Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Bahraini artist Rashid Al Khalifa transforms childhood home into art museum

The Rashid Al Khalifa Art Foundation also houses the artist's private art collection

Bahraini artist and collector Rashid Al Khalifa once dreamt of becoming an architect. Though he never pursued his interest professionally, today he is actively contributing to the Gulf island’s architecture and design scenes.

In 2020, he launched the Rashid Al Khalifa Art Foundation, opening up his historic family home and private art collection to the public. “I hope it can be a place where people are inspired and encouraged to pursue their interests in art and architecture,” he says.

Earlier this year the RAK Art Foundation announced the inaugural edition of its architecture prize, aimed at architecture graduates from Bahrain. The winning entry will have the opportunity to design a new performing arts centre in Adhami – set outside of the capital of Manama – in addition to a cash prize.

The RAK Foundation is located in the town of Riffa, in the centre of the island. The original premises were built in the 1920s and are typical of Bahrain’s vanishing vernacular architecture: low-rising homes built of gypsum and lime, timber beams imported from maritime routes on the Arabian Sea, and a colonnaded central courtyard.

Al Khalifa is a member of the Bahraini royal family, and the historic townhouse was one of the first homes in the area. “Riffa is not as old as Manama or Muharraq; it was inhabited just over a hundred years ago. And because of its distance from the coastline, the conditions must have been very harsh, with a scarcity of water,” he contemplates.

