Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Anne Holtrop discusses his unconventional approach to creating architecture

Bahraini architect Batool Alshaikh interviews Anne Holtrop about his architectural process

It is difficult to place the work of Dutch architect Anne Holtrop within the category of traditional architecture. For one, his process is closer to that of a sculptor working directly with material and form, exploring their properties and experimenting with processes. Holtrop’s use of material not only builds but also shades and highlights, in the way an artist would with a sharpened pencil. His architecture is more fragments than wholeness, influenced by various production methods – the ‘making of’ is equally if not more important than the final form – be it simple concrete casting, hand-cutting stone or casting reliefs. Holtrop has developed a new form of desert architecture that merges with its material surroundings, while the term ‘contextual’ sits on the edge

Introduction by Aidan Imanova

When I was asked to interview Anne Holtrop, I immediately thought that in a way, it might be possible for me to write a detailed text on his work without the need to spend an hour asking him questions. I have been witnessing the studio’s work very closely for the past six years, not only because of my role at the architecture department of the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities – which acts as a client for some of Holtrop’s projects – or because I pass multiple buildings by the studio every day on my way to work; or even because many people within my close circle used to, or still do, work at the studio, or because we actually work in the same building in Muharraq. I think it is mostly because the carefully crafted work of Studio Anne Holtrop demands to be noticed, experienced and admired.

Holtrop often mentions in interviews that he always wanted to be an artist rather than an architect. His architecture practice started as a self-imposed initiative, encouraged by a piece of advice that was given to him by the Dutch artist Krijn de Koning, whom Holtrop had spent some time assisting before starting out on his own. de Koning once told him that “being an artist is that no-one is asking for your work”.

“Around that moment, I got an open-ended invitation to take part in the SITE2F7 exhibition for the Museum De Paviljoens – there was this land behind the institute for proposed work,” he shares. “It was very difficult for me to understand what I wanted to propose but [I] had to go with what I was most familiar with, and that was architecture. I proposed to make the trail house [although] no-one really asked for a house. That helped me understand that I can be an architect and still work with a certain autonomy.”

Holtrop’s body of work is motivated by making, a research process which he calls “material gesture” and fundamentally involves experimenting with materials and methods of production. His studio, located in a typical heritage courtyard house in Muharraq, somewhat resembles an exhibition space. The central courtyard is ever-developing, featuring ambitious large-scale models that are architecture within themselves and which are often produced using the same methods that are used to build the final structures, in order to understand the process of construction – a smaller-scale mock-up of sorts.

Holtrop’s work is always presented with the documentation of the material and production process, as well as images of models, images of places of production, drawings and site documentation.

“I think we show the process because we want to show the engagement that is the journey itself. And that journey is inclusive of many people that work and contribute to the project. The process gives a notion for an understanding of the place,” Holtrop explains. “I find it interesting to see something as a process and not only as some kind of fixed ends.”

While the work itself often appears to be accidental or ‘by chance’, most of these chances are, in fact, calculated and studied with a preconceived idea of the outcome. Holtrop describes it as throwing paint on the wall and creating a splash: when done 100 or 1000 times, the outcome is somewhat known but still expected to include a certain level of ‘newness’.

“The work deliberately does not want to be defined or too precise; it is more of a step-by-step process,” Holtrop says. “This is not only in the design phase – we also bring it to the construction site. We allow for the outcome to have a certain possibility for variations. With that ambition, the process allows [for] being more inclusive for other agendas that raise important questions – for example the sourcing of materials, environmental issues, issues of locality, or if this place has a specific meaning in making this project. So, these are agendas that can be addressed. I think if you keep too much just within the design or within the studio, the outcome can be very closed-off.”

Within the many works of the studio, one can observe a thread of themes – or ‘series’, as Holtrop calls them. Be it freeform drawing, cutting or casting, the varying approaches all fit within the wider theme of material exploration that is inherently central to his work. While the approaches may vary, the process always remains intact. One may observe these categories as specific chapters that Holtrop closes and moves on from, but the reality proves that he is a lot more fluid with the process – always going back and forth, always returning and adjusting. We can see the free drawing in the trail house project, the cuts of the Bahrain Pavilion and Murad House, and his furniture designs and the casting in Batra, Green Corner and Qayssariyah Souq, in addition to other approaches that are all part of his process of actively working with materials and building techniques.

“The nice thing about making more work is that it starts to become a mass of work. There is a critical weight in continuing to find ways of escaping it, but not destroying what you have achieved. They are different approaches, but they all deal with the same topics in a way; the same interests. The challenge is that we don’t want to make the next Green Corner building or the next Souq because that is not interesting. The interesting part is to know how to use that as a critique, [and] to be able to escape it by producing something new.”

