of humans’ intellectual achievement; it contributes greatly to shaping human culture, serving as an activator of this constant state of evolution. Every ‘architecture’ is a process that requires time, thought and empathy.

Ateliers Hermès © Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture

Can you tell us about the significance of Stone Garden – both in terms of its architecture and what is communicates, but also as your first project in the Middle East and your hometown of Beirut?

Stone Garden was born out of a need to reconcile the human body, nature and the built scape. It is a project that asks multiple questions. Whether related to memory and identity, or to the place we give nature in our built environment, it takes a particular stake towards contemporary architecture. The setting of the building traces vertically the exact boundaries of its site – it chooses to embrace its neighbours instead of rising as a solo cube. Its shape reflects on the invisible building regulations that influence the built scape of our cities, as its angled geometry manifests various setback lines. Windows of different sizes are drawn in continuity to the organic fenestrations seen within neighbouring buildings. Varying in size, they house gardens, planters, flowerpots, include nature as part of our urban habitat and offer, at every level, an individualisation of the apartments. In Beirut, the building echoes specific figures that shape the city’s collective memory: the famous Pigeons’ Rock, the many buildings left derelict, the colour of Beirut’s uncovered earth.

ENM © Lina Ghotmeh and © Dorell.Ghotmeh.Tane © Takuji Shimmura

Can you talk about the choice of building envelope finish in the project, and the sense of craftsmanship that lends the human touch – what were your intentions here?

By having artisans hand-chisel the façade, I wanted to allow this sort of ‘imprint of the hand’, this memory of the human body, to add itself to Beirut’s ‘open archaeology’. Like in the sonnet Ozymandias, architecture is an art that stands the test of time — I wanted it to be permeated by our current history, by the current state of our art and our philosophy. The whole building envelope was combed in an artisanal way, as if combing earth to render it more fertile. The process of making this façade felt like a collective healing process, a kind of construction of a vertical inhabitable archaeology.

House in Japan © Dorell.Ghotmeh.Tane © Takumi Ota

We had spoken about this before, but it sadly seems like a kind of déjà vu that your first project in the region survived such a horrible incident with the Beirut blast, while a lot of your architecture reflects on the destruction of the Lebanese civil war. Almost a year later, how do you look back at this?

It was uncanny to experience the devastation caused by the blast almost exactly at the time I had been preparing to deliver Stone Garden. Strangely enough, the event revealed the inherent tale and structure behind the architecture of this tower. Located just a mile away from the explosion, the building’s architectural essence — the structure, the gardens — stood unshaken while the glass got completely blown away. When I went to see the building the day after the event, it felt like I was experiencing the narrative of the building: the past met the present and rendered the future timeless. There was a strange sense of suspension in time. I strongly felt the sense of the milieu and what architecture could say in such a context.