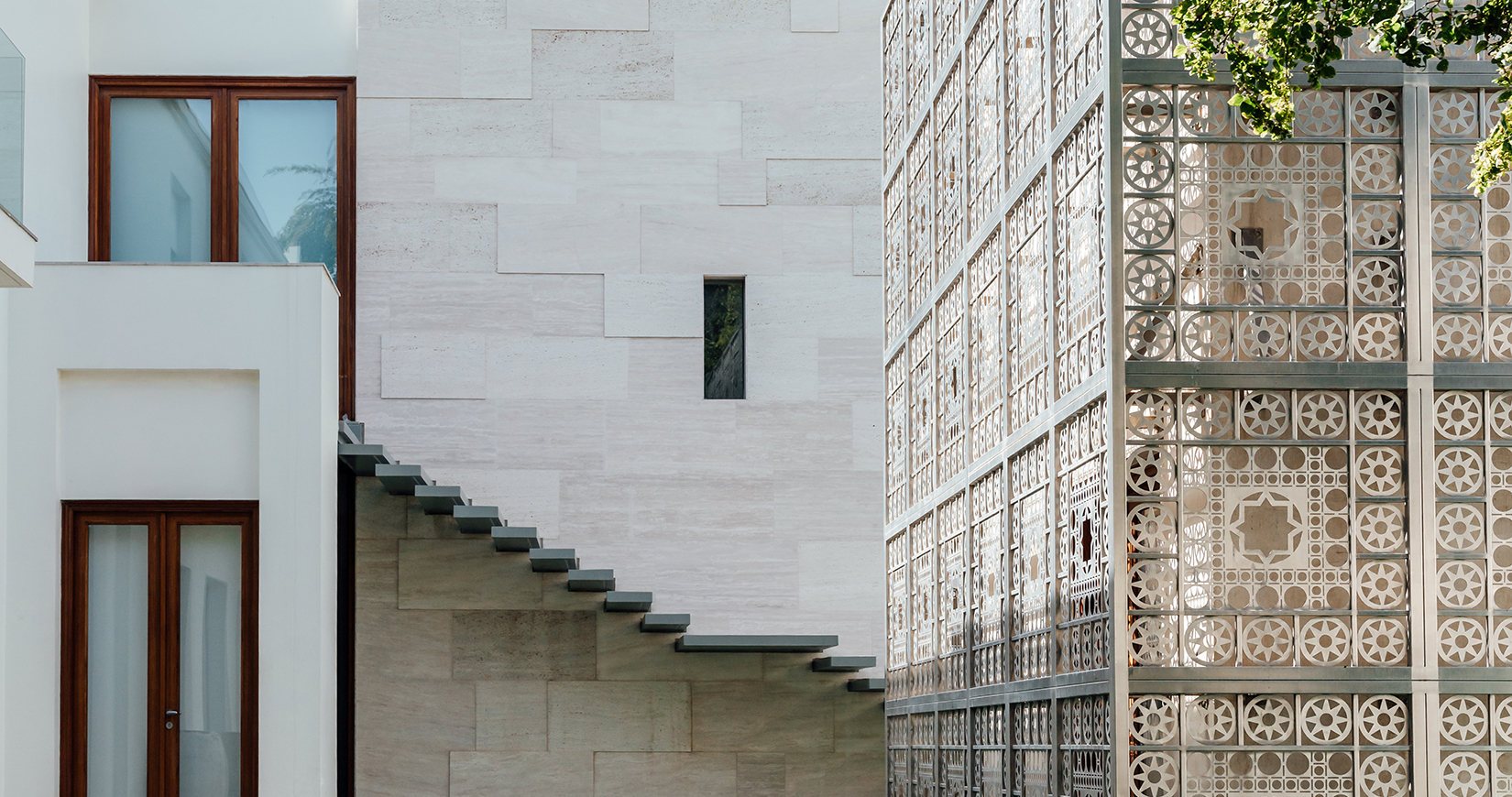

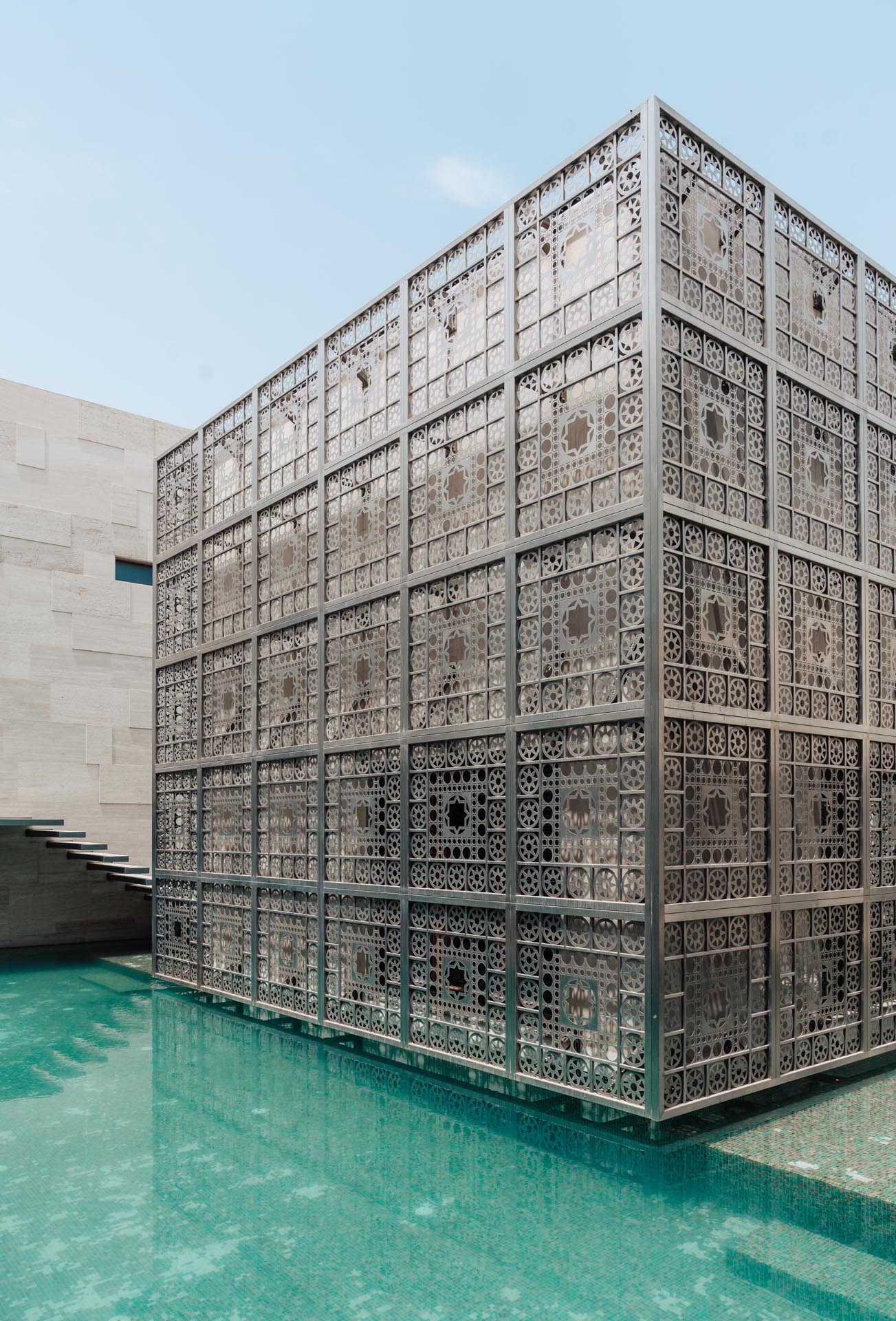

Today, architectural interventions from the 1960s and mid-2010s provide examples of the adaptive re-use of traditional building – a growing field in contemporary architecture. At the building’s entrance, the original gypsum façade was rebuilt with an approach fusing Islamic geometry with contemporary minimalism. Hanging above the traditional wooden door are the edges of a hollow steel cube – a sculpture which also serves as the RAK Art Foundation’s logo.

The 1960s extension, which includes Al Khalifa’s childhood bedroom, was built as Riffa had begun to flourish. “In the ‘40s and ‘50s, modernity started to come in, with electricity and water,” he recounts, recalling seeing a refrigerator for the first time as a child. “I was like ‘wow’. We were really happy drinking cold water. These are good memories; [they make] you appreciate what you have now.”

In 2014, after acquiring the house from his family, Al Khalifa restored and expanded the building in collaboration with the Italian architect Davide Chiaverini. This included a two-storey pavilion in the courtyard, with outer walls composed of steel mashrabiya panels. One of the courtyard walls has been rebuilt with a relief surface of smooth concrete slabs and floatings stairs.

Inside, the Foundation’s look and feel is that of a private residence, rather than a traditional museum, where sculptural works and paintings are peppered amidst modern furniture. “The building was not purposely built for displaying artworks,” Al Khalifa explains.

His collection comprises a global range of modern and contemporary works, including pieces by French painter Pierre Soulages, British contemporary artist Damien Hirst and Colombian sculptor Fernando Botero. It also highlights Al Khalifa’s support of pioneering regional artists, including Moroccan artist Mohammed Melehi and Syrian painter Fateh Al Moudarres.

The artist’s own work, which spans five decades, has evolved from traditional landscape painting on canvas to abstract pieces using a range of materials. The first artworks he remembers admiring were by the 18th-century Venetian painter Canaletto, after receiving a book of the artist’s work from his school’s art prize.

