Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Beirut-based Fabraca is using lighting design to push the city’s metalwork craft in a contemporary direction

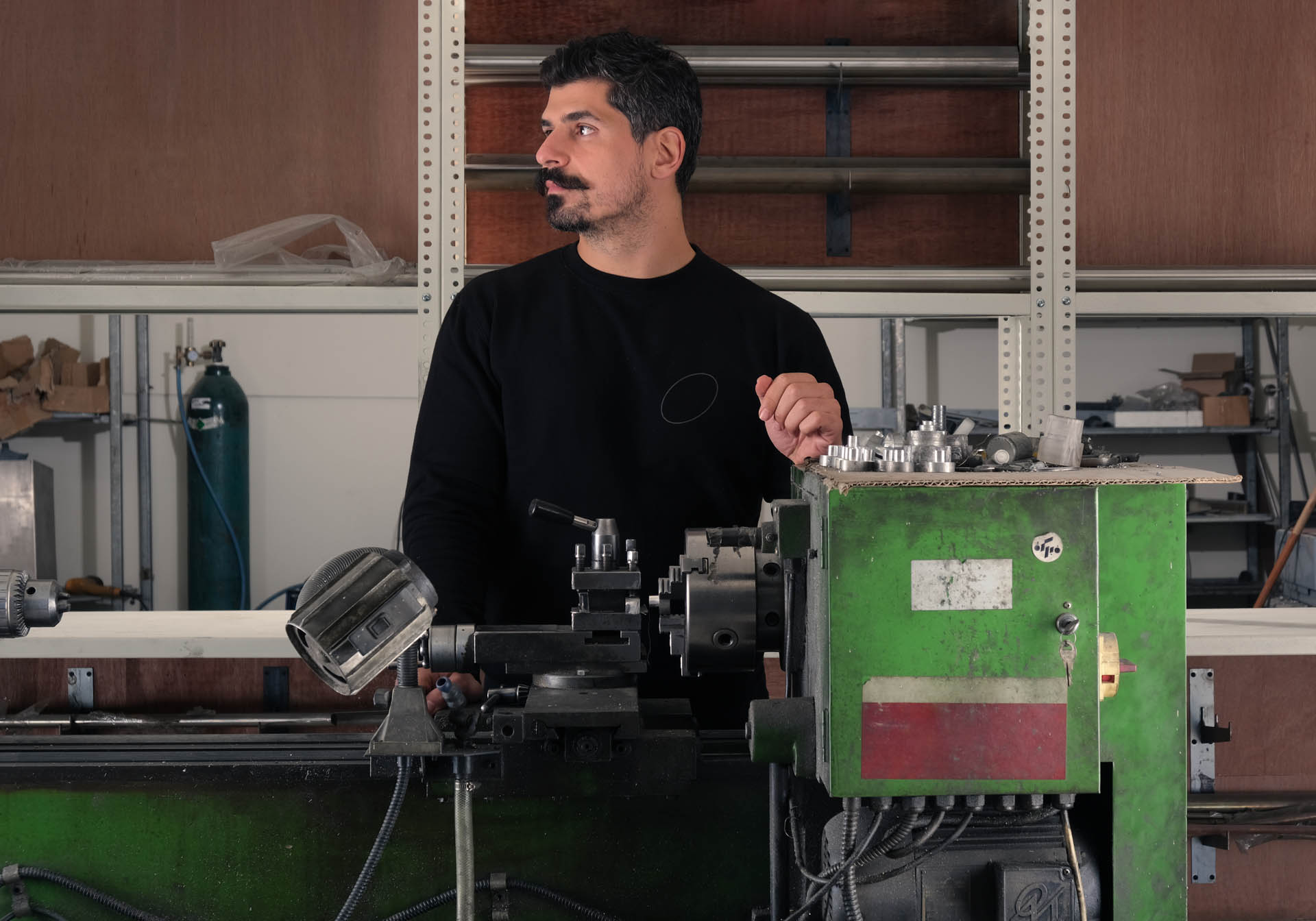

Founded by Samer Saadeh, Fabraca is contributing to preserving local craft in Lebanon

For Samer Saadeh, craftsmanship can contribute to more than just heritage, nostalgia and collectible objects. Since he founded his studio in Beirut in 2018, the architect-turned-lighting designer has shown that crafts can play a role in highly functional contemporary design solutions. “Lighting is needed for every project. We’re offering lighting solutions to solve a problem,” he says, contrasting this to the more decorative approaches to crafts.

