Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

ASA North revitalises old brewery into contemporary art museum in Tehran

Argo Contemporary Museum has been shortlisted for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture

Lovers of Tehran often talk about two parts of the city. Downtown Tehran is known for its markets, university, modernist train station and crowded quarters. Northwards is the more residential uptown with its villas, galleries and boutique hotels, stretching towards the foothills of the Alborz mountains.

But a new contemporary art museum in downtown Tehran hopes to blur this divide. Opened in 2020 by the non-profit Pejman Foundation, which supports art and design in Iran, the Argo Contemporary Art Museum and Cultural Centre is set in an abandoned brewery in the city’s old industrial quarter. It is the first private contemporary art museum to have opened in Tehran since the Revolution in 1979.

“In the past 40 years, the general trend of the city was to move uptown to the foothills. Most of the city’s cultural activity followed that same trend,” says architect Ahmadreza Schricker, founder of architecture practice Ahmadreza Schricker Architecture North in New York, who designed the museum’s modern extension and restoration. The US-based practice Hobgood Architects was also involved in the initial concept phase.

Today, the museum is surrounded by a cluster of galleries and creative studios. “The museum has been cited as a catalyst for the renovation of neighbouring structures, spurring revitalisation in downtown Tehran by attracting artists and galleries,” adds Schricker. It houses the Pejman Foundation’s permanent art collection and includes six gallery spaces, a library, private studio apartments, offices and event spaces.

The Argo factory was originally built in 1921 and was converted into a brewery in 1930. “It was not the most remarkable of buildings, with many industrial architectural twins around the world,” says Schricker of the brick and steel building, “but from a nostalgic point of view, it [has] had a significant place in the local community’s heart and remains the only industrial factory in the city centre.”

After the brewery shut down in 1970, the building was abandoned for over 50 years. “The factory was roofless and in an untamed state,” Schricker shares. “The roof material was stripped away by neighbours and its metal beams carried off by others.”

Today, thanks to Schricker’s design intervention, five concrete prism-like structures serve as a floating roof above the building. Schricker likens it to the roofs of the historic Tehran Bazaar. “The new floating concrete roof plays multiple roles: as a deep skylight it keeps the heat out while filtering the light in for the galleries. It also dances with the neighbouring halabi roofs of downtown Tehran,” he says.

Inside, natural daylight pours in from the ceiling onto the gallery spaces and a large concrete stairwell. The spacious interiors and high ceilings of up to 11 metres give artists more opportunities to play with space. An observation deck for VIPs gives panoramic views over Tehran.

A public courtyard serving non-alcoholic beer allows for the museum’s cultural programme to spill into the city’s streets. “Artists, normal people from the street, art aficionados, city officials, ambassadors from nearby embassies, antique sellers from Manouchehri Street, extras from Arbab Jamshid Street film studios and local tailors all come in to enjoy a pint of re-issued Argo draught beer,” Schricker shares.

Among the areas that required extensive restoration, the new brickwork features a recessed mortar that distinguishes it from the original walls. “The subtle difference between the old and the new mortar [is that it] casts a slightly deeper shadow on the restored areas, distinguishing and showcasing generations of brickwork,” Schricker explains.

This approach contrasts with the other museum building projects in neighbouring countries, such as Jean Nouvel’s Louvre Abu Dhabi or Zaha Hadid’s design for the Heydar Aliyev Centre in Azerbaijan. “We live in a time where the architecture of contemporary art museums is spectacular, so it was interesting for us to convert a modest industrial beer factory in the heart of the capital,” says Schricker. “The architectural response to the history of Argo maintains a restrained conversation between the old and the new.”

This example of adaptive reuse is marked by the economic and political challenges facing Iran. “During this time, the project was influenced by many of Iran’s economic and political realities: an inhospitable socio-political climate, brutal sanctions, a travel ban, a plummeting rial and the isolating experience of the pandemic,” Schricker comments.

To bypass this, the architect made of use of locally available skills and resources. “Everything in Argo was made by hand in Iran, and mostly in Tehran, typically on-site. It was the only way to realise the project,” adds Schricker. “We used regional resources, local materials and native craftsmen, and made on-site decisions.”

In addition, the architect had not lived in Iran for 25 years. “I had never worked in Iran [so] I had to re-learn the local cultural nuances and basic architectural codes. For this I moved to Tehran and lived on-site,” he says.

Yet it is these same constraints that have contributed to the building’s elegance and sustainable design. For Schricker, it is as if these challenges were embedded into the design. “Reality makes design better,” he says.

The Latest

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

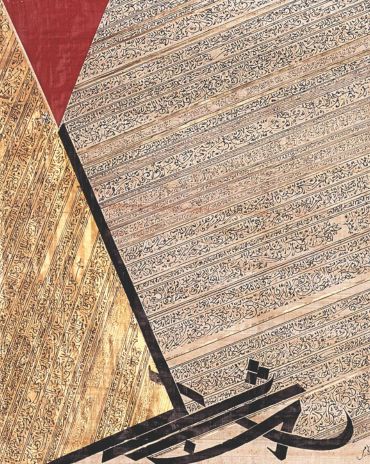

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.