Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Studio Lél is a creative collective in Pakistan at the crossroads of fine art, design and craft reinventing ancient techniques

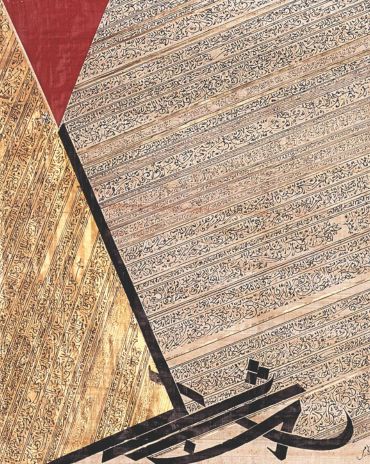

The creative collective creates objects that reinvent the ancient technique of handcrafted stone inlay

Few people outside of Pakistan may have heard about its city of Peshawar – which is located close to the Afghanistan border. However, in the opinion of architect and artist Meherunnisa Asad, the artistic director of collective Studio Lél, Peshawar should be considered a cultural hub.

“There are still many misconceptions about Pakistan in the West,” she begins. “Many people have a distorted perspective of the country because of what they see in the news. Peshawar is one of the oldest living cities in South Asia, with a walled city that is remarkably well preserved.”

It is there – in the sixth most populous city of the country – that Studio Lél has its workshop. Everything started around 30 years ago, when the founder of the collective, Farhana Asad (Meherunnisa’s mother), came across a box in a bazaar in northern Pakistan that was adorned with inlaid stonework. When Farhana found the Afghan craftsman who had made this piece, she asked him to give her lessons. This collaboration between artisans who have mastered old techniques and people escaping the war in Afghanistan is key for Studio Lél today.

“When refugees cross borders, they bring tangible and intangible parts of their culture with them,” says Meherunnisa, who graduated from the National College of Arts, Lahore and Pratt Institute in New York City. She has worked as lead conservation architect at the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme on the conservation of the Lahore Walled City project before joining Studio Lél. “Making becomes part of the healing mechanism – a belief in something that is greater than, and beyond, the region’s sustained conflict and migration. I believe craft has the power to reconstruct identity.”

At the heart of Studio Lél is the art of pietra dura, which dates back to the Roman opus sectile technique that reached its peak during the Italian Renaissance in the 16th century. Consisting of the cutting and fitting of stones into intricate forms, it was considered similar to painting in stone and soon found echoes in Iran, Russia, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan and other countries throughout South Asia. At Lél, this art form now also incorporates other techniques such as French verre églomisé (glass gilding), Chinese cloisonné (enamelling), Italian scagliola and epoxy resins, resulting in one-of-kind furniture and decorative objects. From onyx, jasper, amazonite, agate, jade, serpentine and sandstone to coloured marble sourced from the mountains of Pakistan, lapis lazuli from the Badakhshan province in Afghanistan, malachite from South Africa and turquoise from Iran, a variety of gems and semi-precious stones adorn Studio Lél creations, offering a vast array of colours to create an infinite number of motifs.

For Meherunnisa, telling the stories of the artisans who created these pieces is just as important as preserving their savoir-faire. In addition to promoting the traditional crafts of her country, she also strives to offer a reinterpretation of it, to make it accessible to an international audience. This approach has proven to be successful, with the growing recognition of Studio Lél beyond the borders of Pakistan over the past few years. It’s collaborations with designers and initiatives across the globe – such its recent work with Nada Debs and its collection with Sharjah-based platform, Irthi – has helped spread its message beyond its national borders.

“Through my practice, I seek to draw the world’s attention to Peshawar’s layered history, its importance in the region and the fine craftsmanship that has existed and flourished here for centuries – encouraging new perspectives of Peshawar within its citizens and abroad,” Meherunnisa concludes.

The Latest

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.