Throughout Holtrop’s practice, the studio has dabbled between a variety of endeavours, from furniture to installation to pavilions, to commercial spaces, to permanent structures. However, Holtrop’s approach to arriving at any project is always the same: it is always architecture, but the scale differs. The studio is currently working on creating cosmetic bottles for a brand, the first time that it was possible for Holtrop to see the final scale of a project in its design phase.

“I think when the work is temporary – for example, an exhibition – you can take more risks. But I also take a lot of risks in the building,” Holtrop confides. “And we often have situations where we are at the border of experimentation failure; but in these cases we try very well to control our experiments. And we try to get the best people on board to help. But there’s always the chance that what you do is just not going to work.”

Even though, since the start of his practice, Holtrop’s projects have been situated within domains of culture and the arts, he is open to different types of projects that may spark his curiosity. When I suggested that perhaps social housing could be an interesting next step, Holtrop responded that he agrees but it might not be within the core of his work currently, that commissioners often go to architects with a certain level of experience in a subject, which can sometimes get tricky when, for once, you take on a project in an entirely different sector. The studio is currently working on its largest project to date: an art institute in Riyadh.

“When I get asked the question ‘What would be your ideal next project?’ I have no clue. But if someone comes with an interesting question, or let’s say an engagement with something that I think I can work with, that would be nice too. It is not always about the topic, but the conditions as well.”

Holtrop’s works often have an atmospheric quality to them, one that is not necessarily attached to its context but somehow creates a context within itself. In the case of the recently-completed Green Corner building in Muharraq, the building does not respond to the site contextually, but has a more metaphorical response which sees its walls and ceilings as cast elements on sand reliefs from the site itself in Holtrop’s “imaginary landscape”.

“It is how to condition your interest… A drawing doesn’t depict anything, but it is the projection of our imagination; that [is when] we start seeing something.”

Holtrop confesses that his relationship with his completed work is quite an awkward one and charged with self-criticism; always questioning whether the work is in its best form and whether what is produced represents the best possibility of an idea. Because of that, Holtrop has started photographing his own work, in an attempt of continue its process and not reach the endpoint just yet.

“… that way I’m still able to continue to work on it, to get an understanding of it, to read it, to literally frame [it],” Holtrop explains.

The Latest

How Eywa’s design execution is both challenging and exceptional

Mihir Sanganee, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder at Designsmith shares the journey behind shaping the interior fitout of this regenerative design project

Design Take: MEI by 4SPACE

Where heritage meets modern design.

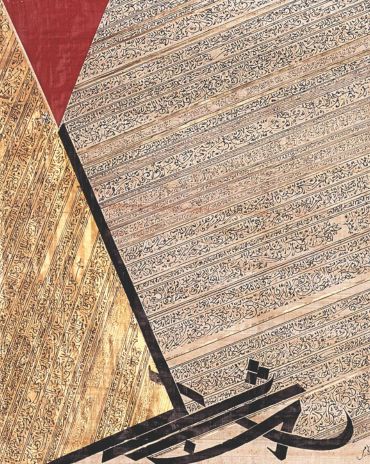

The Choreographer of Letters

Taking place at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation until 25 January 2026, this landmark exhibition features Nja Mahdaoui, one of the most influential figures in Arab modern art

A Home Away from Home

This home, designed by Blush International at the Atlantis The Royal Residences, perfectly balances practicality and beauty

Design Take: China Tang Dubai

Heritage aesthetics redefined through scale, texture, and vision.

Dubai Design Week: A Retrospective

The identity team were actively involved in Dubai Design Week and Downtown Design, capturing collaborations and taking part in key dialogues with the industry. Here’s an overview.

Highlights of Cairo Design Week 2025

Art, architecture, and culture shaped up this year's Cairo Design Week.

A Modern Haven

Sophie Paterson Interiors brings a refined, contemporary sensibility to a family home in Oman, blending soft luxury with subtle nods to local heritage

Past Reveals Future

Maison&Objet Paris returns from 15 to 19 January 2026 under the banner of excellence and savoir-faire

Sensory Design

Designed by Wangan Studio, this avant-garde space, dedicated to care, feels like a contemporary art gallery

Winner’s Panel with IF Hub

identity gathered for a conversation on 'The Art of Design - Curation and Storytelling'.

Building Spaces That Endure

identity hosted a panel in collaboration with GROHE.