His studio, Fabraca, is nestled in Sed Bouchrieh, Beirut’s industrial quarter which is home to many of the city’s craftsmen, whose specialisms range from metalwork to carpentry and textiles. From there, he works with a team of 12 craftsmen, mechanical engineers and architects on lighting projects in Lebanon and overseas, including the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and the development of Qasr al Hosn in Abu Dhabi. “People tend to think that artisans and craftsmanship are dying out because of the ways in which we use technology and mass production in design,” he says. “But the marriage between computer-generated designs and artisanal work is possible.”

Among his more recent designs, ‘Light Impact’ (2022) is a contemporary rendition of the chandelier that mimics the fluid movement of a rope. It was designed for Karim Bekdache Studio, an architectural practice overlooking the Beirut port, to replace a blown glass collectible chandelier that had shattered during the August 4th explosion.

“We tried to achieve the elegance of a chandelier with something as strong and robust as aluminium,” Saadeh explains. The lighting frame is composed of modular aluminium cylinders that are connected by a spherical joint. “The mechanisms connecting one piece and the other achieve this rope-like effect. If another blast were to happen, the piece would withstand the shock because it is so flexible.”

Each of the aluminium cylinders and connecting joints was hand-made in Fabraca’s studio. Saadeh developed the design with a team that includes mechanical engineers and metalworkers. “The engineering part that connects the pieces was computer-generated. We drew everything on a programme before going on to prototyping and going to the artisans with our drawings,” he shares.

Functionality is key to Fabraca’s approach. The studio’s latest project, ‘Belt Track’ (2022), is a series of manually adjustable and attachable lighting frames which was developed for Qasr Al Hosn’s upcoming cooking school at Erth. For this, Saadeh created lighting frames that are strapped onto the building’s air conditioning vents pipes. “Air conditioning vents exist in every indoor space in the UAE. We tried to clean up the ceiling by integrating the lighting and ventilation layers,” he explains. “Now you have less visible wiring, and a minimalist treatment of the ceiling.” The model is flexible and easily scalable to fit the size of the space. “This gives the architect or the user a lot of flexibility,” he adds.

Saadeh sees it as Fabraca’s mission to support local Lebanese craftsmanship, at a time when the country is experiencing economic and political collapse. He first encountered the industrious but fragile world of Beirut’s craftsmen in 2013, when he was freelancing from a metalworks factory. “The artisans could produce such exclusive and beautiful detailing, but they weren’t updating their product. They were still making things in the baroque style,” he says. “They hadn’t passed on the craft to their children. I really felt like we were losing these crafts.”

