Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

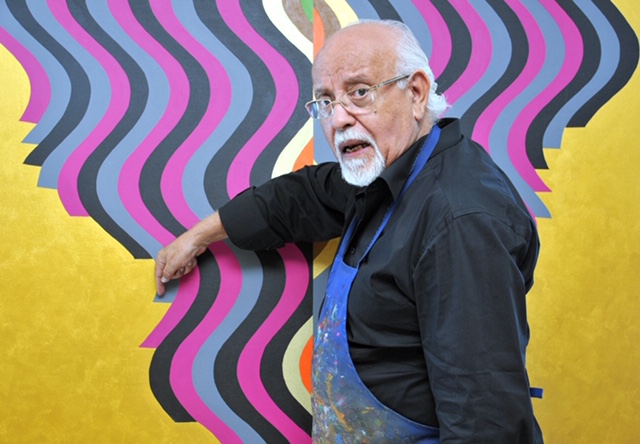

Moroccan artist Mohamed Melehi on the role of colour, the Bauhaus and Afro-Arab heritage

A solo exhibition featuring Mohammed Melehi's works will be on show at Alserkal Avenue on September 19

Born in 1936 in Asilah, Morocco, Mohamed Melehi is regarded as a major figure in postcolonial Moroccan art, and within the history of transnational modernism. He now lives and works between Tangiers and Marrakesh.

Melehi’s art offers a sense of spirit of the aesthetic revolution and exhilaration of post-Independence Morocco. The retrospective exhibition, which opens in Concrete on 19 September, reflects the artist’s creative energy and visual innovation through a unique selection of key works, dating from the 1950s to the 1980s. It also tells the story of the Casablanca Art School during its most radical period, when Melehi taught there between 1964-1969.

Your work is characteristically vibrant — what role does colour play in your distinctive visual language?

My relationship with colour has gone through different stages. Back in the 1950s, during my time as a student at the fine art academies of Western capitals, and in the 1960s, when my attention was captured by Oriental philosophy — specifically Zen and Buddhism — my palette was generally black and white. I wanted to reach a certain peak in minimalism and spatial contrasts. This phase is a lesser-known period in my practice, as audiences generally know me through my colourful compositions.

When I moved to the USA in the early 1960s, I felt an urgent need to use more colour in expressive terms — for instance, the Solar Nostalgia painting from 1962, which shows a more energetic, rather than formalist, use of colour. It soon felt like an explosion of colours happening all at once in a variety of tones and contrasts, hectically guided by this balance between the expressive and the minimalistic impulses for colour. This need became even stronger when I returned to Morocco in 1964.

Untitled, 1970-1971, cellulose paint on wood. Private collection.

In a way, my colourful works show compositions more concerned with attracting concentration, rather than producing distractions. Also, I see colour as a way to attain a certain state of freedom —from materialistic grounds, and from previously held beliefs.

Your sculptural work is inspired by the Bauhaus philosophy that art, architecture and design should be part of every aspect of daily life. Can you expand on this philosophy, and how it applies to your practice, and to your life?

My interest in Bauhaus was particularly driven by the almost existential question of the origins of modernity; the thrill to discover whether a local or non-Western source of abstraction or radical visual language could be compared to movements, such as constructivism, De Stijl, or the Bauhaus.

The parallels became all the more interesting as I went along. We began, with the Casablanca Art School group, to document our own radical modernity from 1965. This was found to be expressed through popular art-making in Afro-Berber crafts (jewels, tapestry, tattoos, etc). Though originating in the 12th century, this iconography (mainly Amazigh signs and symbols) continues to circulate today, and can be found on Saharan roads, all the way through Mauritania, Mali, and further.

Untitled, 1975, Cellulose paint on wood, Private collection.

Eventually, resorting to the Bauhaus was crucial to understanding our own visual roots, which were discovered mostly in our everyday environment. The true sources of local crafts, even when they are forgotten or overshadowed, can resurface through genuine cultural discourse or performance. The Bauhaus encounter represented a paradoxical confirmation that each cultural group or society has a means to express itself genuinely – even in modern terms.

Another specificity of our cultural roots (Arab, African, and Islamic) is the intense link between architecture and calligraphy, as writing expands through space, and vice-versa. These are all the cultural lessons I learned on the ground, but also from the Western movements mentioned earlier, which on the one hand drew inspiration from Arab and African heritage, and on the other hand, inspired us to experiment with new theories, and break away from conservative attitudes.

Vertical, 1960, Acrylic on canvas, Private collection.