When he travelled to London as an art student in the 1970s, he headed to the Tate Gallery, to view its collection of paintings by British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner. “I said ‘Oh my God, I’m standing here, in front of the real works’,” he recalls. “Turner’s atmospheric paintings of the fog and rain reminded me of Riffa, which has a lot of dust.”

Today, Khalifa works with conical aluminium surfaces to create ambient abstract works. The intersections of design, architecture and art are clear in these works, as is the artist’s interest in spatial structures, light and shadow.

By opening up his home, Al Khalifa’s aim is to support arts education on the island. Historically, Bahrain had a thriving modern art scene, which also served as a base for Iraqi and Palestinian artists in exile.

In the mid-1990s Al Khalifa arranged for the Iraqi painter Rafa al-Nasiri – who was then living as a refugee in Jordan – to teach at the University of Bahrain’s art faculty. “I wanted to enhance the art faculty at the university,” he says.

Al Khalifa, who served as the Bahrain Art Society’s first president, laments the evolution of arts education on the island. “The art scene in Bahrain started earlier [than other parts of the Gulf]. But we should have taken much bigger strides in the last 30 or 40 years,” he says. “One of the reasons is education. We still don’t have an arts college or something similar.”

He hopes that the RAK Art Foundation will help bridge this gap. “It is intended to serve the community, for people to experiment, to enjoy and be inspired,” he says.

The Latest

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.

Asterite by Roula Salamoun

Capturing a moment of natural order, Asterite gathers elemental fragments into a grounded formation.

Maison Aimée Opens Its New Flagship Showroom

The Dubai-based design house opens its new showroom at the Kia building in Al Quoz.

Crafting Heritage: David and Nicolas on Abu Dhabi’s Equestrian Spaces

Inside the philosophy, collaboration, and vision behind the Equestrian Library and Saddle Workshop.

Contemporary Sensibilities, Historical Context

Mario Tsai takes us behind the making of his iconic piece – the Pagoda

Nebras Aljoaib Unveils a Passage Between Light and Stone

Between raw stone and responsive light, Riyadh steps into a space shaped by memory and momentum.