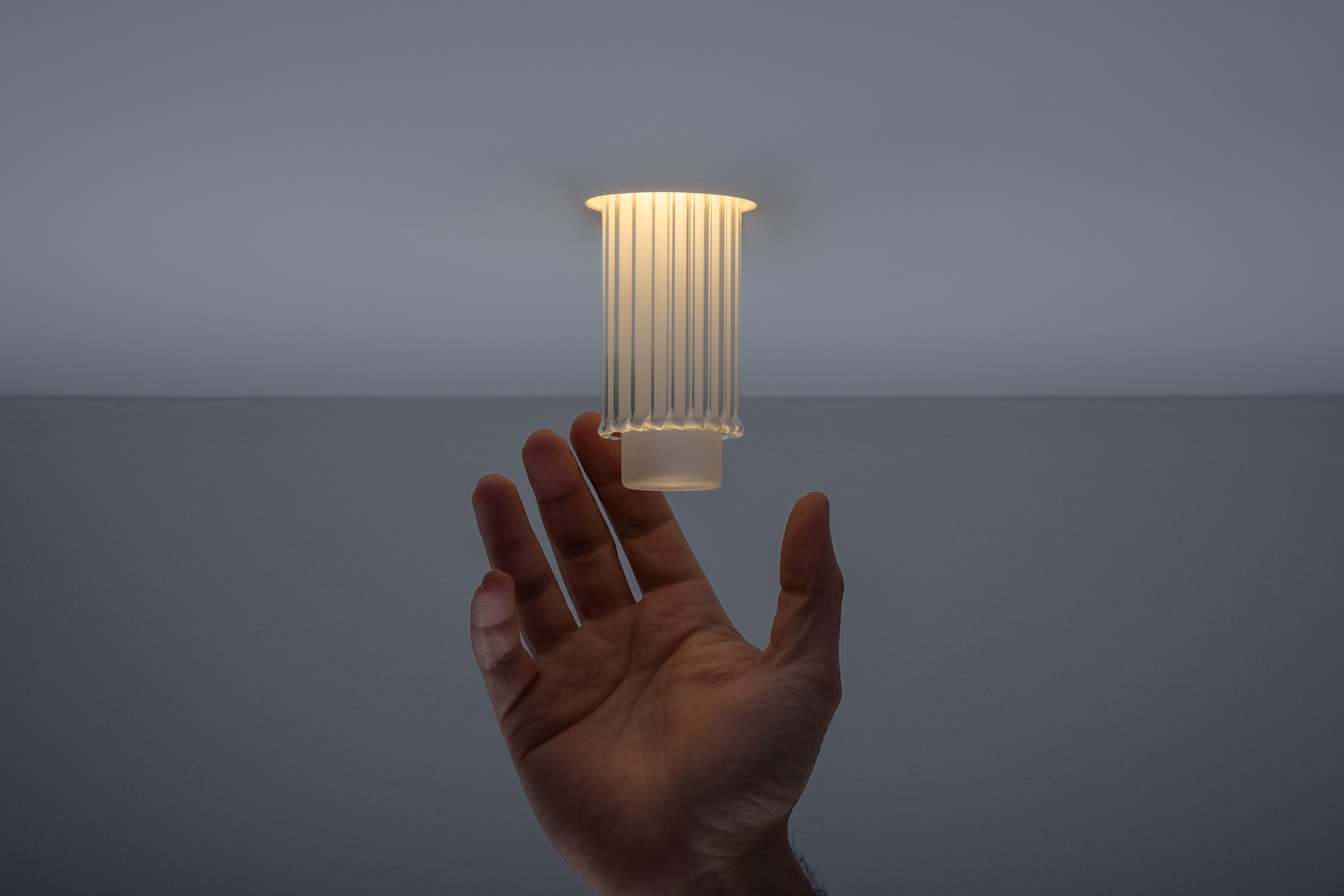

When he established his own studio in 2018, he recruited many of these craftsmen, who had been left jobless after the factory’s closure. Today, he employs a small team of metalworkers from the area and is also producing leather and blown glass products. His Jellyfish collection of mouth-blown glass light bulbs uses two layers of ribbed and tinted glass. Saddle, a wall-mounted light with a cone-shaped lampshade, was developed for a restaurant in Abu Dhabi, and includes a braided leather handle that allows the lamp to rotate.

While Saadeh insists that his approach to crafts is forward-thinking, he nonetheless values the historical roots of the trade. Fabraca’s emphasis on design solutions, functionality and a contemporary aesthetic, he argues, challenges dominant ideas around artisanship. “We’re not just producing limited edition collectibles,” he says. “I want to show that craftsmanship can be used in a much broader way, but we need to keep it ongoing and relatable.”

The Latest

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.