You bridge European 20th century graphic sensibilities such as De Stijl and Constructivism with a flowing visual freedom. Tell us more about Mohamed Melehi, the graphic designer. And what does Shoof publishing house do today?

My return to Morocco in 1964 was not without nostalgia for New York City. Casablanca was more attractive to me than Tetouan (where I had graduated from the Ecole des Beaux Arts) and reminded me somehow of NYC and its metropolitan energy. The emerging mass housing buildings, universities, and urban infrastructure in Casablanca couldn’t compare to the heights of American skyscrapers, but the city was definitely on the cusp of becoming a new art capital. Fortunately, this came right on time with my involvement as a professor at the Casablanca Art School.

When I left the school to pursue my own activities in 1969, I established Shoof Publishing. It was the urban development and economic growth taking place in Casablanca that allowed for such a platform — which brought together visual and communication services such as advertising, logo and graphic design, and also book publishing and film editing — to be created and sustained. But it only lasted a little over a decade, as Shoof was stopped at the beginning of the 1980s.

You co-founded the Asilah Arts Festival in 1978, which continues today. What was its purpose then, and how has it evolved since?

When Mohamed Benaissa and I co-founded the Asilah Arts Festival in 1978, Asilah was home to around 30,000 people. The whole idea to begin organising mural art on the walls of the city was a way to stop people from littering on the streets and polluting the city. It was a way to raise social consciousness, and to build a community, with a pedagogical aim. The women and children of Asilah would be invited to paint murals and would attend workshops throughout the festival. Year after year, the festival grew, and our aim to create a sustainable platform and support for social education and active civic citizenship became increasingly significant.

How would you describe the local visual culture of Morocco today, versus four decades ago?

Retrospectively, it seems we have helped bring forward new cultural patterns, but somehow outdated in the Internet era. Nowadays, we experience new behaviours and situations in which mural art and urban experiments can still inspire us. But the whole idea of public space and community-creation have radically evolved into virtual spaces and big data. I personally tend to retire from this noise, to concentrate on my artistic work.

New Waves: Mohamed Melehi and the Casablanca Art School Archives is presented by Alserkal Arts Foundation, and opens in Concrete, Alserkal Avenue, on 19 September, and runs until 10 October. It is curated by Morad Montazami and Madeleine de Colnet of Zamân Books & Curating.

Explore a preview of the exhibition, including interviews with curator Morad Montazami, on alserkal.online

The Latest

Dubai Design Week 2025 Unfolds: A Living Celebration of Design, Culture, and Collaboration

The 11th edition of the region’s leading design festival unfolds at Dubai Design District (d3)

Preciosa Lighting Unveils ‘Drifting Lights’ at Downtown Design 2025

The brand debuts its newest 'Signature Design' that explores light suspended in motion

IF Hub Opens in Umm Suqeim

A New Destination for Design and Collaboration in Dubai

The Language of Weave

Nodo Italia at Casamia brings poetry to life

The Art of the Outdoors

The Edra Standard Outdoor sofa redefines outdoor living through design that feels, connects and endures

The Art of Wellness

Technogym collaborates with Assouline to release a book that celebrates the brand’s 30-year contribution to the fitness industry

The Destination for Inspired Living – Modora Home

Five reasons why you need to visit the latest homegrown addition to the UAE’s interiors landscape

Elemental Balance — A Story Told Through Surfaces

This year at Downtown Design 2025, ClayArk invites visitors to step into a world where design finds its rhythm in nature’s quiet harmony.

The identity Insider’s Guide to Downtown Design 2025

With the fair around the corner, here’s an exciting guide for the debuts and exhibits that you shouldn’t miss

A Striking Entrance

The Oikos Synua door with its backlit onyx finish makes a great impression at this home in Kuwait.

Marvel T – The latest launch by Atlas Concorde

Atlas Concorde launches Marvel T, a new interpretation of travertine in collaboration with HBA.

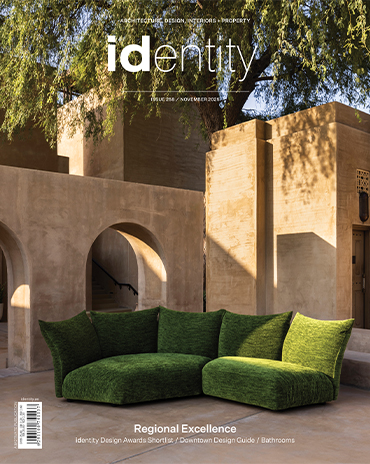

Read ‘Regional Excellence’ – Note from the editor

Read the magazine on issuu or grab it off newsstands now.