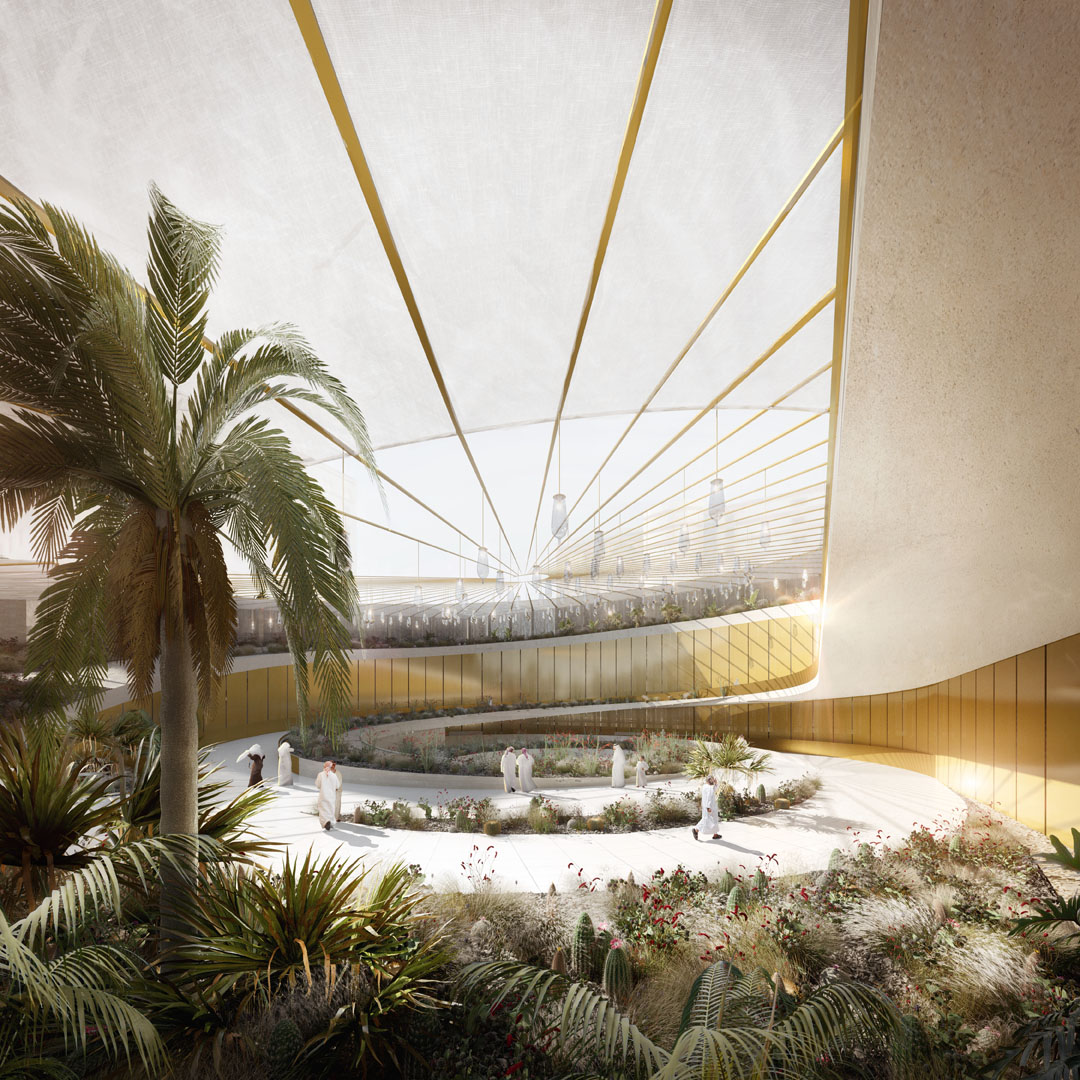

Museum of Creation © Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture

Can you talk more about creating human-centric architecture? Why is this important to you?

I would not call it human-centric architecture exactly, but would rather say I look for a humane architecture, one that is able to render beauty accessible to all: an architecture that invites the hand to touch, the body to wander and the spirit to flee. An architecture that can bring us closer to each other, to remind us of how connected we are to our environments. As humans, we are part of nature, we are constituted by nature. Thinking of a humane architecture is striving to break the schism between human and nature: aspiring for a more symbiotic, humble way to inhabit our planet.

Museum of Creation © Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture

What are some of the projects that you’re currently working on?

Currently among our projects is our construction of the Hermès Louviers Workshops in Normandy, a project I designed with my atelier, holding very high sustainable ambitions — a low-CO2, passive building. The project is made with hand-crafted artisanal bricks and sits calmly in dialogue with its surrounding landscape. Exploring the dancing body and the city, I am also working on the design of the National Choreographic Centre in Tours, [which is] meant to be completed in the coming couple of years. Worth mentioning lastly is a private museum and a house for an art collector in Europe, among others.

The Latest

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.

Asterite by Roula Salamoun

Capturing a moment of natural order, Asterite gathers elemental fragments into a grounded formation.

Maison Aimée Opens Its New Flagship Showroom

The Dubai-based design house opens its new showroom at the Kia building in Al Quoz.

Crafting Heritage: David and Nicolas on Abu Dhabi’s Equestrian Spaces

Inside the philosophy, collaboration, and vision behind the Equestrian Library and Saddle Workshop.

Contemporary Sensibilities, Historical Context

Mario Tsai takes us behind the making of his iconic piece – the Pagoda

Nebras Aljoaib Unveils a Passage Between Light and Stone

Between raw stone and responsive light, Riyadh steps into a space shaped by memory and momentum.

Reviving Heritage

Qasr Bin Kadsa in Baljurashi, Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia will be restored and reimagined as a boutique heritage hotel

Alserkal x Design Miami: A Cultural Bridge for Collectible Design

Alserkal and Design Miami announce one of a kind collaboration.

Minotticucine Opens its First Luxury Kitchen Showroom in Dubai

The brand will showcase its novelties at the Purity showroom in Dubai